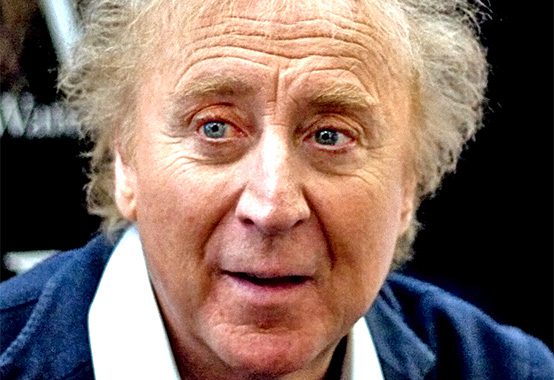

The Last of the Sensitive New Age Jewish Guys

Gene Wilder was something special.

I don’t just mean his extraordinary comic talent. He had that, of course, but the pool of talent is always being refreshed and renewed. And I don’t even mean that he was such a mensch — which he was as well. Believe it or not, there are nice guys born every minute, and not all of them are suckers.

But Wilder had a very distinctive persona, one that I valued enormously, and which I fear has passed from the scene for good.

Wilder was part of a wave of Jewish screen actors in the late 1960s and 1970s who made “Jewish leading man” a thing. Of course there had been plenty of Jewish leading men in Hollywood before this, from Kirk Douglas to Paul Newman to Tony Curtis. But they didn’t “play” their Jewishness as part of their persona. And there were Jewish leading men who did “play” their Jewishness — you can go back to Groucho Marx for examples.

But Gene Wilder, along with guys like Woody Allen, Dustin Hoffman, Elliott Gould and others of their generation, did something new by being as unambiguously Jewish as they were, with all the quirks and foibles that came along with that, while simultaneously being leading men. Not sneaking or insinuating or conning their way into the position: just being there. Their moves were recognizably Jewish, but they were legitimate moves. You could see why they would work.

Wilder, though, had different moves than most of the others. While Hoffman and Allen and the rest were working the “smart is sexy” angle, Wilder’s thing was: sensitive is sexy.

Think about the sequence at the bar early in “Stir Crazy.” In his conversation with Richard Pryor, it’s clear that he’s slept with multiple women at the bar; he’s a “player.” But there’s not only nothing braggadocious about the way he talks about the women he’s known; he reminisces specifically about their qualities of soul. This ingenuousness, and this interest in the hearts of people he only knows casually, clearly has a great deal to do with how he’s gotten to know them intimately so easily. It’s what gets him into danger, both at the bar and, later, in prison. But it’s also the way he gets himself out of danger. He leads something of a charmed life, because he’s fundamentally innocent, but an innocent possessed of the usual human share of lust and fear.

“Innocence” is not a quality I associate with his knowing compatriots. But it’s what made Wilder’s victories in his films so compelling. He wasn’t a yearning, striving, hungry Duddy Kravitz type. He didn’t expect the world to hurt him — he was surprised when it wanted to hurt him, over and over again. And then he was delighted when it didn’t.

That innocence, and that sensitivity, is a quality Wilder brought to virtually all his roles, from Leo Bloom in “The Producers” to Avram in “The Frisco Kid.” And with it came a profound sadness, because the world just isn’t as sensitive as he is, a sadness manifest from “Willy Wonka” to “Blazing Saddles” to his performances as the Fox in “The Little Prince” and as the Mock Turtle in a television version of “Alice in Wonderland.” But it was a sadness, not a whiny hurt. Wilder wasn’t a man child looking for a mother to soothe him, of the kind we have plenty of these days. He was a man, with a man’s desires and a man’s knowledge of the world, but with a child’s heart.

It’s a rare quality in any person, at any time, and a precious one for that reason. In whom, among our leading men, does it live now?

Comments