Why Hasn’t Congress Authorized Force Against ISIS?

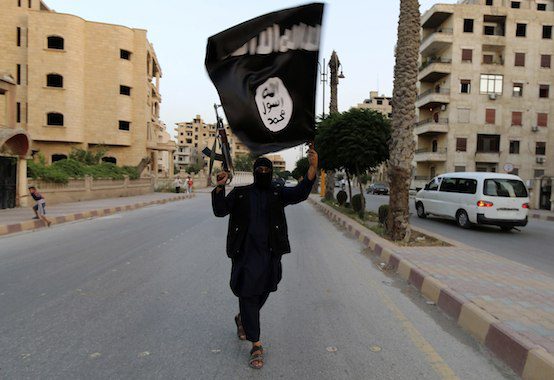

This coming August, the United States will have been engaged in a war against the Islamic State for two years. Tens of thousands of U.S. airstrikes on ISIS targets will have been conducted, billions of dollars will have been spent, and several thousand advisers and special-operations forces will have been sent to Iraq and Syria to gather intelligence, train local forces, and prepare plans for the final thrust into the cities of Mosul and Raqqa.

All of this will have happened without the U.S. Congress performing its most important job under the Constitution: declaring war or passing an authorization for the use of military force. In a new lawsuit, one professor, one human rights lawyer, and a captain in the U.S. Army aim to force the issue.

“The Congress,” reads Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, “shall have Power … To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water.” And the War Powers Resolution—passed in 1973 over President Richard Nixon’s veto—requires the president to come to Congress for a force authorization or declaration of war within 60 days of introducing U.S. troops into hostilities. If the president fails to come to Congress or fails to receive that authorization, U.S. troops are required to redeploy out of the conflict zone within 30 days.

In short, while the president may be commander-in-chief, Congress has the power not only to fund a war, but also to approve it in the first place. Yet these laws have largely been ignored by the Senate and House leadership, and Congress remains unable to come to a compromise on how much war authority it should grant the White House.

As a result, President Obama has relied on the 2001 and 2002 War on Terror authorizations as legal justification for the current conflict in Iraq, Syria, and increasingly Libya. The 2001 resolution authorized force against the individuals and groups who “planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001”; the next year’s allowed the president to address “the continuing threat posed by Iraq.”

The new lawsuit requests a ruling that President Obama violated the War Powers Resolution, and that the White House should request congressional authorization for the war within 60 days of the judgment. And Capt. Nathan Michael Smith, the man who filed it, is no anti-war activist. In fact, he not only supports the war against ISIS but believes that the United States possesses a moral duty to lead the international community in destroying what he describes as an “army of butchers.”

Smith, however, is incredibly distressed that the war is technically illegal: “How could I honor my oath when I am fighting a war, even a good war, that the Constitution does not allow, or Congress has not approved?” he asks in the declaration he attached to the suit.

This is precisely the question that Bruce Ackerman, the Yale University law professor acting as a consultant in the lawsuit, has spent so much of his career trying to answer. Ackerman has long been the principal crusader for a new authorization of military force—partly to get the legislative branch back in the game, and partly to restrain an executive branch that he argues is running far beyond what the Constitution allows. His most passionate attack on President Obama occurred in the op-ed pages of the New York Times even before the first U.S. bombs were dropped in Syria. “Mr. Obama may rightly be frustrated by gridlock in Washington,” Ackerman wrote, “but his assault on the rule of law is a devastating setback for our constitutional order. His refusal even to ask the Justice Department to provide a formal legal pretext for the war on ISIS is astonishing.”

Some doubt the suit will get far. “This case presents a unique opportunity for the federal courts to pass upon just how broadly the president can construe a use-of-force authorization,” Steve Vladeck, a professor at American University’s Washington College of Law and editor-in-chief of the popular law blog Just Security, told me. “Unfortunately, it’s not at all clear that the courts will get to answer that question.”

For example, instead of considering the merits of the case, a court could find that Smith lacks standing to sue. And if the court fails to consider Captain Smith’s suit, the AUMF debate will likely remain in limbo for the rest of President Obama’s term.

None of this, of course, would be an issue if Congress had the political courage to engage in a real, public debate about the war on ISIS on the House and Senate floor. But this appears to be too much to ask from America’s elected representatives; indeed, the furthest members of Congress have gotten is debating whether the 2001 AUMF should be rescinded. Republicans and Democrats are still fighting amongst themselves about how many U.S. troops should be deployed, which countries with an ISIS presence should be bombed, and how long the bombing should last. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has demonstrated no interest in resurrecting a debate about war during a presidential-election year, despite the fact that this is exactly what the Republic’s Founders would have expected.

The American people deserve better from their elected representatives. And so do the troops in the ground and the pilots in the air who are in the middle of a war zone.

Daniel R. DePetris is an analyst at Wikistrat, Inc., a geostrategic consulting firm and a freelance researcher. He has also written for CNN.com, Small Wars Journal, and the Diplomat.

Comments