Robert Nisbet’s Conservatism

What does “conservatism” mean today? Warring factions inside and outside the Republican Party, trading insults, claim the word exclusively as their own. Are these noisy claims valid?

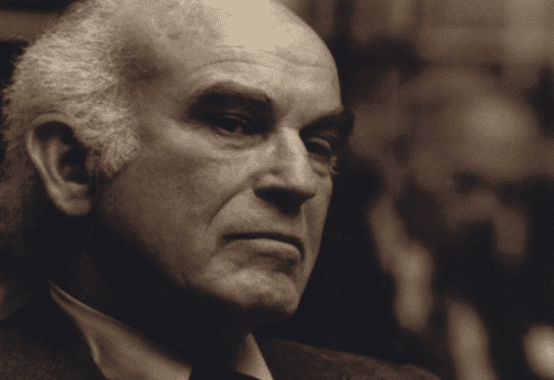

A major architect of postwar conservative thought, Robert Nisbet (1913–1996), might help retrieve a term thrown around recklessly and nearly drained of substance.

Nisbet was one of several outstanding 20th-century sociologists—Pitirim Sorokin and Edward Banfield are two others—almost buried by the progressive bias in the social sciences and political philosophy. Yet the New York Times columnist Ross Douthat writes that Nisbet’s 1953 book, The Quest for Community, is “arguably the 20th century’s most important work of conservative sociology.” Nisbet’s interest in ideal relations between the state and the individual places him in the school of Edmund Burke and Alexis de Tocqueville.

As a young professor in the 1950s, Nisbet worked amid fierce ideological disputes over communism and subversion on the Berkeley campus. During a long academic career Nisbet sought to contain rising statism and the “loose individual.”

Nisbet and my father had been classmates at San Luis Obispo High School in Depression-era California. In 1931, he and my father were the backfield for the school’s modestly composed football team. One grim Kodak black-and-white photograph shows the two of them, badly suited up, standing on a bleak playing field ringed with Tom Joad-like Model Ts. All but two games in their senior year were canceled for fear of polio.

In the class yearbook, called Tale of the Tiger, amid young men and women whose aspirations were to become insurance agents and stenographers, here’s a handsome Robert Nisbet and under his senior picture: “Likes: To discuss philosophy. Objective: To reform the world.”

Nisbet and my father went on to enroll in the state university at Berkeley, escaping California’s dead-end hinterlands. They remained lifelong friends.

When I started teaching, my father advised me to get to know his academic friend better, and I did. In 1972, Nisbet was at the University of Arizona, and at 58 he could not know that a glorious late-in-life career was shortly to appear before him. American universities were inflamed by the New Left and the counterculture. George McGovern had just set the Democrats in a new direction.

In one of our first “adult” conversations, when I asked earnestly about equality, Nisbet insisted on making a bright-line distinction between what was possible, equal opportunity and equality before the law, and what was not, a coercive dream of managed, equal outcomes.

During the McGovern years, contesting equality’s self-evident virtues was shocking coming from a senior professor and established social critic. But as I listened to Nisbet’s faultless reasoning, that was the moment, I realized a good while later, I became a “conservative” in mind.

The growth of national government during the 1960s through massive military and administrative expansion, Nisbet feared, prefigured “the centralized state of the masses,” empowered by the “crumbling of the pre-democratic strata of values and institutions” that “alone made political freedom possible.” Worse, he thought, a growing number of clients might welcome its power and largess at the expense of family and freedom.

Centralization, egalitarianism, and coercive multiculturalism were not the right answers, Nisbet would reiterate throughout his career. What induced social harmony and individual fulfillment, he observed—long before Robert Putnam wrote Bowling Alone (2000)—were communities of churches and schools, volunteer groups, families, and tribes. Localism, kinship, and liberty make a society secure. Leviathan smothers the human spirit through sheer size, regulation, bureaucracy, and fiat.

If unobtainable forms of equality become cornerstones of national policy, he argued, the onslaught on institutions to try to achieve the impossible would be unlimited. Intrusive state power promising to cure inequality would let government take on powers formerly reserved to other authorities. Stripped of religion, the public was imbibing liberal elixirs that rendered individuals blameless, turning them into victims of a society that “glistens with corruption,” he once said to me. Guilt and wishful thinking quickened the politics of equality.

Nisbet’s essays and reviews for Commentary and The Public Interest advanced his visibility as a social critic. He became a natural ally of neoconservatives floating new domestic-policy ideas in New York City and Washington, D.C., drawing the attention of Norman Podhoretz, Irving Kristol, and William F. Buckley Jr., and gaining access to their coteries in Manhattan. With the assistance of Robert K. Merton, he obtained an endowed professorship at Columbia University, rescuing him from relative obscurity at the University of Arizona.

Nisbet’s best line ever, and he meant it: “A square block in Manhattan has more community than the entire city of Tucson.”

The success of his 1975 book, Twilight of Authority, was rather a surprise. The writing, as with much of Nisbet, ranges from dense and stilted to lucid and aphoristic. It is not an easy book. But its discursive, prescient, panoramic indictment of shifting authorities found a distinguished audience, and it drew him further into debate over socio-cultural policies.

Leaving Columbia in 1978, Nisbet moved to Washington, DC, to join the American Enterprise Institute. It was the perfect moment, since the swing to conservative ideas had begun and the neoconservatives were hot. With great pride, Nisbet received the Jefferson Medal in 1988. From the award’s lecture came a book, The Present Age, in which Nisbet drew a full portrait of the runaway state and the counter-culture’s beau ideal, the “loose individual,” unmoored from conventions and free to pursue the “deviant, delinquent, alienated, anomic, bored, narcissistic.”

Nisbet had no patience for sloth. His youthful circumstances had been Depression rough, and he escaped a troubled household. With studied poise, he was unfailingly civil, with measured, formal manners, and considerable sangfroid.

He thought that boredom was civilization’s number-one self-poisoner. Wealth and leisure could undermine the collective good sense of the masses, he felt, stimulating euphoria at a cost. Efforts to offset boredom—through video games, television, sports, pornography, or drugs—could be fatal to community. Facebook’s artificial communities and the politics of Twitter, he might say, give the illusion of social cement while causing the real thing to crack.

He thought that boredom was civilization’s number-one self-poisoner. Wealth and leisure could undermine the collective good sense of the masses, he felt, stimulating euphoria at a cost. Efforts to offset boredom—through video games, television, sports, pornography, or drugs—could be fatal to community. Facebook’s artificial communities and the politics of Twitter, he might say, give the illusion of social cement while causing the real thing to crack.

Much of what Nisbet foresaw decades ago has come to be. Americans surf big-screen HDTV channels, seeking relief and distraction. Hoping politics will make things right, the nation follows the plot like a serial—some on Fox, others on CNN—accepting politics as a televised reality show. Donald Trump is only Exhibit A.

Nisbet, who died in 1996, might today observe that the crafty, nihilistic Clintons and mesmerizing Trump did not happen by accident. Politics as mass entertainment leads to demagogues, eager for the spotlight and ready with E-Z talking points.

There is nothing new under the sun, he might add. Messianic leaders willing to override political tradition vexed Plato, Plutarch, and the Founders. All warned how speedily demagogues can undo democracies. American citizens should worry about the same thing today.

Gilbert T. Sewall, director of the American Textbook Council, is co-author of The USA Since 1945: After Hiroshima and editor of The Eighties: A Reader.

Comments