The Moral Path to Peace

Humanity faces no greater challenge in the 21st century than averting conflict among peoples and civilizations. It is curious and revealing that experts in international relations and political science generally seem not to be beyond themselves with worry that this century might see the war that will make all previous wars look minor. A deteriorating relationship between China and the United States and more arrogance and obduracy in the Middle East are but the most obvious possible sources of a great conflagration.

Superficiality in defining the dangers or delay in addressing them could have horrendous consequences. Yet discussions of how to minimize conflict typically neglect what may be the most important part of the problem. In the West particularly, it is common to assume that general enlightenment will remove obstacles to peace—this despite the fact that we need only look to the century preceding this one, the most murderous and inhumane in all of history, to recognize that the spread of supposedly sophisticated ideas and science does not reduce the intemperance, belligerence, or cruelty of human beings. It only provides them with new means of asserting their will.

Many in the West expect that certain political and economic arrangements will promote peace—“democracy” and “markets” being perhaps the most popular at the moment. They think that universal suffrage and economic interdependence will be salutary. Many hope that international agreements and increasing the influence of the United Nations will keep the peace. Behind some prescriptions for lessening tension there lingers a sentimental notion of the brotherhood of man. As fellow human beings, can’t we just hug? Meanwhile, those who consider themselves more realistic favor balance-of-power theorizing.

But most attempts to deal with conflict do not deal in any depth with what may be the very core of the problem, man’s moral predicament. Proceeding from a dubious or incomplete understanding of the basic moral terms of human existence, scholars and others exaggerate what elaborate, clever international arrangements or techniques can do to lessen tension. The trouble is that when passions run high even the most efficacious measures can be swept away in the blink of an eye. In fraught, very tense circumstances peace will have a chance only if the actors involved are not only experienced, knowledgeable, and creative, but capable of withstanding, in themselves as well as others, the onrush of rashness, belligerence, and ethnic-nationalistic fervor. Such urges can be tamed in the end only by strong character, including habits of restraint and caution. You want peace? Then you need peaceful individuals.

Yet the subject that may be most important seems largely alien to the Western intellectual elites. I have in mind the moral and cultural preconditions of peace. They are crucial, first, because efforts to avoid conflict are likely to be unsuccessful unless those involved have a certain kind of will and imagination, second, because the relative importance of other aspects of how to deal with conflict are best assessed in light of the most complete view of what makes human beings tick. That the subject of the moral and cultural preconditions of peace receives far less attention than other topics seems a sign that Western intellectuals may not be well equipped to deal with the most pressing problem of the new century. Upbringing and education in the West may have to be significantly revised.

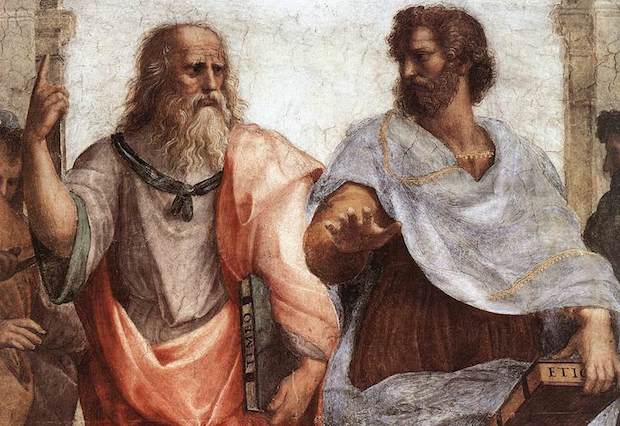

In exploring the issue of morality we must, partly because we find ourselves in a globalizing age, guard against intellectual provincialism, presentism, and other myopia. We need to repair to the historical experience of mankind. We should be willing, at minimum, to question the prevalent view of modern Western intellectuals that moral values are merely “subjective” or that moral beliefs are just the idiosyncratic creatures of historical circumstance. If we think more historically and internationally, a different possibility emerges. Amidst a wide variety of beliefs in the human past and present the open-minded scholar finds what looks like a shared, if variously expressed, sense of higher values, a universal dimension. The ancient Greeks called these values the good, the true, and the beautiful. The great moral and religious systems give primacy to the good, that is, to moral universality. In these traditions ecumenical research finds far-reaching transcultural and transhistorical agreement on what is the central moral problem of human existence: that the human will is cleft between higher and lower potentialities and man is his own worst enemy.

National arrogance and economic ruthlessness are among the obvious and palpable threats to international harmony, but they are but instances of the more general danger that societies and their leaders, instead of interacting on the level of what is morally, aesthetically and intellectually noblest in each, will interact at their worst, when most self-absorbed, grasping, and intense. Enlightened self-interest, as opposed to crude, short-sighted self-interest, can go a long way towards keeping competing parties from clashing, but a mere coincidence of partisan wills provides no stable and lasting basis for peace. That popular Western culture is today spreading around the world creates a commonality of sorts, but it is a fragile, very questionable likemindedness. This popular culture is almost uniformly disdainful of the moral and cultural traditions of mankind, including those of the Western world, and is perceived by many as a threat to their most deeply held beliefs. Because of its crudities and vulgarities it antagonizes rather than appeals to the more discerning and discriminating representatives of the peoples of the world.

No observation would seem to be more richly confirmed by the historical record than that human beings are morally cleft, to the core, between higher and lower potentialities. Yet this crux of the human predicament is strangely denied or ignored in most Western attempts today to find a way to harmonious and just arrangements. One thinks, for example, of the long-influential moral rationalism of a John Rawls, with its propensity for wholly ahistorical ratiocination. The Rawls who was widely celebrated would have human beings step behind “the veil of ignorance” and consider policies without regard to how they might affect them personally. “Reasonableness” would then preside over deliberation, and justice and harmony would be served.

The same fondness for abstract theorizing and reluctance to think historically and concretely marks theories of communicative or deliberative democracy. Sound policy and harmony are expected to emerge from never-ending conversation that excludes no legitimate groups. There is something very abstract and even dream-like about these theories. They assume what must not be assumed, that human beings are interested in listening to competing views. They are not. They want their own way. They think of opposition as annoying and as something to be overcome. What these theorists do not quite realize is that when people do show a genuine willingness to consider the ideas of others, it is because they have learnt to control the passions that would close them down intellectually.

Openness of mind presupposes a special, rather sturdy moral self-discipline and habituation. The framers of the U.S. Constitution set up a system that would encourage debate and compromise. Americans would be governed by their “deliberate sense.” But the framers were acutely aware that for this system to work those active within it would have to be capable of self-restraint and be willing to respect the views of others. Their system had demanding moral and cultural preconditions. A certain character type—I like to call it the “constitutional personality”—had to be available if genuine deliberation were to take place.

More recent theorizing about how to achieve communication and harmony does not explore in depth how to create the moral and cultural conditions favorable to deliberation, dispassionate judgment, and compromise. Exhibiting ahistorical and sentimental leanings, today’s theorists simply assume that when people operate in a more progressive, egalitarian setting they will be spontaneously predisposed to reasonableness and to hearing the arguments of others. This is wishful thinking. Theories of this abstract, rather dreamy type have limited value in discussions of domestic politics, and they are wholly inadequate for international relations. There is need for a more realistic, robust understanding of the real sources of open-mindedness and civilized conduct.

In the end, only moral character, supported by general culture, can fortify the self in man that wants openness to argument and respect for others. It used to be regarded as the central purpose of civilization to assist individuals in reining in their least admirable traits so that more admirable ones could be developed. Only protracted moral and cultural exertions and habituation, encouraged by the surrounding society, bring forth people of this kind. In proportion as the people of a society fall short, they undermine not only their own well-being and the cohesion of their society but also international relations.

Until fairly recently, it was taken for granted by most in the Western world, as it was in the East, that human beings are torn between desires that enhance existence and ones that, though they may bring short-term pleasure, are destructive of a deeper meaning and are potentially diabolical. To realize what the ancient Greeks called eudaimonia, happiness, a person must learn to discipline his appetites of the moment, try to extinguish some of them, with a view to his own enduring higher good. Happiness does not refer to a maximization of pleasure but to the special sense of well-being and self-respect that attends living nobly and responsibly. It is for the sake of this higher life that a person foregoes momentary pleasures and advantages.

