Who Are the Most Influential Urbanists?

Words on the Street highlights the best writing on the built environment we’ve encountered recently at New Urbs. Post tips at @NewUrbs.

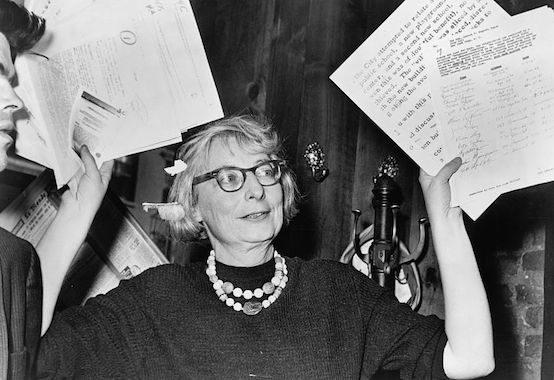

The 100 Most Influential Urbanists

The results are in, and Planetizen readers have chosen the “Most Influential Urbanists” of all time. And, yes, we mean all time. Names on the list date back as far as 498 BCE, but there’s also no shortage of contemporary thinkers, activists, planners, and designers in the final list of 100. It probably won’t surprise anyone that Jane Jacobs won this vote by a long shot, basically lapping the competition. [Read more…]

—Planetizen

The Thirty Years’ War: New Urbanism and the Academy

The (so far) the unbreachable chasm between New Urbanism and what now passes for architectural culture consists of opposite conceptions of the relationships of place, time and objects–not small matters. For architects, the culture of objects, their history and the discipline of making them are infinitely rich subjects. For urbanists, objects, especially buildings, have meaning only as the constituent elements of places. This is not just a matter of I’m more interested in this and you’re more interested in that—like say botany and astronomy. Botanists and astronomers have nothing against one another—unless they happen to be competing for faculty resources or parking. By contrast, there is real animus between the object people and the place people. Each subject has its own historiography, one focused on canonical buildings, the other on the history of the city. They not only see each other as a threat to what they hold most dear, they regard each other as uncouth, uncultured philistines. [Read more…]

—Daniel Solomon, CNU Public Square

‘Instant Neighborhoods’ Don’t Make Great Cities, But DC Insists on Them

From an urban design standpoint, “instant neighborhoods” rarely have the visual or social diversity that many people enjoy about urban places. Great neighborhoods evolve as a mixed collage of uses, buildings, activities, and people over time – resulting not just in a more interesting place, but also a more enduring one…. A diverse building stock also accommodates a fuller diversity of human activities, which ultimately turns out to be a significant economic strength, according to research from the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In its “Older Smaller Better” report, since expanded into an “Atlas of Reurbanism,” the Trust found that older neighborhoods had better economic performance across a range of factors: “The higher performance of areas containing small-scale buildings of mixed vintage suggests that successful districts evolve over time, adding and subtracting buildings incrementally, rather than comprehensively and all at once.” [Read more…]

—Payton Chung, Greater Greater Washington

Christ in the Garden of Endless Breadsticks

It’s not a coincidence that Olive Gardens tend to spring up near highways and shopping malls, within the orbit of mid-range hotels. Chain begets chain, or maybe chains are more comfortable among other chains — and in sufficient concentration they cause a little hiccup in the psychospace of reality, erasing any locality or sense of place, replacing it with a sanitized, brand-driven commercial hospitality. In downtown Salt Lake City or western Massachusetts or on the southern edge of the Chicago suburbs, wherever you see an Olive Garden, you’ll find something like a Quality Inn & Suites nearby. These accretions of commercial activity, stripped from geographic or historical identity, are what the French anthropologist Marc Augé talks about as “non-places.” … What it means to be a non-place is the same thing it means to be a chain: A plural nothingness, a physical space without an anchor to any actual location on Earth, or in time, or in any kind of spiritual arc. In its void, it simply is. [Read more…]

—Helen Rosner, Eater

How I-95 Broke Philly’s Waterfront (and What the City Is Doing to Fix It)

To walk to the river from any number of urban neighborhoods today is to encounter an elevated highway structure that is completely out of scale with the surrounding environment. In some places it feels dangerous to walk through the dark underpasses. And even in places where I-95 is already buried, it feels dangerous to cross over Christopher Columbus Boulevard, the at-grade arterial thoroughfare that runs parallel to the interstate along the Central Delaware. These things aren’t natural. “The highways are only roughly fifty years old,” says Harris Steinberg, executive director of the Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation at Drexel University. “In the scheme of things, that’s pretty new. We don’t know what new technologies are coming down the road, no pun intended. So we should seriously question whether we should rebuild these interstates in kind, as we are doing, for an outdated technology that is essentially anti-urban.” [Read more…]

—Jared Brey, Curbed

Comments