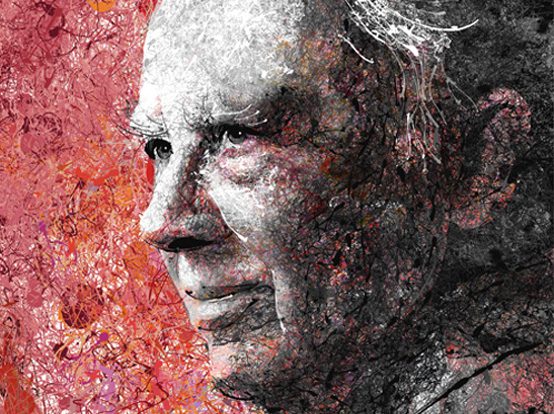

Russell Kirk and the Logos

To find the truth in history, the grand Russell Kirk argued in the late 1960s, one must approach the subject with all due humility, respect, and prudence. One must never “indulge in dreamy visions of unborn ages, or to predict the inevitability of some political domination.”

As Kirk rightly understood, no one has the right to impose his own ego, unnecessarily, on the past, the present, or the future. As all formal history is written by persons, the person must, of course, see the world (past, present, or future) through his own eyes. This is a given. But, that means that the historian has an even greater duty to his subject and to the republic of letters to diminish the personal ego as much as possible.

The real historian, as with the true poet, understands that one must recognize that the Logos is the center of all thought, all history, all grace, all goodness, and all purpose. “A reformed history must be imaginative and humane; like poetry, like the great novel, it must be personal rather than abstract, ethical rather than ideological,” Kirk claimed. “Like the poet, the historian must understand that devotion to truth is not identical with the cult of facts.” A search for history, then, is a search for the Logos. “Rather, the truths of history, the real meanings, are to be discovered in what history can teach us about the framework of the Logos,” Kirk wrote, “about the significance of human existence: about the splendor and the misery of our condition.”

The irony of this is that the best faculty for understanding the Logos is not through the very human passions or the intellect, but, rather, through the aristocratic soul, the mirror of the Divine. As St. John had written in the 9th verse of the first chapter of his gospel, the Logos (the Word) is “that which lighteth every man’s soul.” Man understands the world best, as such, through the Image provided to him by the Divine through his soul. “Images are representations of mysteries, necessarily,” Kirk observed, “for mere words are tools that break in the hand, and it has not pleased God that man should be saved by logic, abstract reason, alone.” If one takes the Image properly, as intended by the Image maker, it will “raise us on high, as did Dante’s high dream.” If soiled by the prideful ego, though, “it can draw us down to the abyss.” The Image offered by the Divine allows us not to create that which can and should never be, but to discover that which has always been there, but either forgotten, ignored, or mocked. “It is imagery, rather than some narrowly deductive and inductive process, which gives us great poetry and scientific insights,” Kirk stated in a 1977 public address, and “it is true of great philosophy, before Plato and since him, that the enduring philosopher sees things in images initially.”

In his own arguments, Kirk drew upon centuries and centuries of tradition. One of the Inklings—the group centered around J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis in the 1930s and 1940s—had written perceptively in his Oxford undergraduate thesis:

“Our sophistication, like Odin’s, has cost us an eye; and now it is the language of poets, in so far as they create true metaphors, which must restore this unity conceptually, after it has been lost from perception. Thus, the ‘before-unapprehended’ relationship of which Shelley spoke, are in a sense ‘forgotten’ relationships. For though they were never yet apprehended, they were at one time seen. And imagination can see them again.” Tolkien himself, named after St. John and having taken St. John as his patron saint, wrote to his former student, W.H. Auden, each person is “an allegory . . . each embodying in a particular tale and clothed in the garments of time and place, universal truth and everlasting life.”

For Tolkien and Kirk (as well as Owen Barfield, quoted above), the Logos provided the eternal and incorruptible essence of divine and human existence, while the mythos (story and history) gave the individual and personal manifestations of the Logos a context, rooted in a specific space and time. Writers, public intellectuals, professors, scholars, and men of letters, Kirk argued, must especially embrace the public duty of serving the Word.

“This unity and this spirited defiance of the vulgar came, in considerable part, from the Schoolmen’s [Thomist Scholastics] convictions that they were Guardians of the Word, fulfilling a sacred function, and so secure in the right” in their medieval universities. Americans, too, have inherited this sacred duty. “The principle support to academic freedom, in the classical world, the medieval world, and the American educational tradition, has been the conviction, among scholars and teachers, that they are Bearers of the Word—dedicated men, whose first obligation is to Truth, and that a Truth derived from apprehension of an order more than natural or material.”

Not surprisingly, Kirk’s patron saint, St. Augustine, had understood all of this as well. Drawing equally upon Virgil and St. John, the last and greatest of the classical thinkers had written in a homily on the Psalms:

Of itself it hath no light, nor of itself powers; but all that is fair in a soul is virtue and wisdom; but it neither is wise for itself, nor strong for itself, nor is itself light to itself, nor is itself virtue to itself. There is a certain fountain and origin of virtue, there is a certain root of wisdom, there is a certain, so to speak, if this also is to be said, region of immutable truth; from which if the soul withdraws it is made dark and if it draws near it is made light.

Saints John and Paul had, of course, also embraced—and, indeed, sanctified—the meaning of the Logos in their own Christian writings. While St. John had adopted it as the definition of the Divine Wisdom as found in the person of Jesus Christ in his gospel, St. Paul engaged the concept in a multitude of ways.

While the concept of the Logos might be older than the pre-Socratics, it was the pre-Socratic Heraclitus who had first named the Logos as the beginning of all things, the stuff of primary matter. At the heart of all things, Heraclitus thought, stood the artistic fire, the Word, the imagination, the spirit of the Logos. Not only did it exist at the beginning of all time and creation, but it would also serve, at some point, to bring all things back to itself.

Saint John and Paul, of course, identified Heraclitus’s Logos as and with Jesus Christ.

- 1 Corinthians 1:24 “but to those whom God had called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God.”

- II Cor. 4:4 “The god of this age has blinded the minds of unbelievers, so that they cannot see the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God.”

- 1 Colossians 15-20 “Who is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature: For in him were all things created in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones, or dominations, or principalities, or powers: all things were created by him and in him. And he is before all, and by him all things consist. And he is the head of the body, the church, who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he may hold the primacy: Because in him, it hath well pleased the Father, that all fullness should dwell; And through him to reconcile all things unto himself, making peace through the blood of his cross, both as to the things that are on earth, and the things that are in heaven.”

It was in his debates with the Stoics and Epicureans in Athens that St. Paul most blatantly referenced the Logos. As recorded in the seventeenth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles by St. Luke, St. Paul praised the Athenians for having, in humility and wisdom, recognized the “unknown god” through a statue. As it happened, Paul assured his audience, he had the identity of the unknown God, with these words: “In Him we move and live and have our being.” St. Paul took this line from the “Cretica” by Epimenides, a Greek of the sixth or seventh century, B.C.:

Minos to his father, Zeus

They fashioned a tomb for thee, O holy and high one—

The Cretans, always liars, evil beasts, idle bellies! (Titus 1:12)

But thou art not dead: thou livest and abidest forever,

For in thee we live and move and have our being (Acts 17:28).

Again, in Hebrews 1:3, one finds the following: “The Son is the radiance of God’s glory and the exact representation of his being, sustaining all things by his powerful word.” Though no authorship has ever been given to Hebrews, the author clearly understood the Logos as passed down from the Greeks as well as through the Hellenistic Jews. In the Jewish Book of Wisdom, written, most likely, sometime around 100BC, the eighteenth chapter predicts the coming of the Incarnate Logos.

For while gentle silence enveloped all things, and night in its swift course was now half gone, thy all-powerful word leaped from heaven, from the royal throne, into the midst of the land that was doomed, a stern warrior carrying the sharp sword of thy authentic command, and stood and filled all things with death, and touched heaven while standing on the earth.

Even one of the greatest of pagans, the Roman poet Virgil, had predicted something similar around 50BC:

The last great age the Sybil told has come;

The new order of centuries is born;

The Virgin now returns, and the reign of Saturn;

The new generation now comes down from heaven. . . .

Our crimes are going to be erased at last.

This child will share in the life of the gods and he

Will see and be seen in the company of heroes,

And he will be the ruler of a world

Made peaceful by the merits of his father.

Admittedly, our culture is far beyond a quick return to the traditional understanding of the Logos. On this, the 100th anniversary of Russell Kirk’s birth, it is well to remember that his conservative vision, his vision for conserving history, was not some bizarre and abstract wish. It was rooted deeply and profoundly in the western tradition, reaching back to before the pre-Socratics, through Heraclitus (ca. 510BC) and his naming of the Logos as the primary matters of the universe, through Zeno and the Stoics, through Virgil and Cicero, through Saints John, Paul, and Augustine, through St. Thomas More and Edmund Burke, and through Owen Barfield, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, T.S. Eliot.

In the 1950s, Kirk expressed exactly why the Logos meant to much, especially in decadent times. It is fitting to give him the last word: “In an age of decadence, the Stoic philosophy [of the Logos] held together the civil social order of imperial Rome, and taught thinking men the nature of true freedom, which is not dependent upon swords and laws.”

Worth conserving in any era.

Bradley J. Birzer is The American Conservative’s scholar-at-large. He also holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College and is the author, most recently, of Russell Kirk: American Conservative.

Comments