The good life has many aspects and prerequisites—moral, intellectual, aesthetic, political, and economic—but there was widespread agreement in the old Western society, whether Greek, Roman, or Christian, that realizing life’s higher potential ultimately depends on the person’s character and quality of will. A person who lacks the strength to act rightly cannot achieve happiness by dint of intellectual brilliance, imaginative power, or economic productivity.

According to the old Western tradition and corresponding traditions in the East, society should encourage the kind of working on self that will build meaning and worth into personal and social existence. Whether the goal is the happiness and nobility of a worldly life of the kind that Aristotle and Confucius advocate or the special peace of holiness in which religion culminates, there is no substitute for the protracted, often difficult effort of will.

Note carefully that the most important measure of progress is the quality of actions performed. “I am the way and the truth and the life,” said Jesus of Nazareth. The statement implies that its validity could be tested only in practical action. In Buddhism, the right Way is the diligent working on self to extinguish needless or destructive desire. In the Dhammapada, which is attributed in its general spirit to the Buddha, we read about the path to Nirvana: “You yourself must make an effort.”

In the West, the most radical and influential challenge to this view of man’s moral predicament came from Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). Rousseau was, among other things, the main intellectual inspiration for the French Jacobins, who spearheaded the French Revolution that started in 1789. For Rousseau, the old view of human nature is profoundly mistaken. Man is not chronically torn between good and evil. There are in man’s own nature no lower inclinations, certainly no original sin, as Christianity alleges. Man was born good. In his primitive, presocial, “natural” state, man was pure, simple, peaceful, and happy, and that remains his nature. The evil in society is due not to some perversity in man but to perverse norms, habits, and institutions. Destroy that society, and man’s goodness will be released.

Rousseau and his many followers pioneered a revolution in the understanding of morality that continues to reverberate. Virtue ceased to be a matter of character and right willing. It became primarily a state of feeling and imagination, an attribute of the “heart.” Rousseau gave prominence to tearful empathy, “pity,” as a sign of human nobility. The old measure of moral virtue was loving, responsible action. Good conduct was the outgrowth of sometimes painful self-scrutiny and a diligent working on self. But for Rousseau man was good by nature, so there was no need for man to be on guard against his own lower impulses. Neither was there any need for traditions, social groups, or institutions to buttress morality. On the contrary, it was by liberating man from such traditional constraints that natural goodness would reassert itself. Rousseau and his followers shifted the central struggle of human existence from the inner life of persons to the social and political arena, where the virtuous had to defeat evil forces.

Rousseau’s redefinition of morality, which by itself had a profound influence in the modern Western world, coincided historically with the kind of rationalism that seized the initiative with the Enlightenment. Its conception of reason was heavily slanted in the direction of mathematics, geometry, and natural science. Representatives of the Enlightenment rejected the traditional view of man as superstitious and unscientific. They had no place for ancient moral wisdom. A happy life was not dependent on moral character but required a fundamental restructuring of society according to enlightened ideas.

Rousseauistic sentimentality and Enlightenment rationalism might seem to be wholly different approaches to life, but they became close and frequent allies. Both belittled the need for moral character. Selfishness, ruthlessness, avarice, and conflict were not due to any chronic human weakness but could be overcome by remaking the social and political exterior. Sentimental idealism and rationalism came together in social engineering, dreamy idealistic visions of the future providing the goal and technocratic manipulation providing the method. In the area of international relations, sentimental virtue and technocratic thinking eventually combined in the idea of an enlightened and vaguely egalitarian global culture, often summarized in the term “democracy.” According to this ideology, the historically evolved characteristics of peoples, societies, and civilizations will soon give way to a proper transnational ideological homogeneity. History will “end.”

This notion of emerging global harmony neglects the central issue of moral character. Equally troublesome is the presumption that persons, societies, and civilizations should give up their traditional distinctiveness. Let me suggest, to the contrary, that what might actually be the most conducive to cordial relations is to cherish—not disdain—historically evolved identities, though to cherish them in a particular manner. It is not contradictory or even paradoxical to view this respect for historical particularity as a kind of cosmopolitanism. It is a cosmopolitanism that would encourage particular persons, societies, and civilizations to be themselves while living up to their own highest standards. The cosmopolitanism I have in mind affirms both cultural distinctiveness and pan-cultural unity, which it can do because each is anchored in a similar moral and cultural striving. In order to assist peace, political, economic, scientific, and other efforts to reduce conflict must be informed by moral realism, most especially by a recognition of the need for leaders to have self-control and a corresponding cultural sensibility. I call this approach to peace “cosmopolitan humanism.”

I hasten to add what should be obvious, that sometimes cultural diversity expresses provincialism, intolerance, and brutality and is a major source of conflict. Diversity that is not humanized by moral and other universality but manifests self-absorbed eccentricity engenders friction and instability. Nationalistic arrogance and bullying caused terrible upheaval and suffering in the last two centuries. The great problem with what is ordinarily called multiculturalism is that it is quite unable to distinguish between diversity that enriches and diversity that degrades human life.

The history and culture of a people is the source of its social cohesion, outlook on life, and sense of direction and self-worth. Its past shapes it in countless ways, some of which are not even visible to the superficial eye. Every people has less than admirable traits of which it would do well to try to divest itself, but it also has admirable qualities and great achievements in which it can take pride. These must be absorbed and appreciated anew by each generation. Efforts in the present to improve society need to be adapted, through creativity, to the historically evolved cultural heritage. A people cannot give its best without being itself. To impose on a people a supposedly superior pattern of conduct that is wholly alien to its traditions produces disorientation and a split personality: the alien patterns can only produce mechanical and artificial imitation, while putting the people at odds with its deepest sources of self-respect and meaning.

When people in different societies develop what is most admirable in their culture, however, they may at one and the same time be cultivating their own heritage and a common human ground, to the extent that their work is inspired by the universal values of goodness, truth, and beauty. As they culturally enrich their own society, they strengthen their ties to other peoples. Though inevitably marked by the distinctive past and present of their particular society, their cultural efforts are in their expression of man’s higher humanity a bridge to equivalent attempts in other societies.

Genuine human universality has nothing to do with uniformity. It consists of universal qualities that are always adapted to the historical circumstance of time and place. This is done by means of human creativity that synthesizes the universal and the particular. Cosmopolitan humanism is based on the recognition that many different, historically formed cultural identities and individual creative acts can manifest one and the same higher quality of inspiration—though obviously more or less successfully in particular cases. Representatives of different cultures can come together as fellow human beings not despite but through their cultural individualities, the latter sharing not all particulars but the same quality.

Cosmopolitan humanism, then, simultaneously and indistinguishably cherishes the unity of purpose that is intrinsic to pursuing life’s higher values and the diversity that must characterize attempts to realize that potential. Moral and cultural activity at their best affirm the unity by harmonizing and dignifying the diversity and affirm the diversity by varying and enriching the unity. This humanizing discipline contrasts sharply with universality that is understood as distinct from and even opposed to particularity and as abstract rather than concrete and particular.

In the Western world especially, it is widely assumed that a culture of enlightenment, democracy, and equality is far along in supplanting the ancient moral and cultural traditions of the world. But supposed progressives seem not to realize the extent to which social and political arrangements that they deem desirable and even take for granted—including respect for individual rights, rule of law, freedoms of speech and association, and tolerance—actually evolved from the old moral and cultural traditions that progressives deem expendable or unacceptable. Many of their designs for society and the world are parasitic on old character traits that they have no plans for trying to preserve. They want behaviors of a certain kind but do not attend to their moral and cultural preconditions.

If there is any truth about human nature in the ancient moral and religious traditions, the progressive mind ignores or downplays the greatest threat to domestic and international peace: that man is his own worst enemy. This is the case not only, as enlightened intellectuals might concede, in that man is sometimes less than fully rational but also in that he is prone to letting egotistical passion and rashness run roughshod over conscience. Leaders and people who are able to show the appropriate self-restraint are such because they are in the habit of scrutinizing and purifying their own motives. Protracted moral and cultural efforts have shaped their character, limiting the self-indulgence that puts them in conflict with others.

Because historical circumstances vary so greatly, societies are bound to differ in how they approach and express respect for higher values. Yet there is among the ancient civilizations of the world a remarkable confluence of moral and cultural sensibility. It includes far-reaching agreement about what constitutes admirable human conduct and good leadership. From China to Europe and the United States there is a rough consensus on the attributes of a great man or gentleman. He is first of all a person of moral integrity. Of particular relevance in this discussion of prospects for cordial relations is the belief that the exemplary person exhibits self-restraint, humility, modesty, dignity, and good manners. The ancient Greeks warned against hubris, against the belief that you are one of the gods. For Christianity, the greatest sin is pride. Our primary moral obligation is not to condemn the weaknesses of others and demand that they improve but to attend to our own weaknesses. Christianity roundly condemns the conceit and moral evasiveness of always finding fault in others. In the words of Jesus of Nazareth, “Take the log out of your own eye first, and then you will be able to see and take the speck out of your brother’s eye.”

The notion of universality that I associate with cosmopolitan humanism contains no implication that persons, peoples, and civilizations should conform to a single model of life or that universality can be imposed by means of political engineering. It may be helpful to contrast genuine universality with a type of universalism that today is particularly common and influential in the United States. I am referring to an ideologically intense variant of the Enlightenment mindset that assumes a single political system is desirable and even mandatory for all societies and should be everywhere installed, through military means if necessary. I have called this ideology the new Jacobinism. The French Jacobins summarized their putatively universal principles in the slogan “freedom, equality, and brotherhood.” They saw France as the redeemer of nations. The new Jacobins speak of “freedom” and “democracy,” and they have anointed the United States.

It is important to understand how radically that form of universalism departs from the older Western tradition. Although proximate in time, the ideas behind the U.S. Constitution of 1789 and those behind the French Revolution of the same year are fundamentally different. The framers of the Constitution held a view of human nature and society that was essentially classical and Christian, whereas the French Jacobins were inspired by Rousseau.

According to the classical and Christian traditions, moral virtue is indistinguishable from personal character. It is first of all a form of self-rule. It means subduing and ordering the passions. Jacobin virtue, by contrast, is primarily and directly political. It is a sense of moral superiority, of being a benefactor of mankind. Because it thinks of itself as a desire to improve vastly the lives of others, this virtue feels itself entitled to the power needed to change the world. This virtue, then, is not a wish to control and improve self but a wish to control and improve others. Far from curbing the will to power, Jacobin universalism stimulates it.

The U.S. Constitution assumes a need for the opposite, to restrain power, that of the people as well as that of their representatives. America’s leaders were not interested in ideological crusading. They hoped to set a good example for others, not impose their will on them. But the new Jacobins radically re-interpret what they call America’s “Founding principles.” These principles belong to all mankind, they assert, and they justify armed American global hegemony.

The U.S. Constitution granted to the central government only limited and shared sovereignty. It left power for the most part in state and local institutions and, above all, with the people themselves in their private capacities. The purpose of the constitutional arrangement was unity in diversity. The union of states would help harmonize and draw strength from diversity, not abolish it.

Because neo-Jacobin universalism favors abstract, ideological homogeneity and disdains particularity, it runs counter to old American attitudes and Western traditions. In practice as well as theory, abstract universalism means a lack of respect for regional or local diversity and for the special needs and opportunities that they reflect.

It does not follow that the most common form of modern multiculturalism with its cult of diversity and its so-called “historicism” offers a humane alternative. By its frantic and therefore disingenuous denial of universality, postmodernism makes history chaotic. Without a unity or continuity of human experience, no consciousness could exist. There could be no history, only wholly disjointed and therefore meaningless experiential fragments. It is different with what I call cosmopolitan humanism. Though it recognizes and affirms the variety of human existence and its inevitably contextual, contingent, “historical” character, it sees particularity as potentially expressive of universality.

In political theory the school that most sharply attacks historicism is that of Leo Strauss. Interestingly, postmodernism shares with anti-historicist universalism, whether of the Straussian or neo-Jacobin variety, the assumption that universality and particularity are incompatible. The postmodernists attack universality in the name of radical historicity. The anti-historicists disparage historical particularity in the name of ideological universality. Neither side recognizes the possibility of synthesis of universality and particularity, a potential that is central to cosmopolitan humanism.

The dialectical and synthetical relationship of universality and particularity may be suggested in the most general terms. The good, the true, and the beautiful do in one special sense lack specific form: they are magnetic qualities that an infinite number of yet to be completed moral acts, philosophical thoughts, and works of art may have. But in a different sense the good, the true, and the beautiful exist for us only in historical particulars: they are embodied in countless acts, thoughts, and works of art—in loving, morally responsible behavior, wise books and lectures, outstanding poems and compositions—which come alive in the present as we relive and try to absorb them and let them inspire more of the same.

Far from being an ahistorical, abstract standard, genuine universality must be freshly discovered by individuals for themselves in their time and place. It must find expression in concrete particulars. The resulting variety enriches and deepens man’s historical existence. Because universality has no other opportunities for articulation than the historical circumstances of persons, it can have no single manifestation, only a single qualitative form. Although true universality creates qualitative affinities across borders, it is inimical to a global uniculture. Goodness, truth, and beauty reveal the common human ground as they show themselves in the uniqueness and distinctiveness of persons, peoples, and civilizations.

This kind of particularity harmonizes diversity. It makes for more than a flimsy and transitory unity. When peoples and civilizations cultivate their selfhood at the highest level, their efforts are not only compatible with unity. They are the unity. To the extent that unity is possible among human beings, it is achieved through diversity.

It should be possible to see, then, why cosmopolitan humanism is indistinguishable from patriotism, that is, from a proper love of one’s own society. The genuine patriot, as distinguished from the self-absorbed, arrogant nationalist, cherishes what is admirable about his own traditions, as judged by transnational, universal standards. Without the patriot’s deep rootedness in his own culture’s sense of goodness, truth, and beauty he would not have the preparation and sensitivity to appreciate comparable efforts in other societies. Moral, intellectual, and aesthetic phenomena from around the world that strike rootless, ill-informed, ill-prepared observers as having nothing in common are found by the patriotic cosmopolitan to be both qualitatively kindred and intriguingly, appealingly different.

Cosmopolitan humanism contrasts sharply with the prescriptions for regional or global unification that are advanced by people who have no deep cultural roots and who for that reason are at home in no particular place. For such pseudocosmopolitans no truly common human ground exists and no truly transcultural appreciation is possible. Peace has to them no special moral and cultural preconditions. The dominant breed of Eurocrat exemplifies the type. Just as this person has no strong attachment to any country, so does this person have scant interest in history and even less in the philosophically demanding issues of morality and culture. The typical Eurocrat makes do instead with a smattering of trendy ideas. It is anomalous and potentially dangerous that people with little familiarity with and even a strong prejudice against the moral and cultural traditions of mankind tend to set the tone in discussions of how to achieve better international relations.

A technocratic and presentist cosmopolitanism is not merely ill-conceived, it positively undermines prospects for lessening tensions by diverting attention from what peace and unity most require: that persons, peoples, and civilizations put a resilient check on self-absorption and arrogance and cultivate what is best in their traditions. To stress that need is to make a central philosophical point, but it is first and foremost an urgent call for greater realism in addressing the problem of peace. It is realism in keeping with the shared moral and cultural heritage of humanity.

Claes G. Ryn is professor of politics at Catholic University and chairman of the National Humanities Institute. He is the author of A Common Human Ground: Universality and Particularity in a Multicultural World and America the Virtuous: The Crisis of Democracy and the Quest for Empire.

Comments