Eliot and Emily

T. S. Eliot—the poet of impersonality—had a complicated relationship to his letters. In a lecture at Yale on “Letters of English Poets,” Eliot said that we “want to confess ourselves in writing to a few friends,” but “we do not always want to feel that no one but those friends will ever read what we have written.” Is this how Eliot thought of his letters to Emily Hale? Almost certainly not, Paul Keegan writes in the most exhaustive treatment to date of Eliot’s letters to Hale, which were opened to researchers earlier this year:

Eliot’s considerable correspondence with Hale had begun in October 1930, and in 1933 they were still in the foothills. Describing his Yale lecture – she was teaching in California – he added: ‘If you don’t see my private joke in talking about how a poet should write letters, no one will.’ The joke is perhaps that the lecture is unaware of Eliot’s epistolary life (‘Love letters are monotonous; the recipient of the letter should be a mature friend’) – and that it conceals how hard he is thinking about the subject.

Put differently: here are 1131 letters (eight thousand pages or scans, including envelopes and enclosures), deposited by Emily Hale at Princeton University Library in 1956, not one of which Eliot wrote in the hope of it being read by strangers. Under embargo for fifty years after Hale’s death in 1969 – she outlived Eliot by four years – they were unsealed in January 2020 and can now be consulted in situ in Princeton. A selection is being prepared by John Haffenden, to be published next year. ‘A good deal of publicity is possible without publication (in print),’ Eliot wrote sceptically in his posthumous ‘statement’ about the correspondence, opened at the same time as the Princeton deposit.”

* * *

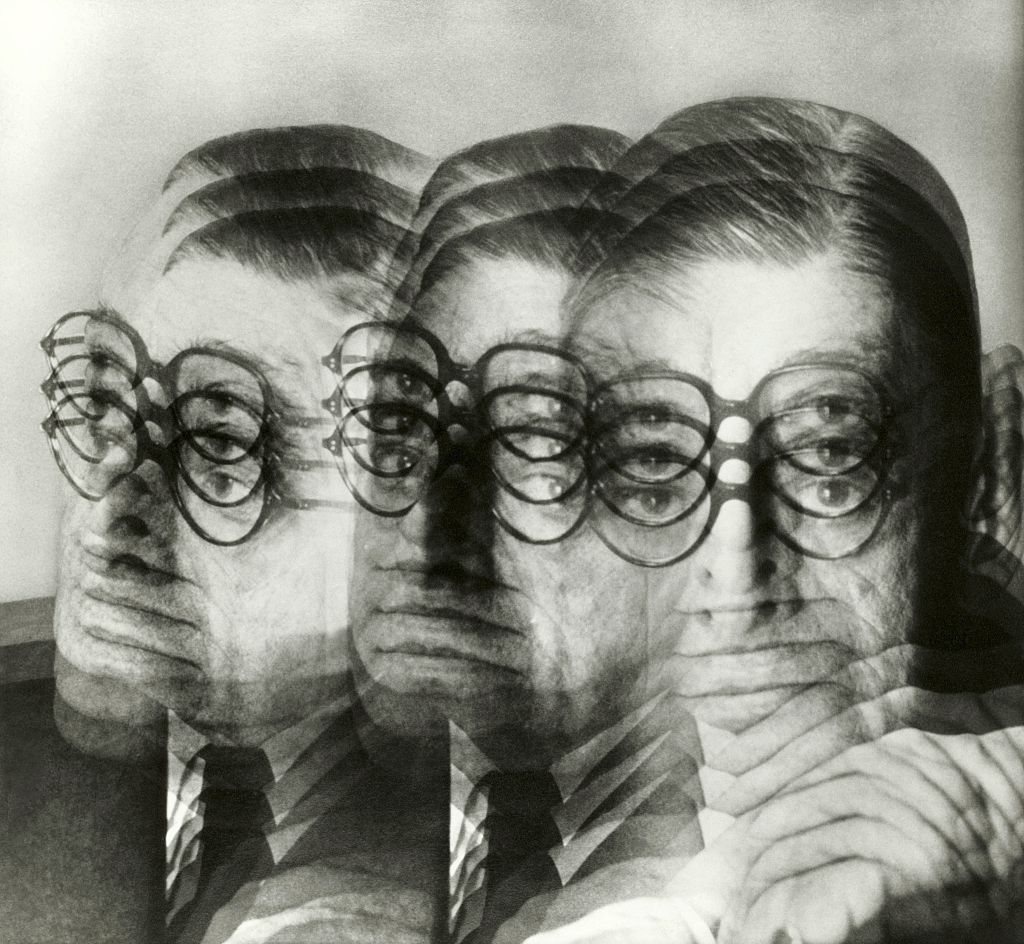

Eliot’s letters to Hale are compositions, usually long, almost invariably typed, with only the occasional faltering of phrase or finger, and few erasures or marginal additions. Eliot didn’t keep carbon copies of private letters, as he reassured Hale at the start, ‘however strange such things will look to me in type’. They are mostly typed on headed paper (‘The Criterion’, ‘Faber & Faber’, ‘The New Criterion’, ‘The Virgil Society’ – any headed paper he could get his hands on, except when travelling). Early on they were written in the office. As with Kafka’s heroic epistolary feats in respect of women he didn’t marry – five hundred letters to Felice – the life of the letters to Hale is played out against office gossip, the views from windows, ‘the noise of typewriters’, the business of the day. If, as Eliot told her, a letter is the photograph of a moment (and a different hour would produce a different light, a different letter), then his early efforts are studio portraits: ‘My room is in cream yellow with bookcases (for review books etc), two chairs and a desk and an armchair, a green carpet (to come) and an electric stove, very high looking down over Woburn Square.’

