Breaking up Facebook, Gatsby in Oxford, and the Revolution in Keeping Time

I enjoyed meeting a few Prufrock readers at TAC’s annual gala last night, which was a big success. Keep an eye out for videos of the interview with J. D. Vance and talks, which I’m sure will be available soon.

Meanwhile, back to business. The big news item yesterday was Chris Hughes’s piece in The New York Times calling for Facebook to be broken up. It ain’t the most elegant cut of prose, and I don’t think Hughes is the right person to make this argument. Still, he may be right about this: “We are a nation with a tradition of reining in monopolies, no matter how well intentioned the leaders of these companies may be. Mark’s power is unprecedented and un-American.”

Felix Simon and Lucas Graves discuss the use of paywalls by news organizations in America and Europe. They are becoming more common, but they aren’t as common as you might think: “Paywalls may seem to be everywhere these days, but how widespread are they in fact? This is the question Lucas Graves and I tried to address when we set out to survey the current pay model landscape across six European countries (Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom) and the U.S. When we first conducted a similar study in 2017, pay models had already spread across nearly two-thirds of newspaper sites in Europe. Two years have passed since then — eons in the rapidly evolving news environment — which is why we thought that it was time for a much-needed update. So what did we find?”

Gatsby in Oxford: “While F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is probably the most studied novel in modern American literature, Christopher A. Snyder’s Gatsby’s Oxford considers the book from an important, if somewhat overlooked angle: its hero’s declaration that he was ‘an Oxford man.’ Through this lens, Snyder — a professor at Mississippi State University and a research fellow at Oxford — examines the English university’s place in Fitzgerald’s imagination and, particularly, its associations with Romantic poetry, medieval traditions and architectural beauty.”

Exploring Doggerland: “Lost at the bottom of the North Sea almost eight millennia ago, a vast land area between England and southern Scandinavia which was home to thousands of stone age settlers is about to be rediscovered. Marine experts, scientists and archaeologists have spent the past 15 years meticulously mapping thousands of kilometres under water in the hope of unearthing lost tribes of prehistoric Britain.”

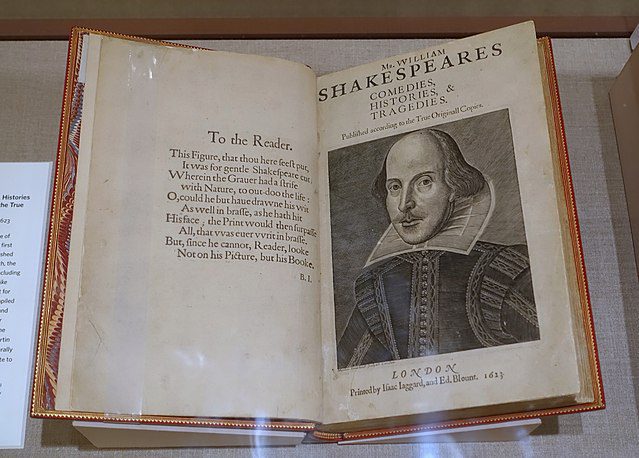

The unfinished story of a First Folio: “In October 1976, a book collector paid £2,400 (approximately £18,300 today) for a book in ‘damaged home-made burlap binding, which was in tatters’. The paper was ‘spongy’. Certain leaves were missing, certain leaves frayed, and certain leaves scrawled on. Could this be the same book that I have just seen – ahead of its appearance at ‘Firsts’: London’s Rare Book Fair next month – and heard valued, informally but informedly, at something like a couple of million pounds? Yes but, in some sense, no . . .”

Essay of the Day:

In Aeon, Paul J Kosmin writes about the revolution of keeping “universal and linear” time:

“What year is it? It’s 2019, obviously. An easy question. Last year was 2018. Next year will be 2020. We are confident that a century ago it was 1919, and in 1,000 years it will be 3019, if there is anyone left to name it. All of us are fluent with these years; we, and most of the world, use them without thinking. They are ubiquitous. As a child I used to line up my pennies by year of minting, and now I carefully note dates of publication in my scholarly articles.

“Now, imagine inhabiting a world without such a numbered timeline for ordering current events, memories and future hopes. For from earliest recorded history right up to the years after Alexander the Great’s conquests in the late 4th century BCE, historical time – the public and annual marking of the passage of years – could be measured only in three ways: by unique events, by annual offices, or by royal lifecycles.

“In ancient Mesopotamia, years could be designated by an outstanding event of the preceding 12 months: something could be said to happen, for instance, in the year when king Naram-Sin reached the sources of the Tigris and Euphrates river, or when king Enlil-bani made for the god Ninurta three very large copper statues. Alternatively, events could be dated by giving the name of the holder of an annual office of state: something happened in the year when two named Romans were consuls, or when an elite Athenian was chief magistrate, and so on. Finally, and most commonly in the kingdoms of antiquity, events could be dated by counting the throne year of the monarch: the fifth year of Alexander the Great, the 40th year of king Nebuchadnezzar II, and so on.

“Each of these systems was geographically localised. There was no transcendent or translocal system for locating oneself in the flow of history. How could one synchronise events at geographical distance, or between states? Take the example of the Peloponnesian War, fought between Athens and Sparta in the last third of the 5th century BCE. This is how the great Athenian historian Thucydides attempted to date its outbreak: ‘The ‘Thirty Years’ Peace’, which was entered into after the conquest of Euboea, lasted 14 years; in the 15th year, in the 48th year of the priesthood of Chrysis at Argos, and when Aenesias was magistrate at Sparta, and there still being two months left of the magistracy of Pythodorus at Athens, six months after the battle of Potidaea, and at the beginning of spring, a Theban force a little over 300 strong … at about the first watch of the night made an armed entry into Plataea, a Boeotian town in alliance with Athens.’

“Where we would write, simply, ‘431 BCE’, Thucydides was obliged to synchronise the first shot of war to non-overlapping diplomatic, religious, civic, military, seasonal and hourly data points. The dates are intimately tied to central state institutions, dependent on bureaucratic list-making, applicable only within a self-limiting geography, and highly sensitive to political change. Indeed, they are not really dates at all, so much as synchronisms between multiple events, coordinating a network of better and lesser-known occurrences: what is being dated, and what dates it, belong to the same order of things. Imagine giving the date of the invasion of Iraq, your grandma’s birth or American independence in such a manner; and then try to explain this to someone from another country.”

Photo: Črni Kal Viaduct

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments