The Wellness Scam, the Beginning of Modern Manners, and Hell

Remember, wellness is always a scam: “Sam Lipsyte’s novel Hark is a righteous send-up of self-help gobbledegook and the mindfulness industry.”

The beginning of modern manners: “In his new book, In Pursuit of Civility, Oxford historian Keith Thomas traces how the idea of conduct befitting a civilized people developed, especially in Stuart and Georgian England. During the Middle Ages, Europeans of every social class were more prone to unrestrained impulses. It was not uncommon to eat with one’s hands, belch at the dinner table, or relieve oneself in public. Renewed interest in ancient Greece and Rome during the Renaissance led to a new concern for how “civilized” people ought to act, according to Thomas. The use of the fork, which became common among the Italian upper classes in the 14th century and eventually reached England by the 18th, exemplifies this transition.”

“Artists collect differently from other people,” Frank Stella says in an interview at The New York Times. He explains how differently and why he displays fakes of his own work in his house.

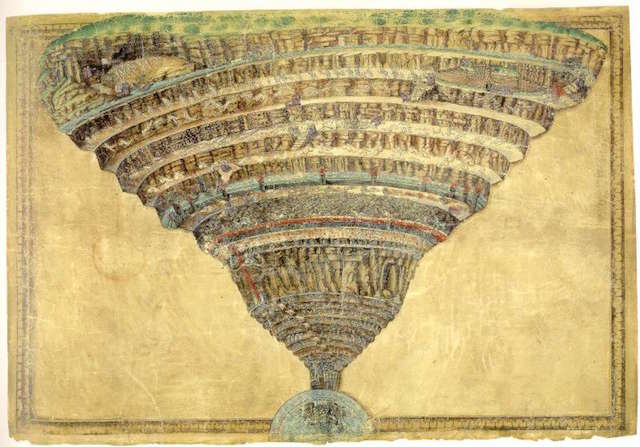

Nick Ripatrazone reviews The Penguin Book of Hell: “A visceral, meandering journey through hell written by a 12th-century Irish monk living in Regensburg, the Vision of Tundale does not have the focus of Dante’s later work—yet its confusing nature makes the narrative feel eerily authentic.”

The rhetoric of menus: “In May We Suggest, Pearlman sets out to determine how menus ‘steer consumer satisfaction and choice,’ if indeed they do so at all. After visiting over 60 restaurants in the Greater Los Angeles area—‘single- and multi-unit; chains regional, national, and international, eateries of varying ethnicities and cultural fusions […] vanguard and traditional; historic and new; full service, half-service, and self-service’—Pearlman challenges the rigid, programmatic directives provided by the consultants and the industry trade rags and the hospitality marketing journals. Menus certainly influence us, she claims. But not in the ways that they say we do.”

Google Books is broken: “I periodically write about Google Books here, so I thought I’d point out something that I’ve noticed recently that should be concerning to anyone accustomed to treating it as the largest collection of books: it appears that when you use a year constraint on book search, the search index has dramatically constricted to the point of being, essentially, broken.”

Essay of the Day:

In Spectator, Douglas Murray remembers the 30th anniversary of Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie for The Satanic Verses:

“In the bloody Iran/Iraq war Khomeini famously sent legions of his country’s young to die as suicide bombers. In the novel the exiled Imam (after a rant against the ‘apostate’ Aga Khan for drinking alcohol) extols a future when ‘Water will have its day and blood will flow like wine’ . . . For those few Muslims who did read the book and felt grievously offended, such contemporary politics were incidental. Of far greater significance, and grievance, was Rushdie’s re-imagining of the origins of Islam. Muslims who had never had the foundations of their religion questioned robustly found such passages so shocking as to be almost uncommunicable.

“Ziauddin Sardar was one such. In his 2004 memoir Desperately Seeking Paradise he described the sensation of reading The Satanic Verses when it came out. Years later he wrote, ‘It felt as though Rushdie had plundered everything I hold dear and despoiled the inner sanctum of my identity. Every word was directed at me and I took everything personally. This is how, I remember thinking, it must feel to be raped.’

“The section that would likely have caused most offense to even such a relatively progressive Muslim as Sardar would have been a passage which is among the novel’s most brilliant: a superlative dream sequence in which the dictation of the Koran is re-narrated into a tale of ‘Mahound’, the Messenger and his scribe ‘Salman the Persian’. ‘Mahound’ was a generally derogatory variant of ‘Mohammed’ used in the Middle Ages.

“In Rushdie’s novel the section satirizing the origins of the Koran is a searingly sad and humorous tale. Gibreel (Gabriel) appears to the Prophet who, ‘Salman the Persian’ finds ‘spouting rules, rules, rules . . . rules about every damn thing, if a man farts let him turn his face to the wind, a rule about which hand to use for the purpose of cleaning one’s behind. It was as if no aspect of human existence was to be left unregulated, free.’ The rules that flow include dietary laws, the way in which to kill an animal by bleeding and the positions in which sexual intercourse is and is not allowed. But it is when Gibreel gets into the business technicalities of how a man’s property should be divided that Salman wonders ‘what manner of God this was that sounded so much like a businessman.’ The result of this thought is the first crack in Salman’s faith. He begins to suspect that Mahound is not really taking dictation from an archangel but just making it up as he goes along.”

Poem: Salvatore Quasimodo, “Your Quiet Outpost” (translated by Julia Older)

Photo: Train in the Harz

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments