The Populist Patriotism of Gore Vidal

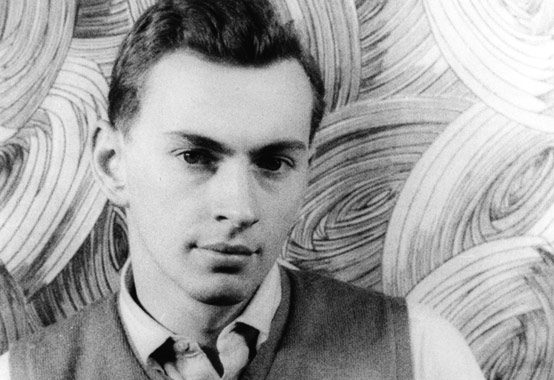

“Contrary to legend,” writes Gore Vidal in Point to Point Navigation, the second (and presumably final) volume of his memoirs, “I was born of mortal woman.” He passed into this world in the Cadet Hospital at West Point, an institution he would later write about with the keenest insight and even affection. (As a boy he loved to play with toy lead soldiers, though “Today they would be proscribed because war is bad and women under-represented in their ranks.”)

The century into which Gore Vidal was born—which modest Yankees would not think of calling the American Century; that would be the conceit of the silly son of Chinese missionaries—had reached the quarter pole. Mr. Wilson’s unsuccessful attempt to remould America into a militarized police state was a queer and fading memory. Normalcy was upon the land. Genius, too. Writes Vidal: “In 1925, the year that I was born, An American Tragedy, Arrowsmith, Manhattan Transfer, and The Great Gatsby were published. A nice welcoming gift, I observed to the Three Wise Men from PEN who attended me in my cradle.”

The boy’s father, Gene Vidal, former West Point fullback and Olympic decathlete, taught aeronautics at the U.S. Military Academy and later helped found the airline that would become TWA. Gene seems to have been a bit of dreamer; he was convinced that before too many years every American would have his own airplane. If, instead, every American male wound up with Social Security and draft cards, well, you can’t blame a guy for his reveries. Gene may or may not have had a fling with aviatrix (a now verboten word!) Amelia Earhart, but Gore is not about to fault his father for infidelity. “The serenity of [Gene’s] nature,” says his son, “was in benign contrast to my mother’s raging nature.”

Nina Vidal was “a composite of Bette Davis and Joan Crawford,” a kind of Mommie Dearest who married the main chance, in her case the moneybags Hugh D. Auchincloss, thus making Gore Vidal a stepbrother to the future Jackie Kennedy Onassis through a concatenation of upper-class remarriages. Vidal draws the appropriate lesson: “Oh, what a tangled web is woven when divorcees conceive.”

One might not associate Gore Vidal with “family values,” even had that phrase not become a cynical advertising slogan exploited by adulterous Republicans, but in fact family has often been his concern. He writes here, as he has so often before, about his father and his maternal grandfather, the blind Oklahoma Senator Thomas P. Gore, with a filial reverence. These were the men he took for his models. They served him well, if uncommonly.

And of course the country itself constitutes Vidal’s extended family, or at least it did. Though Vidal is beyond question one of the finest essayists ever to use the language, his greatest achievement may be his “Narratives of Empire,” the septology of historical novels which covers the rise of the American Republic and its tragic, enraging fall (felled, as it happens, by the American Empire). His subject is “the Republic’s history, which I have always regarded as a family affair.” He is the nation’s biographer, which is why those who would efface our history or deny that anything much happened prior to 1941 detest Vidal. A patriot, he is called anti-American by those who can’t be bothered to find out what was going on in the crazy old America before the advent of atomic bombs, McGeorge Bundy, and the films of Tony Curtis.

Senator Gore, to whom the young Vidal read the Congressional Record, impressed upon the boy that the populists, however maligned by the establishment, kept alive the spirit of ‘76. Of his grandfather, an ally of Bryan and enemy of Wilson and FDR, Vidal writes, “He was a genuine populist; but he did not like people very much. He always said no to anyone who wanted government aid.” (Equal rights for all, special privileges for none, as the populist motto went.) Senator Gore, says his grandson, was “the first and, I believe, last senator from an oil state to die without a fortune.”

Senator Gore was one of the earliest and most vigorous sponsors of a constitutional amendment to require a popular referendum on any congressional declaration of war. The boy Vidal saw firsthand just how hard the whip comes down on men who take a stand for peace. “[P]opulists,” he learned, “have never had a good press in Freedom’s land.” Herein, as in previous books, Vidal defends the America First Committee and his childhood hero Charles Lindbergh against the slanders of the War Party.

He entertainingly depicts Huey Long, the good-humored antimilitarist whose death at the hands of the soon-to-be-cliched lone nut removed a formidable challenger from FDR’s path to perpetual presidenthood. Huey lived in the same Connecticut Avenue apartment building as did Gene Vidal, and Gore’s father recounted Long’s lectures to a meek young desk clerk: “Why, when I was your age I would spend what little idle time I had with an instructive book not that racing form I see that you’re now trying to hide. Of course I was not given to late-night dissipation in the fleshpots of the District of Columbia! Oh, you can’t hide your ruinous habits from me! I can see by the trembling of your hands what demon rum is doing to you…”

Vidal supplies the punchline: “Only my father’s arrival with his car would stop the great flow of language, and Huey would cadge a ride from the director of air commerce while lecturing my father on aviation.”

Vidal wrote about his World War II service in Palimpsest (1995), his previous memoir, and in the decade since he has not joined the Greatest Generation orgy: “during the three years I spent in the army I never heard a single patriotic remark from a fellow soldier, only grief for friends lost and, almost as often, a fierce grievance felt for those back home who were decimating our adolescent generation.” Cue a Brokavian sigh.

Grief for friends lost. This is the presiding mood of Point to Point Navigation. The book is about death; almost all of its personae (Tennessee Williams, Johnny Carson, Saul Bellow, Paul Bowles, Federico Fellini) are on the other side of corporeity. Vidal also writes movingly of Howard Austen, his partner of 53 years, who died of lung cancer in 2003, when “ ‘we’ ceased to be we and became ‘I.’“

As a “third-generation atheist” and “absolute nonbeliever” he takes no solace in the promise of eternal life, though you can’t beat the view from his future resting place: Rock Creek Cemetery in the District of Columbia, hard by Henry and Clover Adams and Saint-Gaudens’s “Grief” statue. “Two or three yards away Howard is buried as I shall be in due course when I take time off from my busy schedule,” he writes. One imagines Vidal and Adams, the two disappointed sons of our disappearing (disappeared?) Republic, trading aperçus unto time’s end. Oh to be a fly on the sepulcher wall in that afterworld!

The author notes his own physical deterioration, though it appears the wit is the last to go. He is, as ever, just plain funny. Here is Vidal on vanity: “Generally, a narcissist is anyone anyone better looking than you are.” And on standing up for the infant son of friends: “Always a godfather, never a god.”

Or here is Vidal on Greta Garbo, whose favorite reading material was Silver Screen: “She kept up with all the new stars though I can’t imagine she saw many of their pictures, but when it came to Fabian’s romantic life she was au courant.”

Vidal turned 81 in October, but he takes no pride in having outlived the subject of his life’s work. “Our old original Republic does seem to be well and truly gone,” he says in a line freighted with sadness. A son, a loving if irreverent son, of that old Republic has watched the precious thing die, and a new entity, bearing the same name, but “more and more secretive and remote not to mention repressive,” supplant it.

“Didn’t it go by awfully fast?” a dying Howard Austen asked Vidal. It sure did.

Gore Vidal is an American original. No, make that an original American. He despises cant, hypocrisy, foreign wars, and martial intellectuals on the make. He cherishes the old American Republic. I laugh aloud reading him. I take heart that he is still out there, an improbable—but, when you think about it, perfectly and delightfully meet—blend of Edmund Wilson and Huey Long, T.P. Gore and Henry Adams.

“As I now move graciously, I hope, toward the door marked Exit,” Vidal begins one sentence. Don’t go yet, Gore. Henry Adams can wait. We American patriots have so much left to do.

__________________________________________

Bill Kauffman’s most recent book is Look Homeward, America: In Search of Reactionary Radicals and Front-Porch Anarchists (ISI Books).

The American Conservative welcomes letters to the editor.

Send letters to: letters@amconmag.com

Comments