Losing Cambridge’s Lawns, What Freud Got Right, and Orwell’s Women

Good morning. Wilfred McClay writes about what Freud got right in The Hedgehog Review: “Freud himself understood that he was not really a scientist, and that ‘social philosophy and cultural critique’ were always the focal points of his deepest interests. What Freud was really after was a fresh ‘interpretation of culture,’ one that would then lend itself to the transformation of culture. Science was valued not for its capacity to ascertain unassailable truth but for its power as a critical weapon, a cultural solvent capable of dissolving the illusory hold of such oppressive forces as religion, social hierarchy, and bourgeois morality. Freud’s youthful abandonment of law and politics in favor of science was not, as the historian Carl Schorske and other have argued, an ‘Epimethean’ retreat, in which Freud elected to ‘eavesdrop’ on Nature’s “eternal processes” rather than seek to change the world. It was better understood as a change in tactics in pursuit of that same end.”

George Orwell’s life with women: “Married life offered plenty of examples of the level of detachment that Orwell was capable of maintaining in the course of his daily existence. Eileen once went out for the night leaving her husband’s shepherd’s pie cooking in the oven and a dish of jellied eels for the cat and came back to find that Orwell had eaten the jellied eels as the pie lay quietly incinerating. If this was only exasperating, then there were times when it gestured at a kind of emotional severance. Eileen believed that the difference between Orwell and her adored brother Laurence, who died in the retreat from France in 1940, was that if summoned Laurence would come from the ends of the earth to her side; ‘George would not do that.’”

David Bromwich reviews the second volume of Robert Frost’s letters, which are “never tedious for all the chat and twice as entertaining for the clarity of the notes.”

In search of Solomon’s Armageddon: “James Henry Breasted, the founding director of the newly-established Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, had been wanting to dig at Megiddo, the site of biblical Armageddon, ever since June 1920 . . . Breasted was particularly interested in recovering the remains of two cities out of the many that lay, one on top of another, within the ancient mound. One was the city that had been captured by Thutmose III. The other was Solomon’s, which that ancient king had reportedly fortified during the 10th century BC, according to the Hebrew Bible.”

Take a walk . . . alone . . . without your phone or smart watch: Walking is increasingly mediated by technological gadgets worn on wrists or gripped in hands. We spend an increasing amount of time ‘screening’ the world – taking in most of life through a contracted frame that captures objects of immediate interest. To live with eyes on the screen is to be attached, stuck in the frame, taking in what is presented to us and re-presented to us again. But representation – even in fine-grained pixilation – is not experience. To experience is to perceive. When we look at a screen, we might see something, but we don’t perceive. To live life through representations is to live passively, to receive rather than to experience. It is also, we fear, to live the life of a follower. Instead of asking What do I see? How might I tell you? we are told instead how to see, and often what to feel – much of which is determined by algorithm.”

Essay of the Day:

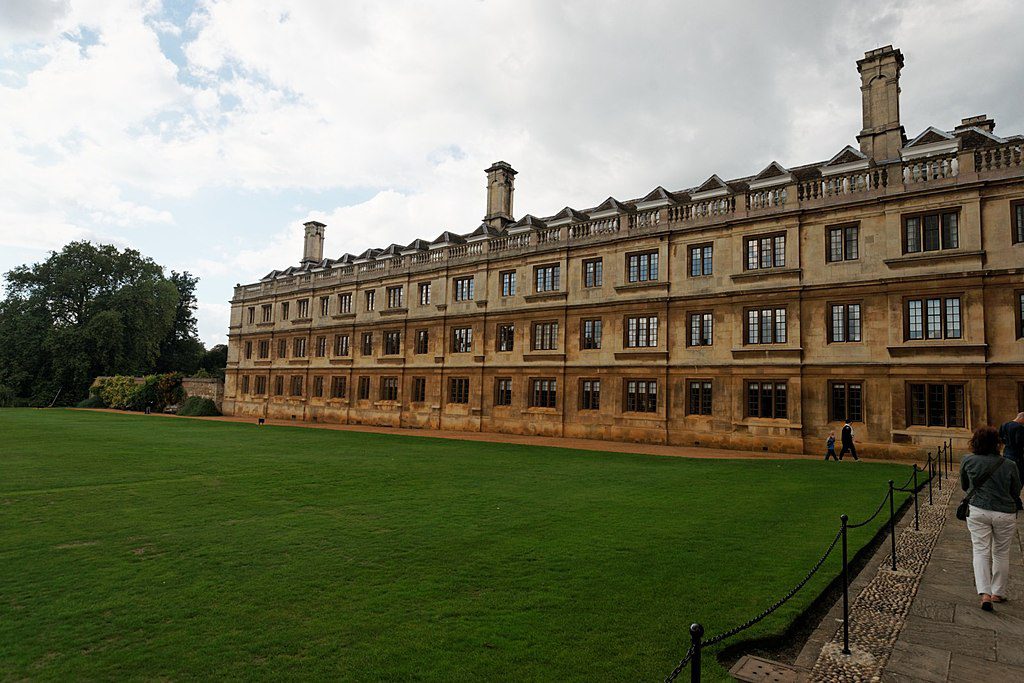

In The Critic, Timothy Mowl complains about the loss of Cambridge’s lawns:

“When I was last in Cambridge on the trail of the Pre-Raphaelites I was doubly affronted, being an Oxford man and an academic, when an officious college porter barked at me to keep off the grass as I stretched to achieve the best angle for a photograph of the Mathematical Bridge at Queens’, which I needed for a lecture. I shouldn’t have been surprised to be so chastised, as Oxbridge is suffused with such traditional hierarchies which serve to enhance that sense of privileged exclusivity. Now all that is to change at King’s on the hallowed turf, preserve only of university dons, in front of the Chapel and James Gibbs’s New Building by the banks of the Cam.

“In a brave ecological move, the college fellows and their gardens committee have decided to turn their vacant lawn into a wildflower meadow, creating, as their head gardener Steve Coghill describes it, a ‘biodiversity-rich ecosystem’. At a stroke, this will alter one of the most celebrated views in the whole of the city and would be like cutting down that sycamore tree in the High at Oxford which gives colour and texture to an otherwise stony thoroughfare.

“The loss of the formal Back Lawn at King’s is symptomatic of the way in which both Oxford and Cambridge have swept away almost all of their historic gardens, opting instead for a minimalist treatment of lawns and suburban flower borders where once greensward was dotted with cypress trees and enriched with parterres, living sundials, mounts, arbours, canals and garden houses. Added to this is the disappearance of many of the private fellows’ gardens on the west bank of the Cam, which have been subsumed within later building.”

Photo: Tel Megiddo

Poem: Paul Valéry, “The Cemetery by the Sea” (translated by Nathaniel Rudavsky-Brody)

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments