Frank O’Hara’s Conservatism

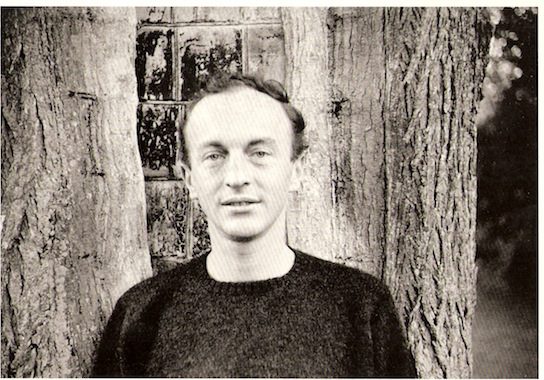

Frank O’Hara (1926-1966) is one of those post-World War II poets who—like almost all post-World War II poets—would seem to be anything but a conservative.

For starters, he was gay and proud of it. He flaunted his sexuality in his poems and was sometimes impatient with homosexuals who were more closeted.

His interests in painting and literature were—at least on the surface—neither particularly traditional nor Western. His professional interest in American Abstract Expressionism as a curator at the Museum of Modern tells us little. He disliked Andy Warhol and Pop Art, but he also disliked T.S. Eliot and was interested in novelists and poets whose work attacked social norms, such as Jean Rhys, Jean Genet, and Alain Robbe-Grillet.

While in the Navy, he often read The Daily Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party in the United States, and he occasionally hung out with the folks from Partisan Review in New York.

His political views, however, are difficult to deduce from these associations. As Jeff Encke points out, O’Hara’s politics were “complex.” He loved Russian music and literature and seemed to be sympathetic to Communism as a youth but came to dislike the Soviet government. Encke:

His views of people were not based on nationality or ideology, but more on individual achievement. On the one hand, for instance, “The Communist Manifesto” was one of his favorite works, while, on the other hand, in his 1963 poem “Answer to Voznesensky & Evtushenko,” he quickly dismissed the progeny of that influential work:

oh Tartars, and how many

of our loves have you illuminated with

your heart your breath

as we poets of America have loved you

your countrymen, our countrymen, our lives, your lives, and

the dreary expanses of your translations

your idiotic manifestos

As Encke notes, one of the things that stands out in O’Hara’s prose–as it does in Russell Kirk’s–is his distaste for ideology, particularly as expressed in “idiotic manifestos.” He wrote a number of mock manifestos that ridicule the pretension of such statements. In “Personism: A Manifesto,” for example, O’Hara needled poets preoccupied with the social benefits of their work:

But how can you really care if anybody gets it, or gets what it means, or if it improves them. Improves them for what? For death? Why hurry them along? Too many poets act like a middle-aged mother trying to get her kids to eat too much cooked meat, and potatoes with drippings (tears). I don’t give a damn whether you eat or not. Forced feeding leads to excessive thinness (effete). Nobody should experience anything they don’t need to if they don’t need poetry bully for them, I like the movies too. And after all, only Whitman and Crane and Williams, of the American are better than the movies. As for measure and other technical apparatus, that’s just common sense: if you’re going to buy a pair of pants you want them to be tight enough so everyone will want to go to bed with you. There’s nothing metaphysical about it. Unless, of course, you flatter yourself into thinking that what you’re experiencing is “yearning.”

This is not to say that art does not have social benefits or communicate certain truths about life, but that is not its first function according to O’Hara. Its first function is to be “not boring,” as he put it in an interview with Edward Lucie-Smith.

In another mock manifesto, “How to Progress in the Arts,” O’Hara and painter Larry Rivers parody progressive manifestoes like Andre Breton and Leon Trotsky’s “Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art.” O’Hara found surrealism’s tool of automatic writing freeing. At the same time, he bristled at Breton’s dogmatic political views and scoffed at the idea that automatic writing was entirely automatic or that it revealed some collective unconscious.

In fact, O’Hara regularly defended the idea of the individual genius and argued that a temporary beauty (though he later became uncomfortable with this word) that engages our attention, not political change, is the proper end of art. Individual innovation is one of the touchstones of all great art for O’Hara. I wrote elsewhere:

This presupposition underlies much of his critical evaluation of artists in his reviews for ArtNews between 1953 and 1955. O’Hara praises Juan Gris (1887-1927), for example, as one of “the great individualist of the [Cubist] movement” and writes that “it seems that he would have painted the way he did whether there had been a movement or not.” He praises Grace Hartigan (then George Hartigan) for her highly individual paintings, which “seem to be a means of dealing with experience on her own terms and insisting on her own meanings”… In his review of Bennett Bradbury (1914-1991), O’Hara dismisses Bradbury’s commitment to one style as merely boring. He writes, for example, that his paintings “are academic; uniformity of execution and similarity of composition make it possible for him to maintain the same level throughout the show, but it is rather like looking at just one picture.”

O’Hara associates uniformity with “academic” art here (which was shorthand for more conservative art at the time), but uniformity was also an aspect of Andy Warhol’s paintings and social realism, both of which he disliked.

While some on the left see art as a product of mere social forces, O’Hara believed that poetry was a “testament” of the self and that love was real. Drawing from his Catholic schooling and James Joyce’s aesthetics, in some poems he expressed the view that the artist was as a sort of Christ-figure who suffers to renew our experience of the world.

O’Hara’s relationship to the Western tradition is also much more complex than it is often presented. Because his work was innovative and came into fashion at the university at the same time as critical theory, it has often been characterized as exhibiting a sort of proto-Derridean deconstruction of meaning.

Granted, O’Hara’s poems often do seem to be nothing more than mere “surface” play. But while he certainly critiques the fixity of morals and meaning (as does Wallace Stevens), he also frequently deals with friendship, death and love. His love poems, for example, avoid sentimentality while still expressing a deep affection for someone else with a naturalness that make them particularly effective. In “Poem V (F) W,” he writes:

you were walking down a street softened by rain

and your footsteps were quiet

and I came around the corner

inside the room

to close the window

and thought what a beautiful person

and it was you

no I was coming out of the door

and you looked sad

which you later said was tired

and I was glad

you had wanted to see me

and we went forward

back to my room

to be alone in your mysterious look

The precariousness and thrilling surprise of love is captured as two individuals move in various directions (“down,” “around the corner,” “out the door”) with one misreading the other (not “sad,” just “tired”), overcoming these potential setbacks to go “forward / back” to the bedroom. O’Hara did not believe in divine love, and his poems show that human love often causes more pain than anything else. Yet, love remained for him one of the great realities of life.

Regarding tradition, it’s true that O’Hara disliked Eliot, but it was more Eliot’s odd pronouncements against the Romantics and John Milton (whom O’Hara loved) than Eliot’s early poetry that annoyed him. Like Eliot, he valued tradition, though differed regarding who counted as worthwhile. William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound were, of course, models for him, but so were Whitman, Stevens, Antonio Machado, Boris Pasternak, Rainer Maria Rilke, René Char, and even John Donne, William Wordsworth and Lord Byron.

None of this, of course, makes O’Hara either a libertarian or a conservative. Those terms don’t mean the same thing now as they did during O’Hara’s lifetime, and even then, no one term—from the left or the right—clearly applied.

What it does show—though very incompletely—is how truths or partial truths about life sometimes associated with libertarianism or conservatism can be found in unexpected places, where they are defended with a good deal of wit and originality, should we care to look.

Prufrock is a daily newsletter on books, art and ideas, edited by Micah Mattix. It contains links to the best reviews and most worthy literary news items, a daily essay with relevant responses, and a little bit of literary smack. Best of all, it’s free! Subscribe today.

Comments