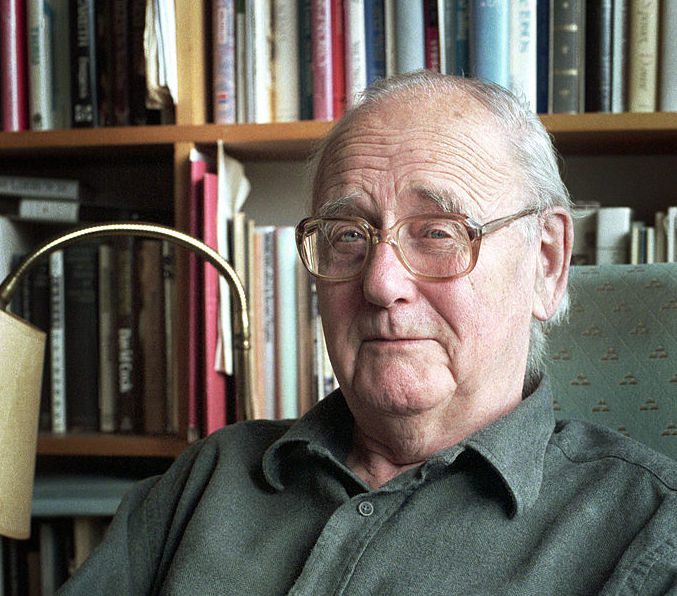

Frank Kermode Reviews

The British critic Frank Kermode wrote “several hundred reviews” for weeklies and monthlies during his lifetime. He regretted them all, he said: “It is, once one begins, all too easy.” How did Kermode start reviewing and was it as bad for his career as he claimed? Stefan Collini tackles these and other questions in a piece for the London Review of Books:

The appearance of Romantic Image changed Frank’s life, and with surprising speed. Just as Miller commissioned his first review from him in its wake, so did Encounter, Frank’s other main perch for the next few years, his first piece appearing in the issue of December 1957. Commissions from other periodicals followed. After moving to Manchester in 1958, he began reviewing regularly for the Manchester Guardian. By the end of the 1950s, ‘Frank Kermode’, reviewer extraordinaire, the go-to man for readable, informed thoughtfulness on any literary subject, was well and truly launched.

But still there were gaps in the story. In a short piece of intellectual autobiography written in 1981, not all of which was reused in his memoir, Not Entitled, 14 years later, Frank paid tribute to the somewhat surprising role of John Butt, professor of English at Newcastle during his time there: ‘He launched [his colleague Peter] Ure and myself on our career as reviewers – which causes me to reflect that in thirty-odd years I have written several hundred reviews, an example I would strongly urge the young not to follow. It is, once one begins, all too easy. Somebody mentioned me to J.R. Ackerley at the Listener, and so was born the journalist who has wasted so much of my time.’

This strikes that note of mock sorrow Frank cultivated when setting aside various episodes in his life, while at the same time not altogether disguising the pride he evidently felt in his journalistic facility and accomplishment. The passage seems to suggest that there were two stages in his temptation and fall: Butt gives him the first nudge down the slope, and then his descent picks up speed when he falls into the clutches of a notorious journalistic roué. It has in miniature the shapeliness of so much of Frank’s autobiographical writing, but on closer examination it does seem slightly odd. For one thing, the reviewing opportunities that Butt was able to put in the way of his two junior colleagues amounted to nothing more satanic than an occasional short notice for the scholarly journal he edited, the same Review of English Studies where Frank wrote that early review – obviously, I now saw, commissioned by Butt. Still, most young academics would see this as an entirely normal and respectable professional activity, hardly the beginning of a debauch. It’s harder to know what to make of the reference to ‘Joe’ Ackerley, the legendary literary editor of the Listener from 1935 to 1959. In the late 1940s and early 1950s the Listener carried very few freestanding book reviews: it had a ‘Books Chronicle’ which consisted of short mostly unsigned paragraphs. Frank may have contributed some of these, but their anonymity means that they could hardly have been a route to a public profile as a reviewer. A little rummaging in the online archive revealed that no signed full-length review by him appeared there before 1967.

This started another hare running in my mind. I knew that John Wain had been Frank’s colleague in the English Department at Reading until the success of his novel Hurry On Down enabled him to go freelance in 1955. But Wain had already started to become a figure in the literary world in 1953 as a result of editing the BBC Third Programme magazine, New Readings, where he commissioned talks and readings from a variety of his old buddies, notably members of the group shortly to be christened ‘the Movement’, Philip Larkin and Kingsley Amis among them. Frank had once told me Wain helped give him an entrée into broadcasting, perhaps introducing him to the long-serving Third Programme producer, Donald Carne-Ross, and although such casual reminiscences are prone to elide important details, it only took a little more digging to reveal mentions in the Listener of several broadcasts by Frank from 1955 onwards.

That he had done such talks was not in itself news to me, but I started to feel that I had previously underestimated the importance of these Third Programme gigs in helping to establish Frank’s name and in developing his confidence about addressing non-specialist audiences.

In other news: Angela Alaimo O’Donnell takes the leadership of Loyola University Maryland to the woodshed for removing Flannery O’Connor’s name from a building.

Sophie Pinkham reviews Sophy Roberts’s The Lost Pianos of Siberia: “In 1774, Catherine the Great ordered a square piano anglais — then the hot new instrument — from England. By the beginning of the 19th century many affluent Russian households had pianofortes, and piano lessons and recitals were in high demand. Russia eventually produced outstanding classical composers and musicians, among them pianists like Anton and Nikolai Rubinstein and Sergei Rachmaninoff. The 1917 Revolution scattered and destroyed many of Russia’s pianos, but the Soviets later brought affordable pianos, as well as musical education, to people who could not otherwise have afforded to touch such an instrument. As Russians and other travelers moved east — first as explorers, traders and colonizers and later as political exiles and prisoners — their musical instruments went with them. Anna Bering, the wife of the Danish maritime explorer Vitus Bering, brought a clavichord from St. Petersburg to the Sea of Okhotsk in the 1730s, traveling 6,000 miles by sleigh, boat and horse, and then brought it back again. Maria Volkonsky, the famously devoted wife of one of the Decembrists, brought a piano when she joined her husband in exile in Irkutsk, soon dubbed the ‘Paris of Siberia.’”

Pete Hamill has died. He was 85.

Tom Shippey reviews a new history of the Vikings: “Over the last forty years, academics have tried, without much success, to superimpose the idea of the Vikings as peaceful traders on the berserkers-and-horned-helmets tradition. There is little disagreement about the events of the Viking Age or its timeline, stretching from 8 June 793 (the unexpected raid on Lindisfarne) to 25 September 1066, when King Haraldr Harðráði, ‘Hard-Counsel Harald’, died at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. As Neil Price points out, all this should be seen as protohistory rather than history. The Vikings themselves couldn’t write, except for short runic inscriptions carved in wood or stone, and had no dating system beyond ‘the fourth year of King Olaf’ and so on. Royal succession was the only way to mark time. The sequence of events we refer to as the Viking Age was put together from the accounts of their many victims, from Ireland to Byzantium. Price’s book, however, centres on ‘what made [the Vikings] tick, how they thought and felt’.”

Did the French painter Jean-Francois Millet influence the work of modern artists like Salvador Dalí? Probably not, but it doesn’t matter, Brian Allen argues. He’s a marvel nonetheless.

What does the attempt to eradicate smallpox teach us about COVID-19? Kate Womersley reviews two new books: “It took until 1980 for the WHO to announce that smallpox was over, two centuries after a vaccine was invented. It was the first and only disease ever to have been eradicated. The world now waits for another vaccine. News outlets portray this search as a race between competing laboratories. Yet as the history of smallpox shows, if collaboration, efficient distribution, equitable access and the fostering of public trust are mere afterthoughts to the science, the vaccine will fail. We can only hope that history repeats itself with a Jennerian discovery in the months ahead, but it will be just the beginning of the work required to keep us safe.”

Photos: Aftermath of the Beirut explosion

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments