Legal Pot Goes Local in Colorado

Possessing and smoking marijuana in Colorado is now as legal as buying a six-pack and drinking a beer, but with towns and cities as culturally far apart as Colorado Springs and Aspen, the new law is being handled in very different ways.

“Things are going exactly as planned, more or less,” assured Mason Tvert, a spokesman for the Marijuana Policy Project. “Some are embracing the change, they recognize the voters have done this and it’s not going anywhere. Others are trying to resist it.”

Tvert is based in Denver, which is both the capital and the largest Colorado city to move forward with plans to open marijuana shops, beginning on Jan. 1. On Oct. 1, the state began taking applications for licenses to sell marijuana commercially from existing medical marijuana dispensaries (all other prospective licensees can start applying in July 2014). According to Tvert, 15 different localities (towns, cities, or counties), including Denver, have given their dispensaries the green light to apply (a process requiring a wagon-full of paperwork and thousands of dollars in fees and bonds).

Meanwhile, a large number of localities are currently drafting regulations for marijuana businesses in their communities, he told TAC. “Localities get to decide where [shops] are located, the zoning, how many licenses may be given out in one area.” They also get to decide whether to impose an additional local tax on pot sales, and whether marijuana can be used in public places like coffee shops or parks (though don’t expect any Amsterdam-style cafes—smoking anything is banned in Colorado’s bars and restaurants).

Bringing new revenues into state coffers was one of the biggest selling points of Amendment 64—especially among fiscal and libertarian conservatives (who also see prohibition as fueling the violent black market and failed Drug War)—when it was passed by Colorado voters by a nearly 54 percent majority last November. They will vote in another referendum this Election Day on whether to impose state taxes on marijuana, including a 15 percent excise tax (on top of the current 2.9 percent sales tax) and a 10 percent “special tax” that could be raised to as high as 15 percent. Some estimates have marijuana sales generating upwards of $130 million in additional yearly tax revenue.

But while all those new potential tax dollars may be alluring for cash strapped municipalities, over 100 counties and towns throughout Colorado have either already banned the commercial sale of marijuana or have set moratoriums on the process.

“Marijuana sales are banned in far more places than they’re allowed,” blared an online headline the day after the application process for licenses opened Oct. 1. “Dry Towns Dampen Pot’s Spread,” exclaimed another in Time magazine.

These proclamations may be unduly dire, say pro-pot supporters, who note that while many localities are still undecided about how to move forward, or whether to even “opt in,” that doesn’t necessarily make them ambivalent toward the new law—at least not yet.

As of this week, according those compiling the yeas, nays, and delays, there were indeed 66 outright prohibitions, effectively making those towns and counties “smokeless”—an option written into the new law. Observers say there are at least 46 localities on track for opening stores on Jan. 1 or later in the year. Some of those have placed moratoriums on new businesses, but will allow existing medical marijuana dispensaries to apply for commercial licenses. Others are still drafting regulations but plan to “opt in.”

That leaves the rest either undecided or leaning toward a ban. A lot depends on whether a healthy majority of their residents were behind Amendment 64, and whether they have supported the state’s medical marijuana law, which has been in effect since voters approved it by 54 percent in 2000.

Most of the 66 localities that have already banned the commercial sale of marijuana had already outlawed medical marijuana dispensaries. Under the new law, though, they cannot stop adults from possessing, growing, or using marijuana behind closed doors. They can only refuse to allow so-called “pot shops” or the public imbibing of marijuana products within their jurisdictions.

According to Coloradans who spoke with TAC, these reluctant localities just don’t believe that legalizing marijuana is the answer. They fret about undesirable elements coming out of the woodwork, scaring away families and tourists, and worry about the new law’s effect on children.

“My first and foremost concern is public safety,” Don Knight, a member of the Colorado Springs City Council, tells TAC, “especially keeping recreational marijuana out of the hands of minors.” The city council passed a ban, by a contentious vote of 5 to 4, in July.

While fiscal conservatives have rallied for medical marijuana and decriminalization laws across the country, social conservatives have generally held firm against them, for the reasons Knight outlines. Colorado Springs, Colorado’s second largest city after Denver and nicknamed America’s (evangelical) Christian Mecca, is the perfect example. While it does allow medical marijuana dispensaries within city limits, and it passed Amendment 64 by about 5,000 votes, vocal conservative opposition to the new law had a major impact on the council’s decision to ban it, according to reports.

That opposition featured in large part, the military, which has a significant presence in Colorado Springs, including the Fort Carson Army installation, Peterson Air Force base, Schriever Air Force base, and the United States Air Force Academy.

“Two pillars of our community are tourism and the military,” Knight says. “Families won’t bring people to Colorado Springs if they’re scared of marijuana. The military won’t move their bases here if they’re scared of marijuana.” His assessment wasn’t all hyperbole—active duty officers were among those lobbying against marijuana stores in the city. According to one report from The Gazette back in June, Fort Carson’s Maj. Gen. Paul LaCamera was heard frequently telling audiences that legalized pot is “against good order and discipline.”

Others suggested the bases might lose money if the city were marijuana friendly. “Marijuana use is incompatible with military service,” retired Air Force Gen. Stephen Lorenz, told the paper.

But while many places—including other major Colorado cities, like Thorton, Westminster, and Centennial—have revolted against so-called “cannabisiness,” plenty of towns and counties are not just resigned to the new reality, but are actually embracing the “weed friendly” label.

In fact, officials like Sal Pace, commissioner of Pueblo County, which plans to move forward with commercial sales, say they are happy to get the spillover business from smokeless neighbors like Colorado Springs. “Every time one of our neighbors bans it, we cheer,” Pace told the Denver Post. His people tell TAC that Pueblo is courting marijuana testing facilities and other marijuana-related commerce, and is serious about pot serving as a long-term economic driver.

“Pueblo has some of the most industry-friendly laws in the state,” noted Shawn Hauser, an attorney for Sensible Colorado, which is working with Pace on these issues.

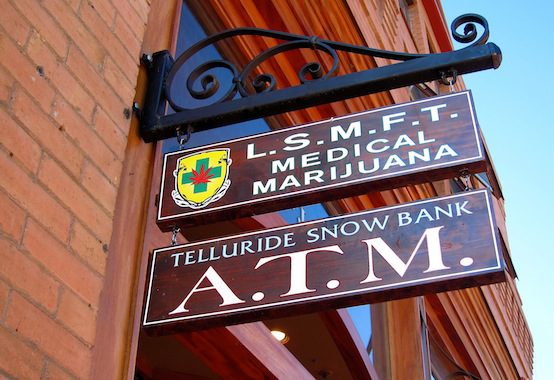

Colorado’s famed tourism centers remain divided, so far, on commercial sales. Tourists, particularly to the state’s famed ski resorts, brought in $17 billion last year. Places like Telluride are moving forward full speed with legalization, planning for at least three new retail stores in the main business district. Aspen is allowing for new shops but capping the number at eight. Breckenridge, known as a “the Amsterdam of the Rockies,” has banned retail stores from the downtown but not elsewhere.

Vail, which has a ban on medical marijuana dispensaries, has placed a moratorium, which expires in December, on drafting regulations for commercial pot.

Some have groused that the “patchwork” of smoke and smokeless localities might lead to a de facto black market despite state legalization, especially if the closest retail opportunity is hundreds of miles away from a smokeless municipality. Tvert, though, doesn’t anticipate that happening.

“The underground market will be largely eliminated relatively quickly, and I expect a number of localities that are not currently poised to allow retail stores will come around,” he said, noting that folks can always grow their own while the laws evolve.

[Localities with bans] will recognize that adults in their communities are using marijuana, which will still be allowed, and they will want to start reaping the economic benefits from sales, as opposed to those people all purchasing marijuana and paying sales taxes in other localities.

That may the case, but officials who are vehemently opposed on moral or public safety grounds might just work harder to place as many restrictions on use as possible and market that as a selling point for their towns, said Colorado Springs Councilor Knight.

Cities that have very active city councils, and city leadership that are trying to bring tourism dollars to their cities and tourism districts, they will walk the halls of Congress and walk the halls of the Pentagon and they will put on family ads that say, ‘come to our town, we don’t allow marijuana!’

It all depends on what kind of tourist you are.

Kelley Beaucar Vlahos is a Washington, D.C.-based freelance reporter and TAC contributing editor. Follow her on Twitter.

Comments