Charles I’s Executioners on the Run in America, Murder and “Where the Crawdads Sing,” and Reading Maugham’s “Ashenden”

Delia Owens’s Where the Crawdads Sing has been a runaway success. Why have critics ignored a 1995 murder of a poacher in Zambia that some witnesses say involved Owens’s husband, Mark, and his son? Laura Miller: “Several sources Goldberg spoke with, including the cameraman who filmed the shooting of the poacher, have stated that Christopher Owens—Mark Owens’ son and Delia Owens’ stepson—was the first member of a scouting party to shoot the man. (Two other scouts followed suit.) Others have claimed that Mark Owens covered up the killing by carrying the body, which was never recovered, up in his helicopter and dropping it in a lake. Whoever pulled the trigger that day, what seems indisputable from ‘The Hunted’ is that, over the course of years, Mark Owens, in his zeal to save endangered elephants and other wildlife, became carried away by his own power, turning into a modern-day version of Joseph Conrad’s Mr. Kurtz—and that while Delia Owens objected, at times, to what was happening, she was either unable or unwilling to stop him or quit him. And despite being set in a different place and time, her bestselling novel contains striking echoes of those volatile years in the wilderness.”

Michael Dirda recommends Maugham’s Ashenden: “Initially published in 1928, W. Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden is usually described as the first modern espionage novel. In reality, it’s a collection of linked stories based on the author’s actual experiences while running spies during World War I. The action opens with Ashenden’s recruitment into the Secret Service by R. — just the initial — and ends in 1917 with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution. While not in the least like a James Bond thriller, Maugham’s golden-age classic is equally compelling in its own way, just right for late summer escape reading.”

William Leith reviews Mark Bowden’s The Last Stone: A Masterclass in Criminal Interrogation: “This is horrible. But it’s a book by Mark Bowden, who wrote Black Hawk Down and Killing Pablo, so it’s compelling: an almost perfect true crime story. Two sisters, aged ten and 12, disappeared from a shopping mall in 1975 and were never seen again. What happened to them was a mystery for 40 years. In The Last Stone, Bowden tells you about two things. He tells you how the mystery was solved, and he tells you what happened to the girls.”

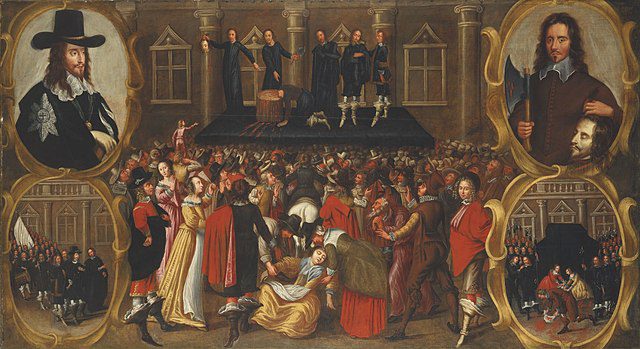

Matthew Jenkinson tells the story of Charles I’s executioners on the run in America. Colin Kidd reviews: “An ocean away, the story of Whalley and Goffe, who escaped to New England, where they were later joined at one point by another regicide, John Dixwell, is for the most part a lighter affair. Although the Puritan colonies of New England were strongly inclined towards the good old cause of parliament and godly reformation, and paid heed to the requests of London for the capture of Whalley and Goffe, their unobtrusive sympathies were with their fellow Puritans. Indeed Matthew Jenkinson presents a delightful comedy of recalcitrance – of delayed, incompetent or misdirected pursuit of the regicides on the part of the authorities in New England.”

Martyn Wendell Jones reviews Chris Arnade’s Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America, a collection of photographs and texts detailing those “left behind” in America’s “depressed post-industrial towns.” The problem with the book, Jones argues, is that it is, in the end, overly simplistic: “By the book’s end, he has seen enough to have reached a conclusion about what needs to happen to guarantee the future of American society and the health of our democracy. ‘We all need to listen to each other more,’ he writes, because ‘our nation’s problems and differences are just too big, too structural, and too deep to be solved by legislation and policy out of Washington.’ Arnade admits it himself: this is a meager conclusion. (He describes it as ‘wishy-washy.’) In view of the indignities and injustices that fill the preceding pages, ‘we need to listen to each other more’ is a letdown that uncharitable readers may interpret as an abdication.”

Essay of the Day:

In The Atlantic, Sarah Zhang writes about how a single male cat destroyed a bird sanctuary of over 220 fairy terns:

“After the victims were found dead—‘decapitated’ and ‘breasts opened’—the residents of a beachside community in Mandurah, Australia, took matters into their own hands. Five locals, along with Claire Greenwell, a biologist at Murdoch University, arranged an overnight stakeout. Another neighbor lent them a mobile home, so they could take turns sleeping at the scene. The target of all this drama? A cat.

“Specifically, a cat who had taken to killing in Mandurah’s bird sanctuary. Mandurah had recently fenced off nesting grounds to attract a vulnerable and cartoonishly adorable native seabird called the fairy tern. Fairy terns don’t usually nest near people, but to the city’s great pride and joy, they did start having chicks in Mandurah. It was a success story—until it wasn’t.

“Over the course of a few weeks, the cat managed to almost singlehandedly drive off the entire nesting colony of 220 birds, according to a study from Greenwell and her colleagues in the journal Animals. The cat was directly or indirectly responsible for the death of six adults and 40 chicks. Once it became clear the sanctuary was no longer safe, the entire colony abandoned the site. The nesting sanctuary was ultimately a failure.”

Photo: The blue hour

Poem: Karl Kirchwey, “Gold Fibula”

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments