Why Architectural Elites Love Ugly Buildings

A libido for the ugly…something that the psychologists have so far neglected: the love of ugliness for its own sake. —H.L. Mencken

When the British government recently set up a Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, the appointment of philosopher Roger Scruton to chair it brought a frisson of excitement among conservative-minded architects and commentators. It seemed to signal that the anti-Modernist counter-revolution that has recently been gathering momentum in architectural circles, particularly in the U.S. and UK, was moving beyond journalism and into the realm of public policy. The optimism was short-lived as Scruton was abruptly sacked (and then reinstated) in a panicky reaction (by the Minister for Housing) to a storm of character assassination coming from Britain’s all-powerful media commentariat. This story is now old news, but the question remains as to what, if anything, a “building beautiful” initiative might actually achieve in the face of an architectural culture that seems to prize novelty above all else.

All Western publics still treasure their nation’s classical and gothic architectural marvels and flock to them as “tourist attractions,” but among the architectural cognoscenti, a conceptual line-in-the-sand must be drawn—somewhere in the early 20th century—marking the end stage of this kind of beauty. Architectural beauty, as commonly understood for most of Western civilization’s history, must from then on and for evermore be continuously and radically reinvented.

A widespread public bewilderment at the “Deconstructivist” showcase buildings that they are told is great modern architecture is well known. But less well understood is that most of the Western world’s architectural academy are militantly disdainful of most popular conceptions of architectural comeliness. And this disdain extends not only to the “classical” in public and commercial buildings but equally to the average person’s ideal of a home and neighborhood (the focus of the Building Better; Building Beautiful Commission’s brief). This disconnection between popular and highbrow conceptions of beauty and ugliness now has quite a long history, going back to at least the 1950s.

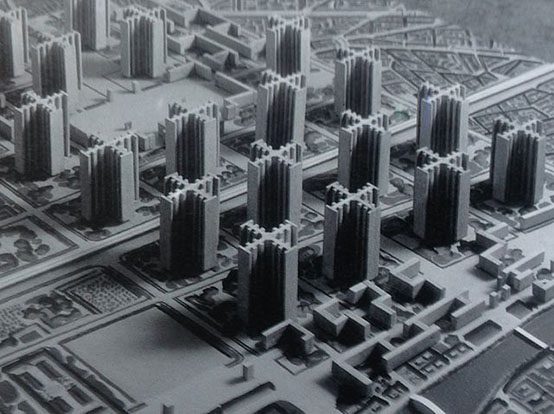

In large parts of post-World War II Europe, the bombs of war were followed by a three-decade-long blitz of dogmatic Modernist social engineering and megalomaniac town planning, most of it taking inspiration from the then hugely fashionable theories of the Swiss architect who called himself Le Corbusier. The most forgiving thing one can say of it all was that the trauma of the war had given rise to a widespread mood of alienation from all things past. But the consequences of this alienation from the past and an intelligentsia intoxicated with utopian dogma were a tragedy, and one that unfolded on a vast scale.

Great swathes of eminently salvageable traditional urban fabric fell victim to so-called “slum clearance,” to be replaced by a utopian landscape of impersonal and often windswept “public” open space that quickly became a joy only to the thug and criminal. These barren landscapes were dotted with high-rise blocks, concrete beehives that could fulfill the utopian fantasies of their creators if their mainly working-class residents had somehow been mentally reprogrammed. Meanwhile, mature town centers, with their urban fabric comprising a complex tapestry of building types, were casually violated and desiccated, their history now counting for nothing. A “libido for the ugly” was in full flux.

At least it’s over now? Well, yes and no. Certainly the arrogant certainties of utopian collectivism mercifully crumbled in the 1970s. Almost everyone now understands that to let architects and town planners decide what society’s “needs” are—and then dream up megalomaniac schemes for the wholesale satisfaction of these needs—is akin to kitting your small child out with power tools and a bag of cement, and setting him loose to decide what your home needs. Everyone, that is, except in the ivory towers of architectural academe; its luminary authors of revered set texts and in the more high brow professional journals.

Almost everyone now understands that the Corbusian legacy was entirely malign, even if they have never heard of the man himself. And the question is often asked how his grim concrete megalomania ever came to hold such sway in the first place. Step inside a Western school of architecture to pose this question, and you might get a shock. You are likely to find that the so-called “fathers” of the International Style in general, and Le Corbusier in particular (he of the tabula rasa concept of urban renewal in which everywhere “must” be “totally rebuilt” using only concrete), are still revered as the philosopher kings of architecture.

***

I had first-hand experience of this dynamic in architectural education in the 1980s. In my school, the status of “Corb” (as we were encouraged to affectionately call him) as a hero was a given, and dissenting from this position was risky. Such is the power of group-think which universities are, sadly, no less prone to than anywhere else. To be fair, nobody was still plugging the megalomaniac aspect of their hero; his knock-down-the-center-of-Paris side. All those undeniably God-awful tower blocks for “rationally” housing “the people” that sprang up all over Europe in his name? Well, we were assured, they could not be blamed on Corb; it was just that his more pedestrian architectural acolytes hadn’t properly understood what he had meant. In addition to the persistence of Corb-hero worship itself, two cancerous aspects of its radical mindset have survived intact in our schools of architecture.

One is the idea that an architect aspiring to greatness must also aspire to novelty. It is this imperative to “innovate” that underpins the diagrammatic design concepts of the Deconstuctivists. There is of course nothing wrong with innovation per se; it is the knee-jerk compulsion to innovate, or “reinterpret”—as a kind of moral imperative—that is the mid-20th-century aesthetic legacy. To be fair to the profession, I would come to the defense of much innovative public and commercial architecture, most of it by architects that the public has never heard of. Tragically though, these unpretentious and unsung essays in steel, glass, and masonry have been eclipsed in the public imagination by the “starchitect” bling that is currently turning the centers of our great cities into a collection of (in James Stevens Curl’s memorable phrase) “California-style roadside attractions”.

The other cancer is the idea that building design has sociological, psychological, and macro-economic dimensions that the architect—simply by virtue of being an architect—is competent to judge. What really matters to your average architecture student is drawing—which is fine, and just as it should be, until the vain idea emerges that their drawings represent some kind of implicit vision for mankind. At my school, any student’s design presentation had to include a verbal rationale—often post hoc and invariably half-baked—of how the form, massing, and materials of the design are expressive of such imponderables as the supposed psychological “needs” and “aspirations” of the users and the wider “community” that the building is to serve. The students were simply reciting the bogus language of their tutors—in which buildings might be said to be “fun,” “thought provoking,” “democratic,” “inclusive” and other such nonsense.

By the late 1980’s, “tradition” was once again recognized as an important aspect of an architect’s education—at least in theory. Of course, by then had come a visceral reaction in society against tower-block utopia, and “conservation” and “preservation” was fast becoming the new vogue. In architecture-school-speak, however, respect for tradition does not mean quite what you might imagine; it might mean, for example, that you still propose to insert some manifestly alien infill development into a gap in a row of period terraced houses—perhaps even the proverbial upended shark, at least metaphorically if not literally. But crucially now, instead of bragging of your iconoclasm, you would go to equally verbose lengths to demonstrate that you were merely respectfully “reinterpreting” the traditional forms. Architects now “must” reinterpret tradition, so one must beware of architectural academics espousing “tradition.”

To again be fair to the contemporary profession, the recent past has not been all negative. The aesthetic and build-quality of mass speculative housing—typically “traditional” brick-clad boxes with pitched roofs laid out along residential roads and cul de sacs—may fall short of one’s ideal but it is probably as good now as in the 1930s, and certainly infinitely better than the ‘50s to ‘80s. It is important to remember that building, like art and music, has never been of a uniformly high standard and the search for some aesthetic final solution leads inexorably to something out of the set of a sci-fi B movie.

***

Is there a way forward from all of this for architectural education? Many believe there is and certainly some, both in the academy and in the profession, are working very hard to find a way. It is easy to be pessimistic. But things do change and some very talented young architects won’t all be groupthink types. Despite the great drag weight of the current architectural establishment, a renaissance of a kind has, in recent years, begun to stir, as manifested in the growth of an anti-modernist counter-revolutionary journalism (particularly in America). Thus now, a student who resists being dragooned into the Corb/Decon groupthink of his/her tutors need not feel as isolated as they would have been in my day.

The quality of architectural education has a societal importance that is hard to overstate. Goethe famously wrote that architecture is frozen music. It is a compelling metaphor, but if architecture really was music then we would all be able to choose an urban environment composed entirely of beautiful buildings. With all other art forms, you can seek out what is good and shun the rest, but escaping bad architecture is much more difficult. So a renaissance in architectural education is long overdue and there are alternative possible paths that it might travel.

One would be for the dominance in architectural theory of grand societal “visions” (Modernism together with its various this-and-that-ism progeny) to wither away, leaving only purely aesthetic judgements; albeit ones informed by spatial, contextual, constructional, and technological understanding. This view is perhaps best expressed in Sir Reginald Blomfield’s 1934 observation that “…literature and the written word established a disastrous domination in arts not their own and all sorts of strange ideals were introduced and pursued with an enthusiasm which constantly missed the mark, because most of its aims were irrelevant to the art of architecture.” On this view, architectural theory can be encompassed in Vitruvius’s ancient and eloquent aphorism—firmness, commodity, and delight.

Another approach would improve the depth and quality of architectural education for its students. A vital part of this would be the development of an understanding that the psychology of a person’s relationship to their private dwelling differs radically from their relationship to other building types. Of all the Modernist fallacies, perhaps the greatest was lumping together all building types into a single mold. Many people, including myself, are quite happy to be dazzled by steel and glass in their airport or corporate headquarters, but not in their residential neighborhood.

I am fond of the print on my wall of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water and can imagine it being someone’s dream home. For the great majority, however, their dream of domestic bliss is located in some-or-other variant of an archetypal pitched roofed dwelling house—and it is this that deserves to be “respected.” To insist that the aesthetics of dwelling must be “modernized” to suit some perceived advancing zeitgeist is almost as absurd as proposing that any of life’s simple pleasures must be modernized; that maybe even sexuality be modernized? Come to think of it though, there are some today who may indeed be advocating something along those lines too.

Graham Cunningham has contributed to The New Criterion, Quadrant, Spectator.au, and various other publications.

Comments