Death in Longfellow

Death was ever present in nineteenth-century America. How did Longfellow deal with it? Nicholas A. Basbanes explores:

Although the years of their marriage were overwhelmingly idyllic, the death of Little Fanny, as the child was called, from a vaguely diagnosed ‘congestion on the brain’ 18 months later left both parents devastated, prompting Henry to write the poignant poem of loss and grief ‘Resignation’(1850). Fanny expressed her feelings privately in a chronicle she kept of her children’s daily activities. ‘My courage is almost broken,’ she confided, and described how watching her daughter slowly ‘sinking, sinking, away from us’ was a period of ‘agony unutterable.’ She told of holding the child and hearing ‘the breathing shorten, then cease without a flutter,’ whereupon she ‘cut a few locks’ of hair from the child’s ‘holy head’ and had her placed in the library ‘with unopened roses about her, one in her hand, that little hand which always grasped them so lovingly.’ Henry recalled the loss with equal tenderness: ‘For a long time, I sat by her alone in the darkened library. The twilight fell softly on her placid face and the white flowers she held in her little hands. In the deep silence, the bird sang from the hall, a sad strain, a melancholy requiem. It touched and soothed me.’

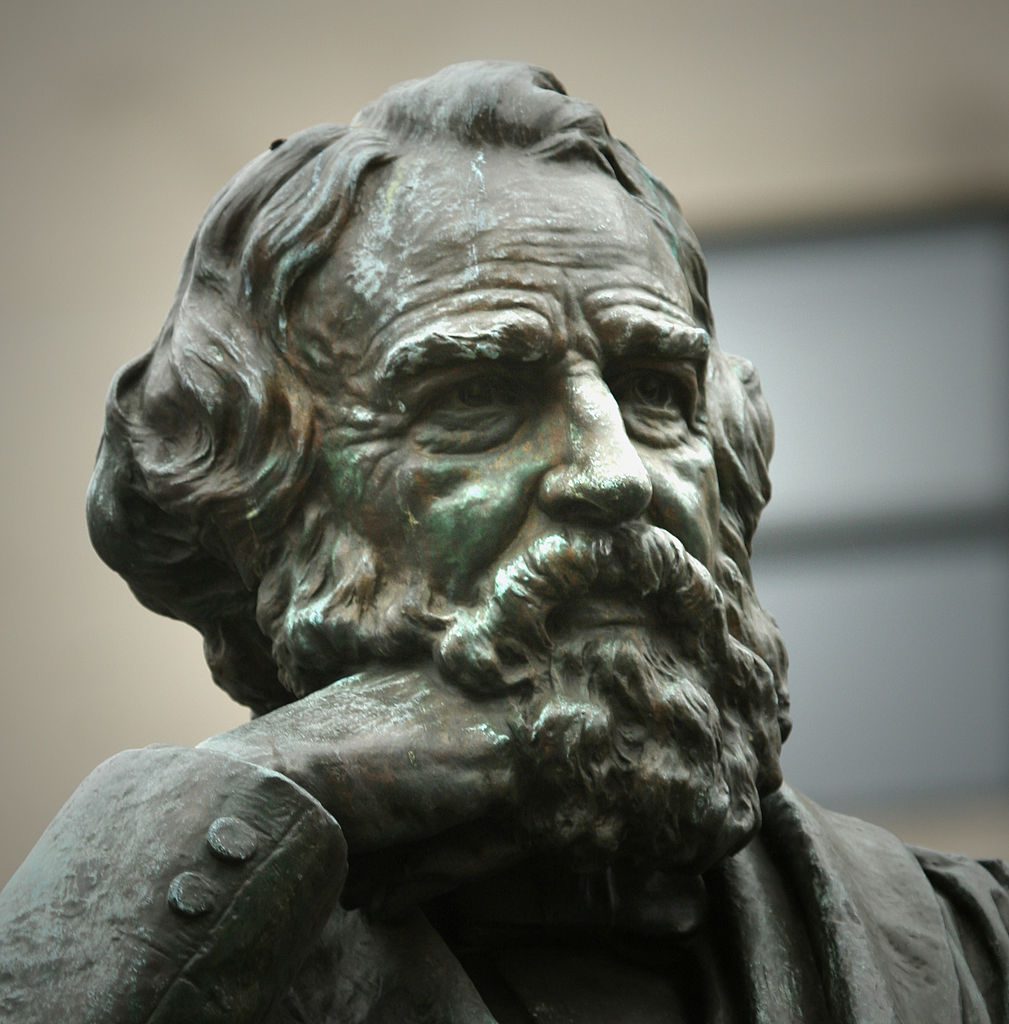

Everyone, at some point, must contend with the loss of loved ones from natural causes, and Fanny and Henry were no exception, their response to these sad events unfailingly expressed with grace and dignity. Nothing in their experience, however, could have prepared them for what transpired on July 9, 1861, a hot summer day when the family normally would have been enjoying the sea breezes at their summer retreat in Nahant, but were home so Fanny could be close to her dying father in Boston. After returning from a morning by Nathan Appleton’s bedside, she decided to cut some locks of hair from her seven-year-old daughter, Edith. While sealing a snippet in an envelope with wax from a lighted candle, her hooped muslin dress caught fire, setting her ablaze in an instant. Trying desperately to snuff out the flames with a small rug, Henry suffered burns on his hands and face, leaving scars that he would hide in the years ahead with the long white beard that became so familiar to his millions of admirers. Fanny survived the night, her horrible pain at length lessened by the arrival of some ether, but the injuries were too severe, and nothing further could be done. Her demeanor in these final hours was described by those in attendance as ‘perfectly calm, patient and gentle, all the lovely sweetness and elevation of her character showing itself in her looks and words.’

Henry was inconsolable at first, but there were several young children who needed him now more than ever. ‘I have never seen any one who bore a great sorrow in a more simple and noble way,’ the Boston author John Lothrop Motley reported in a letter to his wife. ‘I hope he may find happiness in his children.’ Describing his state of mind to the writer George William Curtis, who had written a moving letter of condolence, Longfellow apologized for being unable to write a fuller response. ‘I am too utterly wretched and overwhelmed,—to the eyes of others, outwardly calm; but inwardly bleeding to death.’

Over time, Henry would be productive in numerous ways, a singular achievement being his translation into English of all three canticles of Dante’s Divine Comedy, the first American to do so, and to this day greatly admired for its accuracy and fidelity to the original text. On the eighteenth anniversary of Fanny’s death, he wrote a sonnet he called ‘The Cross of Snow,’ an extraordinary poem of loss and grief that remained unpublished during his lifetime, and gave me the title for the book I wrote about his life and his work.

In other news: If you’re in the market for a Cold War missile site and bunker, there’s one available in North Dakota.

Wine windows return in Florence: “As institutions around the world devise new ways of staying safe during the COVID-19 pandemic, restaurants in Florence, Italy, are making creative use of an architectural anomaly: small “wine windows” embedded in the sides of centuries-old buildings. Though no official list exists, the Wine Window Association of Florence has counted more than 150 buchette del vino, or wine windows, scattered across the northern Italian city. As the organization’s president, Matteo Faglia, tells Business Insider’s Phoebe Hunt, the unique portals were introduced to the Tuscany region as a way for sellers to sell surplus wine to working-class buyers. Often decorated with small wooden doors, the openings are just big enough to stick one’s arm through with a glass of wine in hand.”

A new angle on Lincoln’s statesmanship: “In many ways, Lincoln has almost loomed entirely too largely, since it has now become difficult to get around the acknowledgment of his greatness to discover just what it was that made him great. Jon Schaff’s Abraham Lincoln’s Statesmanship is an attempt to maneuver around that ‘persistent fascination’ and lay out what can be known—and better still, appropriated for modern purposes—about Lincoln’s statesmanship.”

Reconstructing Raphael: “According to a report by the French newspaper Le Figaro, researchers at the University of Rome have used a plaster cast of the artist’s skull to create a 3D reconstruction of his face. This new study on the cast of Raphael’s skull, which was made in 1833, has also helped authenticate the artist’s remains, which reside in the Pantheon and have long been the subject of debate.”

Reading Ruth Watson’s large collection of antiquarian cookbooks may not make you hungry, but there are other delights: “Watson’s books show that even hundreds of years ago, diets were the rage. Thomas Elgyot’s 16th-century Castell of Health gave advice about the effects of different foods and diets “whereby every man may knowe the state of his owne body”. And one 18th-century collection of handwritten recipes includes a ‘powder for the teeth to fasten them and make them white’, and a concoction of herbs and spices, mithridate, treacle and aqua vitae, billed as ‘good against the common plague, but also against the sweating sickness, the small pox, measles and surfeits’ . . . Some dishes are less tempting, with a gammon of roasted badger and a viper soup featuring in one 18th-century book, while a 1653 collection of medical recipes recommends that convulsions are to be treated with the dung of a peacock, and jaundice with powdered earthworms.”

Photo: Zurich

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments