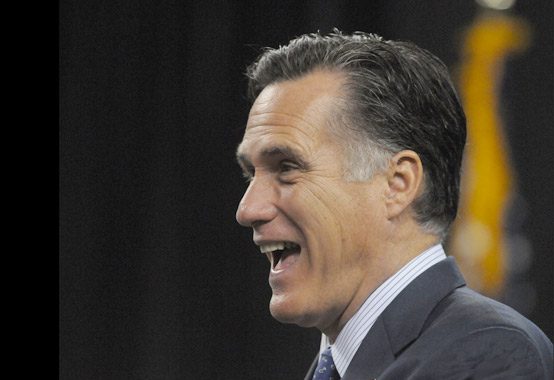

Romney Capitalism

Edward Lewis: “We don’t make anything, Phil.”

Phil Stuckey: “We make money, Edward.”

—“Pretty Woman” (1990)

There’s a subplot in the movie “Pretty Woman” that serves as an apt metaphor for the business careers of George Wilkin Romney and his son Willard Milton “Mitt” Romney. The Edward Lewis character, played by Richard Gere, is in the same line of work that was once Mitt’s. His business buys the stock of ailing companies up to a majority stake, using money from investors and banks. Once these companies are under his control, they are then broken up and sold off piece by piece for a profit.

Lewis’s firm is trying to do this to a Los Angeles shipbuilding company whose exec is played by the venerable actor Ralph Bellamy. At a dinner meeting—which includes the star of the film, Julia Roberts—Bellamy’s character mentions once encountering Lewis’s father, Carter, who turns out to have been estranged from his son before his death. The scene subtly suggests father disapproved of son for more than just being kicked out of college.

It’s pure speculation what the elder Romney thought of his son’s business in comparison with his own career as an auto executive. But their divergent paths illustrate how the once all-powerful manufacturing sector that produced men like George Romney for public office gave way to the all-powerful financial sector from which Mitt springs.

George Romney knew how to work with his hands, whether on his parents’ potato farm in Idaho or in his father’s construction business after his family sold the farm and moved to Salt Lake City. He also knew debt and deprivation in the Glasgow slums during his Mormon mission to Scotland in the late 1920s and in the hardships his family faced during the Great Depression.

He worked his way from the bottom to the top, starting as an apprentice with the Aluminum Corporation of America (Alcoa) in 1930 before rising to become a leader of the Automotive Committee for Air Defense and the Automotive Council for War Production during World War II. Thereafter he was a general manager of the Automobile Manufacturers Association in the late 1940s before finally becoming CEO of the American Motor Company (AMC) in 1954.

That’s where Romney built his reputation as an innovative businessman before launching his first campaign to become governor of Michigan in 1962. He streamlined management, cut executive salaries (including his own), fended off takeover attempts, produced cars like the Rambler, cultivated good relations with United Auto Workers, and established a profit-sharing program. When Romney took over at AMC it traded at $7 a share. When he resigned in 1962, it was trading at $90 a share.

By contrast, Mitt Romney always knew he was well ahead by virtue of being his father’s son. George Romney, like many of his generation, wanted to make sure his children didn’t have it as tough as he did. So Mitt grew up in the ritzy Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills and attended its exclusive prep school Cranbrook with the sons of other auto executives and Detroit businessmen, then went on to Stanford and Brigham Young universities, before law school and business school at Harvard in the mid-1970s.

Top companies wanted the cum laude graduate Romney working for them. But the young, would-be executives like Romney being churned out by the top business schools at the time were not always eager to jump into established industries, perhaps with good reason. The industrial old guard, especially in manufacturing, had to deal with strikes, oil embargoes, inflation, and cheap imports eating into their profit margins at a time when the country was struggling to shake off a decade-long malaise. Mitt didn’t use his Harvard MBA and law degree to follow his father into the auto industry. Instead, he went into management consulting, which led to his hiring by Bain and Company in the late 1970s. Following that, in 1984 he founded Bain Capital.

The elder Romney didn’t exactly earn an MBA. (He briefly attended a junior college in Idaho, as well as the University of Utah and a business college affiliated with the Latter-day Saints.) What he learned was taught to him by leaders in the cradle of American industry, the steel and automotive businesses. He no doubt learned a great deal helping to construct the “Arsenal of Democracy” in Detroit’s factories during World War II. An unavoidable lesson was that industry and manufacturing are what gave the nation its power and led it to victory. What was good for industry—if not for General Motors, which George Romney wanted to see broken up along with the other Big Three automakers—was good for the country. Preserving such industry and providing for its labor force while making a profit for shareholders underpinned his business decisions at AMC.

The younger Romney, by contrast, attended Harvard at a time when the Chicago school of economics was gaining influence in business schools across the country. The lessons being taught in that era said it didn’t matter who made what and where as long as labor costs were low. The world was becoming one big interconnected market, and what mattered was the free flow of goods, services, and labor. As far as the U.S. was concerned, if the nation maintained its technological and financial edge and was able to keep markets around the world open with its military might, all would be okay. Attempts to regulate this emerging global market were to be contested, and existing regulations (like Glass-Stegall) were to be repealed.

Mitt Romney backers can point to the fact that Bain Capital under his leadership helped to create companies such as Staples, the big-box office supply store (which put out of business local supply stores that used to be a prominent part of downtowns across the country). But soon Bain moved from start-ups to leveraged buyouts: purchasing the stock of existing businesses with money borrowed against their assets and then either fixing the companies or selling them off to make the 113 percent average rate of return Bain delivered to its investors.

That aspect of his business has made Romney an easy target for his political opponents because it involved layoffs and bankruptcies. What may have been taught as the genius of “creative destruction” in a Harvard classroom devastated long-established companies, along with the lives of their employees. Both George and Mitt may have created, but Mitt also destroyed.

If Romney the Elder didn’t have much influence on the business career of Romney the Younger, he did help bring him into the other family trade: politics. George Romney not only encouraged his formerly apolitical son to run for the U.S. Senate in 1994 but actually moved into his Boston home, went on the campaign trail for him, and served as an unofficial adviser to the campaign.

George Romney had helped to rewrite Michigan’s state constitution between 1959 and ’61, before running for governor in 1962 after he had made his fortune. He served two terms, the latter of which overlapped with his 1968 bid for the White House. His son has so far followed a parallel trajectory: he first made his millions, then became governor of Massachusetts (2003-07), and since then has been running for president.

There have been many comparisons made between the two Romneys’ presidential campaigns in the context of both being “moderate” candidates that had to court the party’s conservative base. But a man of George Romney’s background must have well understood the financial backers of the early conservative movement, the self-made industrialists who ran companies like Acme Steel of Chicago, Wood River Oil of Wichita, Rand-Ingersoll of Rockford, and the Cincinnati Milling Machine Company. His résumé would have passed muster with the movement’s California business wing—such figures as Henri Salvatori, Walter Knott, Holmes Tuttle, and Patrick Frawley.

In fact, George Romney and Barry Goldwater came from similar Western backgrounds: both were self-made businessmen (Goldwater as a department store owner), both wanted to see big labor unions broken up, and as presidential candidates both made sometimes awkward moral appeals to voters (One of Romney’s campaign slogans in 1968 was “The Way to Stop Crime is to Stop Moral Decay!”). They parted ways over civil rights, toward which Romney, as governor of an industrial state with a large black population, took a more activist view. (It was politically helpful as well: Romney carried 30 percent of the black vote in his 1966 re-election.) Conservatives may have felt real animosity towards a Nelson Rockefeller or a William Scranton, but one doubts they felt the same way about George Romney. His failures as a national campaigner, more than opposition within the party, doomed his presidential ambitions.

What makes Mitt Romney seem like a “moderate” today is not just his record as governor—his individual-mandate healthcare reform, his support for abortion rights before 2005, and other positions he struggles to explain away—but his managerial personality as compared to the crusading temperament of much of the Republican Party’s base. The profile of his donor base reinforces Romney’s image as something other than a right-wing man of the people: by the end of March, Romney’s campaign had raised about $87 million, most of it not from the small donors who support more ideological campaigns but from fellow businessmen like Lewis Eisenberg, a senior advisor to the famed Kohlberg, Kravitz, Roberts private equity fund; or Julian Roberts, the head of Tiger Management; or hedge fund founders Paul Singer and John Paulson and Romney’s buddy from Bain, Edward Conrad. Employees at Goldman Sachs have been very generous to Romney, giving him nearly a half-million dollars.

As AP writer Stephen Braun has noted, “New York’s financial institutions are the hub of Romney’s fundraising.” Birds of a feather. Compare this to his father’s main campaign bankrollers, Detroit businessman Max Fisher, who made his money in oil reclamation and gas stations, and Romney’s fellow Mormon and Marriott Corporation founder J. Willard Marriott (after whom George Romney named his son).

Perhaps Mitt is not so much his father’s son after all, when it comes to politics; a better father figure would be Nelson Rockefeller himself. “Rockefeller Republicans” were in reality political opportunists, as pointed out by author Geoffrey Kabaservice in his recent book Rule and Ruin. They were partisan Republicans but not ideological ones. As New York governor, Rockefeller supported some very strict drug laws and ordered the crackdown on the Attica State Prison riot—hardly liberal things to do. Republicans of his kind have drifted with the direction of the party, which in recent years has moved to the ideological right. To survive politically, politicians like Mitt Romney have had to go with the tide. George Romney didn’t do this, so his political career capsized.

Perhaps Mitt is not so much his father’s son after all, when it comes to politics; a better father figure would be Nelson Rockefeller himself. “Rockefeller Republicans” were in reality political opportunists, as pointed out by author Geoffrey Kabaservice in his recent book Rule and Ruin. They were partisan Republicans but not ideological ones. As New York governor, Rockefeller supported some very strict drug laws and ordered the crackdown on the Attica State Prison riot—hardly liberal things to do. Republicans of his kind have drifted with the direction of the party, which in recent years has moved to the ideological right. To survive politically, politicians like Mitt Romney have had to go with the tide. George Romney didn’t do this, so his political career capsized.

At the end of “Pretty Woman,” Richard Gere not only gets the girl but also saves the shipbuilding company. There is no girl for the happily married Romney to get—certainly no one speaking in his ear telling him there’s a better way to do business. The ghosts of his father’s past simply can’t show any other kind of success: the car company no longer exists; the presidential campaign has gone down in history as a monumental failure, a punch line remembered only for George Romney attributing his support for the Vietnam War to “brainwashing” by military propaganda.

Romney the Younger has made more money and gone farther in public life than Romney the Elder ever did. Whether it ultimately earns him more respect is another matter.

Sean Scallon is a freelance writer and journalist living in Arkansaw, Wisconsin.

Comments