Rebuilding Notre Dame, the Making of ‘Salvator Mundi’, and the Pulitzer Winners

Rebuilding Notre Dame: Nearly $1 billion has been raised so far to restore Notre Dame, and scans an architectural historian made of the cathedral before he died may help in that restoration: “Over five days,” Andrew Tallon and Paul Blaer “positioned the scanner again and again—50 times in all—to create an unmatched record of the reality of one of the world’s most awe-inspiring buildings, represented as a series of points in space. Tallon also took high-resolution panoramic photos to map onto the three-dimensional forms that the laser scanner could create.”

Emmanuel Macron has said France will rebuild the cathedral in five years. Most experts believe it will take much longer. “The roof and spire of Notre Dame, which was completely incinerated in Monday’s fire, were made of ancient oak. There were 13,000 beams in the church’s ceiling, and Guerry said about 3,000 trees would be needed to replace them.” Just finding those could take time.

There are (of course!) those who think the cathedral is just a symbol of white power and colonialism and so, really, not that important. Yes, really. Others argue that the cathedral should be rebuilt to reflect a secular, multiethnic utopianism: “‘The question becomes, which Notre Dame are you actually rebuilding?,’ he says. Harwood, too, believes that it would be a mistake to try to recreate the edifice as it once stood, as LeDuc did more than 150 years ago. Any rebuilding should be a reflection not of an old France, or the France that never was — a non-secular, white European France — but a reflection of the France of today, a France that is currently in the making. ‘The idea that you can recreate the building is naive. It is to repeat past errors, category errors of thought, and one has to imagine that if anything is done to the building it has to be an expression of what we want — the Catholics of France, the French people — want. What is an expression of who we are now? What does it represent, who is it for?,’ he says.” But why rebuild Notre Dame at all if you want to expunge the past? Just raze it to the ground and build a new, coherent structure that captures this contemporary idealism in every detail, inside and out.

Is the Palace of Westminster next? It caught fire “40 times between 2008 and 2012 alone.”

In other news: The Pulitzer winners have been announced. Richard Powers won the fiction award for Overstory, David Blight won in history for his account of Frederick Douglass, and The Washington Post book critic Carlos Lozada won in criticism.

The novelist Gene Wolfe has died: “Wolfe’s publisher Tor, when announcing the news on Monday, described him as a ‘beloved icon’. ‘He leaves behind an impressive body of work, but nonetheless, he will be dearly missed,’ said the publisher, pointing to The Book of the New Sun’s ranking in third place in a Locus magazine poll of fantasy novels – behind only The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit.”

Michael Holroyd writes about how his first novel went unpublished in England because of a lawsuit threat…from his father: “As you know I work in a firm with a staff of several hundreds…In the circumstances – for my sister’s sake and my own – I must do everything to prevent this book being published anywhere till we are dead, and I am prepared to take whatever steps that are necessary legal or otherwise.”

Was the art forger Eric Hebborn murdered by the mafia? Unsurprisingly, filmmakers working on a TV drama of his life think so.

Need a vacation? Rent Claude Monet’s three-bedroom home in Northern France.

Isaac Chotiner on the art of the interview: “One frustration I’ve had reading interviews is that they feel really edited to me. They’d be really good, but they didn’t feel like a real conversation. I’ve been fortunate enough to have some really good editors, who push me both before and in the editing process to make sure that [the interviews] reflect the actual conversation, because that makes them more interesting and less artificial. I also think it’s a more honest representation of the conversation itself.”

Essay of the Day:

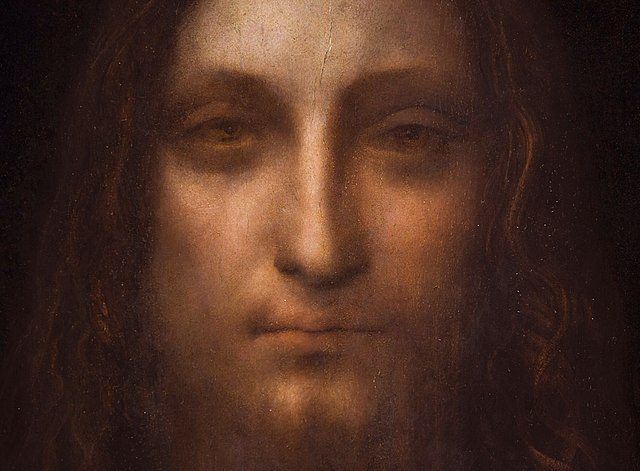

In Vulture, Matthew Shaer writes about how Salvator Mundi went from a $1,000 auction piece to Leonardo da Vinci’s $450-million final work. It required extensive restoration. Was it over-restored?

“In November 2006, when Modestini retook possession of the Salvator Mundi, she had a better sense of the work that lay ahead of her. ‘There were passages that were unusually well preserved,’ she told me, citing the blessing hand and the tumbling curls on the left side of Christ’s head. ‘But you also had passages’ — such as the right-side curls and that ‘clown’s mask’ on the face — ‘that were extremely damaged.’

“Very few 500-year-old paintings have survived to the present day in perfect condition. ‘The vast majority,’ says Brian Baade of the University of Delaware’s art-conservation department, ‘have required restoration during their long lifetimes.’ Sometimes restoration is just a matter of removing surface coatings that have degraded or darkened. Often it requires more substantial work, including in-painting, which fills in damaged areas. ‘Conservators,’ Baade said, undertake this technique ‘not to trick the viewer but to reintroduce a sense of coherence and harmony, which is lost when damage remains visible.’ And yet restoration, like authentication, is a subjective science. Two hundred years ago, it was common for restorers to overpaint pictures so heavily that the original image all but disappeared; some schools of restoration, particularly in Europe, have advocated a minimalistic approach that allows viewers to distinguish between the original artwork and the in-painting without having to hold a black light to the canvas.

“In restoring the Salvator Mundi, Modestini, who says she ‘tries to imitate the original as closely as possible,’ would be charged with bringing a badly damaged painting back to life while conserving what remained of the original draftsmanship. And if her efforts on the painting happened to yield insight into its authorship, so much the better.

“In an essay published in 2015, Modestini details the long process of restoring Christ’s face, which gave her no shortage of trouble — a previous clean had stripped away the 20th-century overpaint while revealing areas of abrasion around the eyes and chin. ‘The ambiguity between abrasion and highlight made the restoration extremely difficult, and I redid it numerous times,’ she wrote. Equally time-consuming was the ‘muddy background.’ To fix it, she added ‘a glaze of rich warm brown,’ then more layers of paint, distressing the paint between layers ‘to make it look antique … The new color freed the head, which had been trapped in the muddy background, so close in tone to the hair, and made a different, altogether more powerful image.’

“About a year into the restoration process, Modestini was repairing some damage to Christ’s lip when she noticed a set of color transitions that she described to me as ‘perfect. Just the way the paint was handled — no other artist could have done that.’ In 2006, the Louvre had published a book called Mona Lisa: Inside the Painting, which included high-resolution close-ups of the subject’s features. ‘I was studying her mouth, and all at once, I could no longer hide from the obvious,’ Modestini later wrote. ‘The artist who painted her was the same hand that had painted the Salvator Mundi.’ Already Modestini had used intact portions of the painting, such as the corkscrews of hair, to inform her in-painting of destroyed ones. After her epiphany about the authorship, she no longer was just restoring a Renaissance painting — she was restoring a Leonardo. She studied how he had handled certain passages or transitions in analogous works, such as the Mona Lisa and Leonardo’s other masterwork, St. John the Baptist. Her work was almost ontological in nature; by relying on Leonardo’s work to restore the painting, was she uncovering a Leonardo or bringing it into being?

“No specific technique used by the Salvator Mundi’s restorers was particularly unusual. What sets the painting apart, one prominent art-world figure told me, is the scale of the restoration. ‘You’ll get defenders of the painting who will say, ‘Look at a work like [Hans] Holbein’s The Ambassadors. That had loss too, and it was restored and repainted, and now it’s hanging in a museum!’ ’ the source said. ‘Well, yes, but that loss was 5 to 10 percent of a very large painting. With all due respect to the immense talents of Dianne Modestini, the Salvator Mundi was a much smaller picture, and the amount of required intervention was proportionally higher. And that should be a key area of debate: Where does conservation become invention?’”

Photo: Tea harvest

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments