The Trade War China Intends to Win

Donald Trump is defining his presidency—and his nation is defining its future—as he struggles to meet China’s all-out assault on the American economy.

Americans like to say that “no nation ever wins a trade war,” but that’s not what the Chinese think. There are winners in trade wars, which is why China has been waging one for two generations.

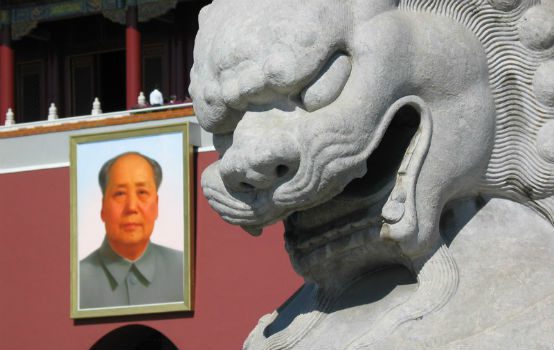

Beijing, in its quest to strengthen its state-led system, has engaged in predatory tactics for four decades, since the beginning of the “reform era” in December 1978. Beijing’s attack on the American economy over this period has been methodical and insidious, especially in recent years under rulers Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping.

Hu’s era, the decade-long period beginning in 2002, saw first a drift and then a pronounced trend towards more statist policies, especially his “indigenous innovation product accreditation” rules, part of a national strategy to force foreign companies to surrender technology.

Xi, during his first five-year term as Communist Party general secretary, continued the regressive moves, bolstering the state sector through various means, like creating monopolies through mergers, increasing state subsidies, and implementing industrial policies. As part of this effort, Beijing relentlessly attacked foreign competitors through, among other tactics, highly discriminatory law enforcement and malicious rule-making.

Of greatest concern is Beijing’s use of stratagems to take, by one means or another, intellectual property. The other concern is China’s development of its own technology by coercive tactics, like the enforcement of national policies that violate Beijing’s trade obligations. In this regard, Exhibit A is the now-infamous Made in China 2025 policy, an attempt to dominate 10—now effectively 11—tech sectors.

And there is outright theft. Today, as detailed in the 2017 update to the report of the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, America each year loses an amount in excess of $225 billion—and perhaps as much as $600 billion—“in counterfeit goods, pirated software, and theft of trade secrets.” This does not include all losses due to the infringement of patents.

Much, if not most, of the theft is thought to be perpetrated by Chinese parties or by others on Beijing’s behalf.

Apart from the small-scale steel and aluminum tariffs imposed under the authority of Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, Trump’s tariffs are intended to stop this theft. The tariffs under discussion today have been—or will be—imposed under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974.

Although the Section 301 tariffs have trade implications and are imposed under the authority of “trade” legislation, they are not, strictly speaking, trade remedies. They are remedies for criminal conduct.

That criminal conduct is an existential threat to the American economy, which is heavily innovation-based: if the United States cannot commercialize its innovation, it does not have much of a future.

To ensure that future, the Trump administration, to its credit, has begun to fight by levying 301 tariffs on $34 billion of Chinese goods. Trump has talked of tariffs on $500 billion of imports from China, but these measures, no matter how large, are “far from sufficient,” says Alan Tonelson, a Washington, D.C. trade analyst. “In the near term,” he told The American Conservative, “the U.S. also needs a ban on Chinese or China-related investment in U.S. companies possessing considerable intellectual property or other advanced knowhow.”

Trump late last month decided not to impose an across-the-board ban on Chinese investment, instead opting to endorse legislation, the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act. The bill, sponsored by Senator John Cornyn, the Texas Republican, would strengthen the powers of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, the Treasury-led interagency task force that reviews proposed foreign takeovers of U.S. assets.

The legislation is desperately needed. Beijing is acquiring U.S. tech quickly. One of its under-the-radar tactics is funding start-ups in Silicon Valley.

Today, China can buy tech that way. Tomorrow, maybe not. Washington will surely tighten the rules as relations with Beijing continue to erode.

And they should. For four decades, American policymakers have thought the way to obtain Chinese cooperation was to maintain generous, friendly, and open policies, hoping Beijing would reciprocate. A ruthlessly pragmatic Beijing, however, saw that there would be no penalty for bad conduct and so continued, among other things, undermining the American economy.

“The long-term goal is opening up the Chinese market and getting China to be a fair competitor,” Fraser Howie, the co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundation of China’s Extraordinary Rise, told TAC this month. “That looks unlikely. Under Xi Jinping, it is very much China First regardless of the nice global rhetoric.”

Because Howie’s skepticism is warranted, the clash between America and China looks like a decades-long struggle, “a new ‘Cold War’” as the official China Daily termed it early this month. Xinhua News Agency, Beijing’s mouthpiece, recently said the fight was a “battle for the nation’s fate.”

In that war or battle, Washington will undoubtedly adopt policy approaches once thought to be extreme, like Tonelson’s “disengagement.” “Longer term, the most effective way to fight Chinese IP theft is to minimize China’s access to any valuable intellectual property to begin with, through a policy of strategic disengagement with the Chinese economy that includes moving the relevant supply chain links out of the PRC,” he maintains.

One form of that disengagement involves stopping American companies from funding Chinese tech development. “Sweeping restrictions are needed on new American corporate investment in Chinese entities participating in the Made in China 2025 program,” says Tonelson.

Rules like that would stop, for instance, Tesla’s just-announced plan to not only build a plant, big enough to make 500,000 cars a year, in Shanghai, but also to locate R&D in China. One of the sectors targeted by Made in China 2025 is electric vehicles.

Elon Musk, Tesla’s chief executive, was lucky to make his announcement before harsher views become widely accepted in America’s capital. On Wednesday, a congressman asked me if the administration could stop Musk.

Musk as of today is free to go ahead with his China plans, but he still has to worry about what Trump will do in the not-too-distant future. “He has preached a confrontation with China for 30 years,” Steve Bannon told Politico. “The one thing he has been the most consistent on for his entire career is the economic threat posed by China.”

“Reagan had Russia,” Bannon said. “Trump has China.”

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China and Nuclear Showdown: North Korea Takes On the World. He has given numerous briefings in Washington and other capitals and has frequently appeared on cable and other media outlets.

Comments