Voters in Europe Just Smashed the Mainstream Establishment

Last week, the elections took place for the European Parliament, and one thing was clear: the European Union is driving voters to the edges of the political spectrum.

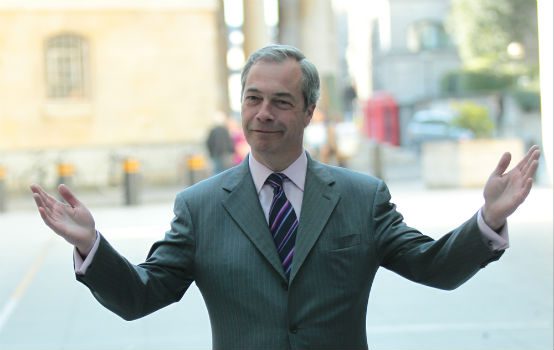

Elections should always make writers reflect on whether the pieces they’ve written in advance of the voting turn out to be correct. Here at TAC, I’ve said that Marine Le Pen can win in France by doing nothing (she did and she won), that nationalists could get together and represent a strong political force in the European Parliament (they are strong, though they now seem unlikely to get along), that Nigel Farage will upset British politics if it remains in a stalemate (the Brexit Party won by a large margin and Farage is more popular than ever), and that Emmanuel Macron will ally with anyone to get his political reforms pushed through (the jury is still out on that one).

The center-right and center-left have lost support, leading the two major groups in the European Parliament, the European People’s Party and the Socialist Alliance, to lose their majority. They can now only confirm the European Commission, the executive in Brussels, if they find a third partner. This role will be filled by Emmanuel Macron’s movement: a staunchly pro-EU group of liberal democrats, environmentalists, and progressives. At a press conference the night of the election, center-right lead candidate and possible next Commission president Manfred Weber said that he could also envision the Greens as a part of this grand coalition. This would rally the entire European left (with the exception of hardline Marxists and communists) behind a new executive.

Why the Greens? Because fear.

Weber has watched a green wave crash on Western Europe. In Germany, the Greens made massive gains, as they surfed the trendy wave of climate marches in Europe. The center-right is trying to make sure that voters see no difference between the traditional parties and the environmentalists by, first, taking up part of their platform, and, second, making them part of their coalitions. However, these same Greens made demands to Weber prior to the election, and striking a deal could prove difficult.

Overall, pro-EU parties and environmentalist parties did well in the elections. In the United Kingdom, the second biggest winners turned out to be the Liberal Democrats, who ran on simply canceling Brexit.

On the other side of the spectrum, reformists, euroskeptics, and nationalists have also made gains. Marine Le Pen beat Macron in France, Matteo Salvini is up 28 percent in Italy, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán added more seats for his party in the European Parliament, Poland’s nationalists confirmed their popularity with voters, the German populist Alternative für Deutschland is up by 4 percent, and Nigel Farage eviscerated the Conservative and Labour parties. European voters have seemingly made up their minds as to whether they support or don’t support EU policies.

The efforts by the European Union to keep this from happening hasn’t worked. “Fake news” legislation, restrictions on political advertising, and EU-funded campaigns telling euroskeptics not to vote failed to prevent a revolt against the mainstream. The political fringes in the European Parliament are now stronger than ever, to the point that they may not be fringes anymore. Whoever thought that parliament sessions in Brussels were not sufficiently exciting will now get their money’s worth.

However, that same political establishment seems unimpressed by the upset they’ve just seen. There’s been no reflection and no reconsideration. It’s as if it did not happen.

While the European Commission has been attempting to sanction governments in Poland and Hungary, explaining that they do not act in their own citizens’ interest, those same citizens have now confirmed the parties in charge of those governments at the ballot box. Whether or not Hungarian and Polish policies are a problem is a discussion for another time, but it seems certain that sneering from unelected bureaucrats does not sway voters into backing a pre-written narrative. Who could have predicted that?

Here’s what happens next: the European Parliament will constitute itself and the political parties will attempt to establish groups through which they will speak and work in Brussels. While Macron tries to win over new members for his pro-EU alliance, the nationalist and euroskeptic forces will struggle to find common ground. Farage has reportedly walked away from talks with Marine Le Pen and Matteo Salvini. Fights over positions and salaries are apparently preventing the rebels from joining forces.

The European elections have thus laid the ground for a new polarization of EU politics. As parliament commences, we will see whether that translates into a battle of political blocs unlike any we’ve seen before.

Bill Wirtz comments on European politics and policy in English, French, and German. His work has appeared in Newsweek, the Washington Examiner, CityAM, Le Monde, Le Figaro, and Die Welt.

Comments