In January 1931 he describes his working day: ‘On Friday morning when I arrived the flamboyant Mr Alfred A. Knopf of New York (Inc.) with brilliant tie and stickpin was filling the whole room talking to Morley, and then he collared me, and wasted most of the morning jawing about nothing.’ Eliot’s ear is cocked, recalling earlier instances of how a name can betray its bearer. Alfred A. Knopf, with his publisher swagger, has the ‘jaw’ and superbia of Apeneck Sweeney, but his secret sharer is J. Alfred Prufrock, who filled no room, whose ‘modest’ necktie was ‘asserted by a simple pin’. The animus is compressed, even as the scene ripples outwards. (This was the same Knopf who a decade earlier had passed on the chance of publishing The Waste Land in America.) Eliot’s own words echo in his mind. This had been a feature of his epistolary economy before Hale. But there is a recurrent and unemphatic recourse throughout the letters to earlier usages, which are also reflections on an earlier self.

Speaking of Eliot, the prize named after him has announced the shortlist for this year’s award. The books are as “urgent” as they are artful, we’re told.

In other news: Craig Raine revisits the work of the “forgotten” but remarkably modern Arthur Hugh Clough: “In the 1970s, my wife and I went to the English Cemetery in Florence – a small, crowded island in the middle of a busy road. At first, we couldn’t find Clough’s grave. We persisted because we knew it was there. And eventually we located the tiny, tilted headstone, obscured, almost beyond the pale, right under the hedge that marked the cemetery’s circular boundary. Let this stand for Clough’s standing as a poet . . . Clough is a realist enquiring into the nature of feeling, though he favours not denunciation, but comedy and tender deflation. His poetry shows a nimble ironist who cut genuine pathos with bold deadpan bathos – they co-exist.”

I have a soft spot for polka and zydeco, and I would like to learn to play the accordion one day. It is a beautiful instrument and, as Laura Stanfield Prichard writes, an amazing example of technological innovation and cross-cultural exchange: “The earliest forms of the accordion were inspired by the 1777 introduction of the Chinese free-reed sheng (bowl mouth organ) into Europe by Père Amiot, a Jesuit missionary in Qing China. Amiot entertained Beijing listeners by playing harpsichord versions of Rameau’s music, including Les sauvages (later part of Les Indes galantes). His introduction of the sheng set off an era of experimentation in free-reed instruments such as Anton Haeckel’s Physharmonika, a bellows-operated reed organ (Vienna, patented 1818), and Friedrich Buschmann’s mouthblown “Handäoline” (Berlin, patented 1822). Two of Haeckel’s instruments from 1825 can be seen in the Vienna Technical Museum. The Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg holds Europe’s largest collection of early German free-reed instruments, accordions, and harmonicas.” Take that, haters of cultural appropriation!

Why are the same artworks stolen multiple times. It’s often not about money, Riah Pryor reports: “One of the key reasons seems to be criminal prestige: stealing a famous painting can boost a thief’s reputation within a network and present other opportunities. A valuable work of art can also be used as a form of collateral for future deals or to transfer value across borders . . . In other examples, it appears that anticipating the authorities catching up with them is exactly the reason why such prime works are appealing to criminals. ‘One thing I’m seeing more of is the use of such stolen works as a bargaining chip for [reducing] sentences,’ says Robert Read, the head of art and private clients at Hiscox.”

The real Richard III: “Richard III was king of England for only twenty-six months (June 1483 to August 1485). Yet thanks in large part to Shakespeare’s vivid depiction of him as a charismatic villain, he is one of the best-known monarchs and most controversial figures in English history. His critics claim, rightly, that he was a bully, a thief, and a murderer who usurped the throne by killing the ‘Princes in the Tower’ (the boy-king Edward V and his brother, Richard, Duke of York). By contrast, his defenders in the Richard III Society (founded in 1924 as the Fellowship of the White Boar) believe, also rightly, that his vices were exaggerated by Tudor propagandists and that he was a pious Catholic, a courageous soldier, and a conscientious ruler. Richard’s admirers were thrilled in 2013 when archaeologists unearthed what were identified as his bones in a Leicester parking lot on the former site of the Greyfriars Church, where he was buried in 1485. Shakespeare made much of Richard’s physical disabilities, portraying him as hunchbacked, with a withered arm and one shoulder higher than the other. His bones (if they were his: Michael Hicks, in his excellent new biography, Richard III: The Self-Made King, seems rather agnostic about that) confirmed that he was short, slightly built, and did indeed suffer from curvature of the spine (scoliosis), but had no withered arm. He was also said to have been fidgety, continually biting his lip and repeatedly pulling his dagger halfway out of its sheath and putting it in again.”

The first of 59 recently discovered sarcophagi has been opened: “On Saturday, October 3, archaeologists from Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities opened a sealed, roughly 2,600-year-old sarcophagus as a crowd of onlookers watched in anticipation. Lifting the lid, the researchers revealed a mummy wrapped in ornate burial linen; more than two millennia after the individual’s interment, the cloth’s inscriptions and colorful designs remained intact. Per a statement, the newly unveiled coffin is one of 59 sealed sarcophagi unearthed at the Saqqara necropolis—a sprawling ancient cemetery located south of Cairo—in recent months. Found stacked on top of each other in three burial shafts of differing depths (between 32 and 39 feet each), the coffins date to Egypt’s 26th Dynasty, which spanned 664 to 525 B.C. Researchers think the wooden containers hold the remains of priests, government officials and similarly prominent members of ancient Egyptian society.”

Photos: Winners of the 2020 Nikon Microphotography Competition

Comments