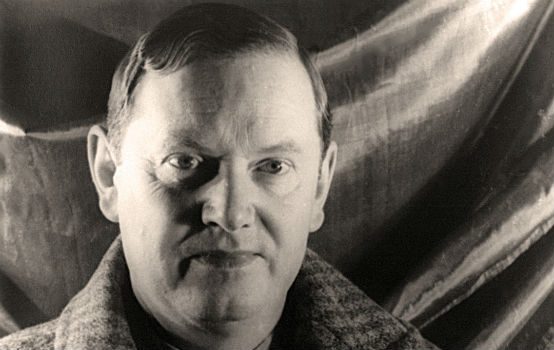

Revisiting Brideshead Revisited

Good morning. In The Critic, Alexander Larman revisits Brideshead Revisited at 75:

Seventy-five years after its publication, Brideshead Revisited remains Waugh’s most famous book, as well as his bestselling. Thanks in large part to its 1981 television adaptation with Jeremy Irons and Anthony Andrews, it has become iconic, even to those who have never read any of his other works or who have never heard of Waugh. It has ensured a steady flow of tourists to Christ Church in Oxford and Castle Howard in Yorkshire for decades – neither of which is shy about playing up the association – and a cursory search for the word ‘Brideshead’ on Instagram will immediately bring forward thousands, even tens of thousands, of pictures. Just like Nabokov’s Lolita, although less problematically, its name alone has become a brand. Is this why, then, it has become Waugh’s most misunderstood, even disliked, book?

Before it was published, Waugh was best known as a light comic novelist, something that he resented, both because it pigeonholed him and because he correctly believed that his semi-autobiographical masterpiece A Handful of Dust was considerably more accomplished than that implied. (He especially resented its commercial failure in America, later writing to Nancy Mitford that ‘they just printed a few copies, sent none out for review and let it flop.) He had converted to Roman Catholicism in 1930, and had written a biography of the Jesuit martyr Edmund Campion in 1935, but could not achieve the standing that he longed for. Therefore, he decided to do two out-of-character things. The first would be to join the army and attempt to see active service, and the second was to write a novel that would deal explicitly with Catholicism and sin.

The first was disastrous. Waugh was nearly 40 by the time that he was promoted to captain, and hugely unpopular with his men, being perceived as arrogant and rude. He was also involved in one of the great military debacles of the war, the 1941 evacuation of Crete, which he later wrote about in his trilogy of books about his experiences, Sword of Honour. His earlier novel, however, was a happier experience. He wrote it quickly, doing thousands of words a day, and had a high belief of its quality. He referred to it only partially in jest as ‘my magnum opus’ and described it to his friend Lady Dorothy Lygon, the inspiration for the book’s Cordelia Flyte, as ‘a very beautiful book, to bring tears, about very rich, beautiful, high-born people who live in palaces and have no troubles except what they make themselves and those are mainly the demons sex and drink.’

In other news: Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility is a terrible book. Matt Taibbi explains why, and Thomas Chatterton recommends what you should read instead.

Driverless cars, Bryan Appleyard writes in a review of Matthew Crawford’s Why We Drive, “are not primarily a caring, humane project to save lives, rather they are a scam designed to make our lives less interesting, less surprising and more profitable to the Silicon Valley monopolists. ‘The most authoritative voices in commerce and technology,’ he writes, ‘express a determination to eliminate contingency from life as much as possible, and replace it with machine-generated certainty.’”

Princeton renames school: “After years of activist demands and administrative resistance, Princeton University announced on Saturday that its governing board had voted to strip Woodrow Wilson’s name from its public-policy school, now to be known as the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs.”

A history of cheap food: “If you want to make a roomful of people argue with each other, one of the fastest ways is to express any kind of opinion about ‘cheap food’. To some, it is perfectly obvious that cheap food is an evil that results in underpaid farmers, degraded land and tortured animals. To others, it is equally obvious that cheap food is the great safeguard that stands between poor people and hunger.”

Gerald J. Russello reviews a new anthology of the best of the Free America magazine: “Despite policy and practical disagreements, the editors ‘would test every existing or proposed economic, political and social matter by a common measure: how the things at issue would affect the small and the human.’ In the inaugural issue, Agar makes the point that the contributors were united in their opposition to collectivism and plutocracy, and the journal would serve as ‘the meeting ground for those who are equally opposed to finance-capitalism, communism, and fascism,’ which were incompatible with democracy, since democracy could only survive when anchored by the widespread possession of property. The journal gathered contributors across from what we now would consider the ideological spectrum. Belloc contributed an essay, on ‘The Enemy,’ as did the editor of Commonweal, Michael Williams, on ‘The Great Tradition.’”

Charles Webb has died. He was 81: “Charles Webb, who wrote the 1963 novel The Graduate, the basis for the hit 1967 film, and then spent decades running from its success, died on June 16 in East Sussex, England. He was 81. A spokesman for his son John confirmed the death, in a hospital, but did not specify the cause. Mr. Webb’s novel, written shortly after college and based largely on his relationship with his wife, Eve Rudd, was made into an era-defining film, directed by Mike Nichols and starring Dustin Hoffman and Anne Bancroft, that gave voice to a generation’s youthful rejection of materialism. Mr. Webb and his wife, both born into privilege, carried that rejection well beyond youth, choosing to live in poverty and giving away whatever money came their way, even as the movie’s acclaim continued to follow them.”

The many names of the hare: “A book on folklore from 1875 told that the hare moved in close association with calamity – it was recommended that, passing a hare, you should recite: ‘Hare before, Trouble behind: Change ye, Cross, and free me.’ A Middle English poem gives the hare’s 77 names, which you should list if you pass one to ward off ill luck (few are complimentary). Seamus Heaney’s translation has, among others: ‘The creep-along, the sitter-still, / the pintail, the ring-the-hill, / the sudden start, the shake-the-heart, / the belly-white, the lambs-in-flight. / The gobshite, the gum-sucker, / the scare-the-man, the faith-breaker, / the snuff-the-ground, the baldy skull, / (his chief name is scoundrel).’ The hare’s actual name, lepus, came, the ancient Roman scholars said, from Latin levipes, ‘light foot’, and my God they deserve it. Brown hares can run at fifty miles an hour and jump ten feet: five times their own length in a single bound. To see a hare outrun a fox, zig-zagging to disrupt its momentum, is to know you are in the presence of the marvellous. Leverets are born with eyes open and fur on, ready to sprint: they live largely alone, do not make burrows, but rest in shallow indentations in the ground, never halting, always moving. ‘To kiss the hare’s foot’ is to be too late for dinner, according to Brewer’s Dictionary: ‘The hare has run away, and you are only in time to “kiss” the print of his foot.’ But they are not fast enough, of course, to outrun us.”

Photos: Maine

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments