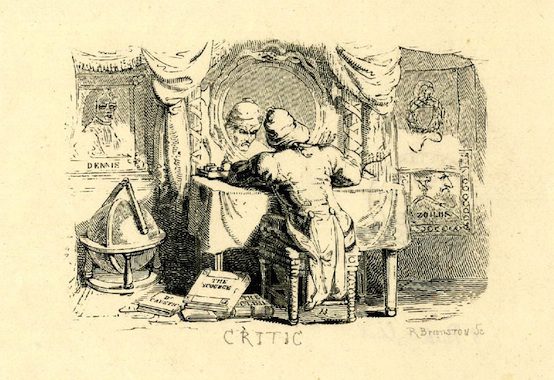

“Whitman is as unacquainted with art as a hog is with mathematics;” Or, Why Critics Should Write Negative Reviews

That, friends, is from an 1855 review of Leaves of Grass in the London Critic. You can find it and other such zingers in Rotten Reviews Redux.

Negative reviews have long been a staple of book criticism, but a number of editors seem increasingly uneasy with them. Isaac Fitzgerald, who has just been named Buzzfeed’s new books editor, suggests they are worthless in an interview with Andrew Beaujon at Poynter, and he says he won’t run them:

“Why waste breath talking smack about something?” he said. “You see it in so many old media-type places, the scathing takedown rip.” Fitzgerald said people in the online books community “understand that about books, that it is something that people have worked incredibly hard on, and they respect that. The overwhelming online books community is a positive place.”

He will follow what he calls the “Bambi Rule” (though he acknowledges the quote in fact comes from Thumper): “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say nothing at all.”

This summer, Evan Kindley, an editor at The Los Angeles Review of Books said that the publication has a policy of not running negative reviews of first books: “That most authors’ careers fade away on their own, and that it’s easy and not that interesting to eviscerate first-timers,” he tweeted. D.G. Myers responded: “As career counseling, or advice for the lovelorn, this is good stuff. As a literary ethic, it might be called the law of youth soccer—there are no losers, only winners. Trophies for everyone! I was surprised, though, at how much support Kindley received for his position on Twitter—and at how many misconceptions about reviewing abound.”

Indeed—misconceptions about reviewing and misunderstandings about the value of negative reviews despite negative reviews’ numerous values:

First, it’s called criticism for a reason because you’re, like, supposed to think and, like, evaluate the quality of something?

I write book reviews regularly for a number of places. Here’s how it works. Either you are assigned a book to review or you pitch one to the editor because the book looks interesting or noteworthy based on the blurbs or the pre-publication reviews or because the author is famous and everyone is going to cover it. You read it. You write a review. If it turns out to be a bad book, you critique it. If it is a good book, you praise it. Most often it’s a bit of both—praising here, quibbling there. This is the point of criticism—offering the reader an informed, considered evaluation of the quality and value of a particular work—after you have read it.

I have written a couple of negative reviews in my time. The most recent was of Marilynne Robinson’s When I Was a Child I Read Books. I like Robinson’s fiction and have mostly enjoyed her essays in the past, so I was looking forward to this volume. But it was a disappointment for various reasons, which I hope I stated and supported in the review. I used sharp language because clarity is important, whether you are praising or criticizing. I’ve read negative reviews that are so hedged they are almost useless—you know, the she-has-a-nice-smile type. This is cowardice not kindness—at least when it comes to reviewing. If a book is ugly, a critic needs to explain clearly why and support his or her judgment with proof, not hide behind veiled criticisms.

Second, and related to the above, writing or publishing only positive reviews is impractical and encourages an unhelpful kind prejudice (pre-judging) because it would seem to require either the suppression of negative reviews or a misguided attempt to determine whether a book is good or bad before reading it.

Sometimes page proofs are available three months in advance of publication, but usually it is closer to one or two. In either case, editors do little more than read the jacket, the first couple of pages or flip through it before making a decision about whether to review it.

In my experience, editors and critics are looking for books that would, again, be of interest to their readership, and, of course, good books are generally more interesting than bad ones, which is why few editors or critics rarely actively look for bad books to pan. The key term here is interesting. Hopefully, the book will be good, but it is impossible to know for sure until it has been read and evaluated by someone who has some expertise in the particular genre or topic.

If a book pegged as worthy of interest turns out to be bad, what would Fitzgerald or Kindley suggest editors do? Cancel the review and pay the critic a kill fee? Ask the critic to cut or hedge the criticism? Be so paranoid about picking a bad book that your book section reads like advertising copy? (The latter is what Tom Scocca suggests will happen in his funny and sharp response to Fitzgerald at Gawker.) In any case, I am not sure how a policy of no negative reviews would work.

Third, bad books are harmful. There seems to be the attitude amongst the only-positive-review crowd that bad books are really not that harmful to culture, and that, therefore, they should simply be ignored.

But mockery dissuades poor behavior and bad books, and bad books hurt literature. I have not looked at this systematically but the comparatively sparse number of negative poetry reviews over the years, particularly when compared to previous periods, has been very bad for contemporary poetry. There are so many bad books of poetry published today that they bury the good ones and readers are left with the erroneous impression that all contemporary poetry is terrible. The response to this is often to publish even fewer negative reviews because poetry is supposedly in such bad shape, which simply compounds the problem.

D.G. Myers put it this way in his response to Kindley this summer:

If I am to be an assistant, however, I will be an assistant not to book-buyers, but to literature. I have always admired philosophers—have always preferred their passion for their subject to that of writers and critics, whose lukewarmness is legion—because philosophers are the sworn enemies of vagueness and confusion. Error is never afforded a grace period. It is corrected without regard to personal circumstances, which are too many in any case (marital status, health, age, psychological condition) to factor in with any degree of certainty. Philosophy is what philosophers protect, not the tender green shoots of younger philosophers’ careers.

The LARB’s very sensitivity to first-time writers’ careers gives weight to what I have been saying for some time—namely, literature (or, rather, creative writing) has become a bureaucracy, which shields its employees from markets and thus tends over time to put its own interests above the public’s. Why should I care whether a young writer settles comfortably into a literary career?—especially a writer whose mediocrity eats at the public reputation of literature. (Just look what the bureaucratic careerists have done to what is now called literary fiction so that readers know to avoid it.)

Agreed.

Fourth, only publishing good reviews is harmful to the critic and to criticism. The value of criticism is in large part related to trust. If readers don’t trust a critic to provide them with honest and reliable criticism, why would they read his or her reviews? And if a critic or a book section never publishes a negative review, how can readers determine if either the critic or the book section is honest and reliable?

I find that there is a certain “clubiness” to a critic who only praises, and I often wonder if regular, fawning praise by a critic is not a result of a love of literature but rather a selfish attempt to put novelists or poets in one’s debt, which might be “traded” on later in one’s career. I can’t judge motives, of course, and there are lots of critics who love literature and who write almost exclusively positive reviews, but I can’t help but think there are wolves, too.

On this score, I find Fitzgerald’s remark that someone who writes online reviews somehow “understands” authors better rather silly. Sure it takes a lot of hard work to write a novel, and as a person, I respect other people who work hard, but as a critic, it is not the “hard work” I respect. It’s the novel or the poem itself.

Last, negative reviews are fun to read. And I thought Buzzfeed was all about fun? So I’m confused.

Fitzgerald is absolutely right that “The best moments in reading are when you come across something – a thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things – which you had thought special and particular to you. And now, here it is, set down by someone else, a person you have never met, someone even who is long dead. And it is as if a hand has come out, and taken yours.” But those are not the only enjoyable moments in reading either a book or a review of it.

Comments