Social Justice Indoctrination, Van Gogh in London, and Defining the Soul

Good morning, friends. Life—well, politics—in America is crazy these days. Who would have imagined ten years ago that a gay man saying “all lives matter” would be denounced as racist? But there is a kind of comfort in remembering that people have always been crazy. Take the example of the daughter of Henry I, Matilda, empress of Germany and nearly queen of England. Her life, Peter Marshall writes in a review of her biography, “contains more dramatic plot twists than a season or three of Game of Thrones. In 1110, her father, King Henry I, last of the sons of William the Conqueror, dispatched her to Liège to become the bride (on reaching twelve) of Emperor Henry V. The marriage ended childlessly with Henry’s death in 1125, but not before Matilda had been politically tutored to serve as her husband’s regent in Italy. Meanwhile, Henry I suffered personal and political catastrophe in 1120 when the White Ship, a state-of-the-art vessel carrying his son and heir William across the Channel, went down after striking hidden rocks. There had never been a queen regnant as opposed to a queen consort in England – and, as Catherine Hanley points out in this lively and illuminating biography, in English, ‘queen’, unlike ‘king’, usually requires a qualifier to make its meaning plain. But Henry was determined that Matilda, rather than any of his illegitimate sons, would succeed him. He required his barons to swear fealty to her and sought to provide her with political ballast by arranging her marriage to Geoffrey of Anjou. He was twelve years Matilda’s junior and the couple seemingly detested each other, but the marriage served its dynastic purpose in producing a trio of sons. When Henry himself died in December 1135, Matilda should have ascended to the throne, but the news was slow to reach her, and the old king’s nephew Stephen of Blois raced across the Channel to have himself crowned in Westminster Abbey, to the acclaim of supporters who, in the words of a later chronicler, thought it ‘a shame for so many nobles to submit themselves to a woman’. The barons of England and Normandy divided, and for the best part of twenty years the realm was plunged into civil war. Ordinary people suffered predictably and horribly; it was a time when, according to another chronicler, ‘Christ and His saints slept’.”

What do future teachers learn at the University of Washington’s Secondary Teacher Education Program? A whole lot about “social justice activism” and not very much about teaching.

Algis Valiunas reviews the new Diderot biography: “One hates to restate the obvious, but some matters require to be repeated until their dire significance really sinks in. Intellectual freedom and diversity are in danger of being expunged. Formerly respectable universities have become the province of a mentally barren professoriate indoctrinating new generations of virtuecrats, who have no room in their minds for any thoughts that might defy the latest orthodoxy. The outlook is grim, rich possibilities are being foreclosed, and the past masters who formed our civilization have become objects of loathing, not to be spoken of without scorn. So one is grateful for small mercies, and this praiseful new intellectual biography of the French philosophe Denis Diderot (1713–1784) offers hope that serious engagement with the past is still possible in the academy.”

What can Aristotle teach us about the soul? “The soul is the most difficult and paradoxical thing in the world. In classical thought the soul is our form, which activates and animates the matter of our bodies and makes us rational and free beings. It thus provides our access to metaphysical being itself—the understanding of everything that is. The soul is the space where the light of philosophy shines. In Christianity the soul came to be understood as the spark of the divine or the image of God, and also immortal. (This latter view is ascribed to Aristotle by the disciples of Saint Thomas Aquinas.) A bit later, with the birth of modern science, the soul vanishes altogether. We speak today of the soul largely metaphorically and call the hard sciences “soulless”—by which we mean that chemistry, physics, and information technology are cold, deterministic, and heartless…David Bolotin, retired after a distinguished career at St. John’s College in Santa Fe, believes Aristotle can provide useful instruction here.”

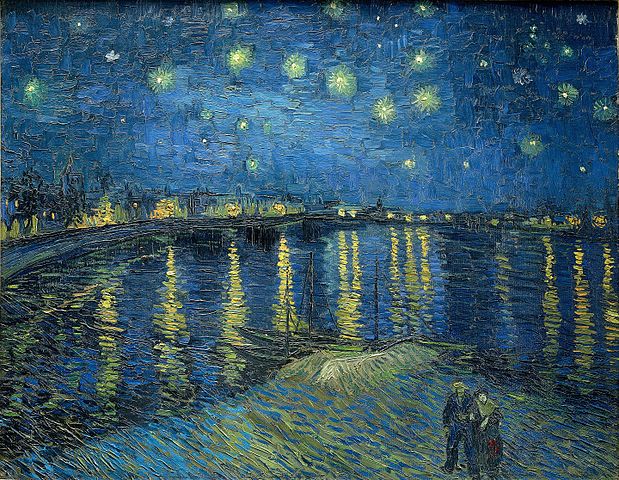

Van Gogh in London: “As Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône goes on show at Tate Britain, it is, in one sense, coming home. This might sound like wishful thinking. For the past half century the painting has hung in Paris, and its singing Mediterranean colours, which the artist himself described as ‘aquamarine’, ‘royal blue’ and ‘russet gold’, bear little resemblance to the murky half-tints of the Thames, which runs past Tate Britain’s Millbank site. Yet its spring exhibition, Van Gogh and Britain, is organised on the principle that the foundations of the Dutchman’s art, both his eye and his intellect, were laid not in the south of France, nor in the misty light of the Low Countries, but in London, where he spent three life-defining years (1873-76) as a young man.”

Why were Victorians obsessed with the moon?

Essay of the Day:

David Brown visits the island where George Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four:

“It’s hard to know what would be a good place from which to imagine a future of bad smells and no privacy, deceit and propaganda, poverty and torture. Does a writer need to live in misery and ugliness to conjure up a dystopia?

“Apparently not.

“We’d been walking more than an hour. The road was two tracks of pebbled dirt separated by a strip of grass. The land was treeless as prairie, with wildflowers and the seedless tops of last year’s grass smudging the new growth.

“We rounded a curve and looked down a hillside to the sea. A half mile in the distance, far back from the water, was a white house with three dormer windows. Behind it, a stone wall cut a diagonal to the water like a seam stitching mismatched pieces of green velvet. Far to the right, a boat moved along the shore, its sail as bright as the house.

“This was where George Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. The house, called Barnhill, sits near the northern end of Jura, an island off Scotland’s west coast in the Inner Hebrides. It was June 2, sunny, short-sleeve warm, with the midges barely out, and couldn’t have been more beautiful.”

Photo: Sagrada Familia from above

Poem: George Franklin, “Barcelona”

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments