The Case for Minority Obstructionism

“Minority rule” is the latest buzzword emanating out of the Democratic party. Concerned about the likelihood of a 6-3 Republican-appointed majority on the Supreme Court and the possibility of Donald Trump once again winning the presidency sans the popular vote, progressives are indicting America’s republican system of government for impeding their numerical might.

The number-crunchers at FiveThirtyEight concluded that rural areas have two to three times as much representation in the U.S. Senate as do large urban cities, despite the two areas containing about an equal number of voters. “And of course, this has all sorts of other downstream consequences. Since rural areas tend to be whiter, it means the Senate represents a whiter population, too,” writes Nate Silver. It’s as if the upper chamber dials back the demographic clock twenty years.

“Republicans essentially get bonus points: They can be the less popular party and still get to govern,” complains Seth Masket in The Washington Post. “This is how a government loses its legitimacy…And it’s not a counterargument to say that the advantages the Republicans have today are ‘constitutional.’ In fact, that’s the heart of the problem.”

In The New Yorker, John Cassidy accuses the Republican Party of intensifying “a years-long effort to consolidate minority rule.” He calls it “egregious” that “when you consider the combined influence of the Electoral College and the Senate, both of which amplify the power of Republican voters living in less densely populated parts of the country, the empowerment of the minority—an overwhelmingly white and conservative minority” exercises “a baleful influence” on American society.

CNN anchor Don Lemon has the solution. “We’re going to have to blow up the entire system,” he told colleague Chris Cuomo. “You’re going to have to get rid of the Electoral College, because the people, the minority in this country decides who the judges are, and they decide who the president is. Is that fair?”

The amendment process makes these constitutional alterations problematic in the short term, but the ultimate goal is clear: the dismantling of institutional barriers to raw, uninhibited majority-rule. The result will be nothing short of the dictation of national policy from New York and California, while the voices and interests of smaller states and communities are smothered.

Republicans ought to straighten their backs against this fetishization of democracy. And they’ll find guidance in one of the first-rate minds of the nineteenth century.

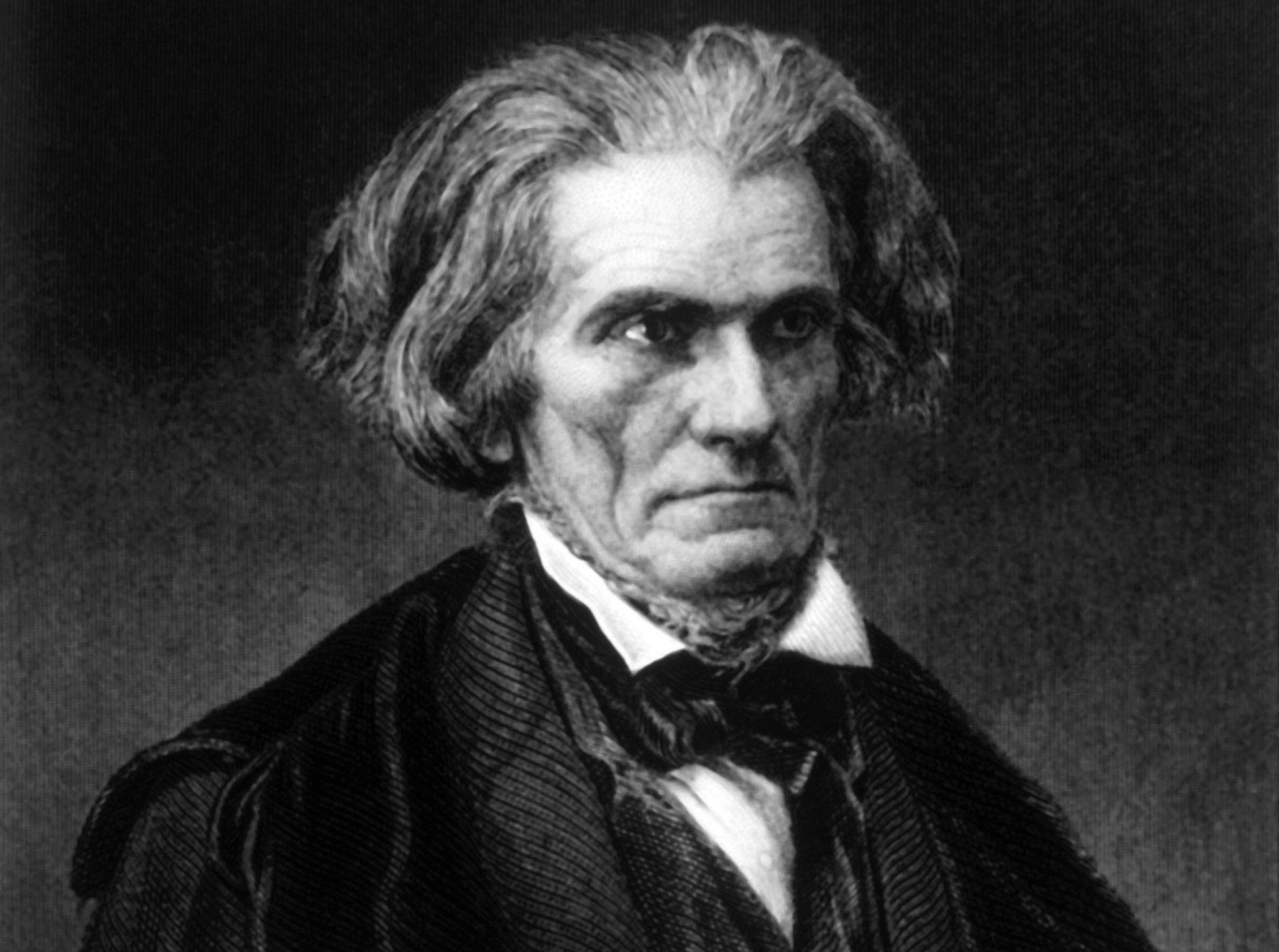

John C. Calhoun, in a forty-year political career, served as South Carolina’s congressman and senator, as both Secretary of War and Secretary of State, and as Vice President under two administrations. He began his journey as a fervent nationalist (for whom was coined the term “war hawk”) and ended it a dyed-in-the-cotton sectionalist. One of the “Great Triumvirate”—along with Henry Clay and Daniel Webster—Calhoun’s intellect burned like a furnace behind his piercingly blue eyes in an otherwise cast-iron expression.

“Calhoun’s political thought is more original and more closely reasoned than that of any other American statesman,” wrote Russell Kirk, the dean of modern conservative thought. Even John F. Kennedy praised Calhoun’s “profoundly penetrating and original understanding of the social bases of government [which] has significantly influenced American political theory and practice.”

The most consequential of Calhoun’s works, A Disquisition on Government, was written in the final months of his life as he coughed to death of tuberculosis. Published posthumously in 1851, it describes Calhoun’s vision of a constitutional republic governed by a concurrent majority.

Far removed from the starting point of John Locke and Thomas Jefferson, Calhoun rejected the natural rights tradition, and believed it was a foolish to subscribe to any theoretical “state of nature.” Instead Calhoun posited that government as an institution was divinely ordained, and that the human race always and forever existed under some form of authority.

But while God might demand governance, it is the responsibility of man to contrive its form. For Calhoun, that meant a constitutional republic able to balance the spheres of security (a necessity) and liberty (a privilege).

To achieve this harmony, participation from the voting public is essential but not sufficient. “I call the right of suffrage the indispensable and primary principle; for it would be a great and dangerous mistake to suppose, as many do, that it is, of itself, sufficient to form constitutional governments,” wrote Calhoun.

In an effective popular democracy, a voting majority turns “into an agency, and the rulers into agents, to divest government of all claims to sovereignty and to retain it unimpaired to the community.” But transferring the seat of authority to the masses does nothing to counteract “the tendency of the government to oppression and abuse of its powers.”

Calhoun recognized that every community—especially one as large as a nation—would have a diverse array of interests, pursuits, and situations. When the authority of the state is placed on the mass of people, it will “lead to conflict among its different interests—each striving to obtain possession of its powers, as the means of protecting itself against the others—or of advancing its respective interests, regardless of the interests of others.”

He accurately describes how political coalitions of expediency are formed, such as our Republican and Democratic parties, as vehicles for power:

For this purpose, a struggle will take place between the various interests to obtain a majority, in order to control the government. If no one interest be strong enough, of itself, to obtain it, a combination will be formed between those whose interests are most alike—each conceding something to the others, until a sufficient number is obtained to make a majority…When once formed, the community will be divided into two great parties—a major and minor—between which there will be incessant struggles on the one side to retain, and on the other to obtain the majority—and, thereby, the control of the government and the advantages it confers.

The purpose of a written constitution, then, is “to prevent any one interest, or combination of interests, from using the powers of government to aggrandize itself at the expense of the others…that is, by the adoption of some restriction or limitation, which shall so effectively prevent any one interest, or combination of interests, from obtaining the exclusive control of the government, as to render hopeless all attempts directed to that end,” wrote Calhoun.

We now arrive at the crux of Calhoun’s essay: forming a concurrent majority whose decisions regard not only a mathematical headcount but competing interests as well. Too often a numerical majority is wrongly identified with representing “the people” as a whole. A majority, even for example 60%, still only represents a portion of the total. A concurrent majority, on the other hand, uses preventative action to achieve compromises that respect all interests. If not, and a majority is able to dictate policy to a minority, you have an absolute government—whether superficially “democratic” or not.

That is why a political minority must possess “a concurrent voice in making and executing the laws, or a veto on their execution,” wrote Calhoun. “It is this negative power—the power of preventing or arresting the action of the government—be it called by what term it may—veto, interposition, nullification, check, or balance of power—which, in fact, forms the constitution.”

When Calhoun conceived of the concurrent majority in the 1830s and 1840s, he had in mind regional interests, whose “negative power” had to rely on nullification, and eventually, secession. Today, Republicans don’t require anything so exceptional; only a defense of the U.S. Senate, electoral college, and other centuries-old institutions that will ensure conservatives continue to have a seat at the governing table.

Calhoun hoped that a concurrent majority, “by giving to each interest, or portion, the power of self-protection, all strife and struggle between them for ascendency” would be prevented, and social feelings could “unite in one common devotion to country.” Judging from the above statements by the corporate press, who act as a vanguard for the burgeoning majority, Calhoun’s prayer for brighter days seems as fanciful as it once did in 1850.

Understanding the relevance of Calhoun’s political theory does not require adopting his worldview wholesale; conservatives should not reject natural rights theory or begin treating liberty as “a reward to be earned.” But Republican leadership must ascertain that the voice of their voters matters, and even if demographic trends condemn them to a permanent minority status, that doesn’t require sacrificing their core interests at the altar of majoritarian democracy.

Hunter DeRensis is Assistant Editor at the Libertarian Institute and a regular contributor to The American Conservative. You can follow him on Twitter @HunterDeRensis.

Comments