At Least We Still Have Dick Nixon To Kick Around

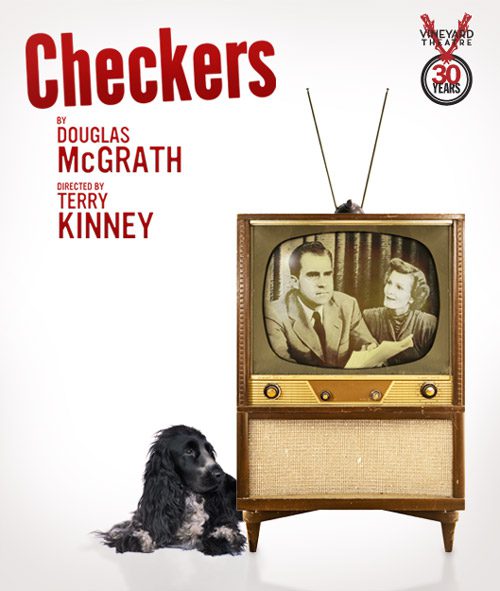

Or, at any rate, they still have him at The Vineyard Theatre. That’s where Checkers, a new play about Nixon by Douglas McGrath, directed by Terry Kinney and starring Anthony LaPaglia as the great man and Kathryn Erbe as Pat, is running through December 2nd.

The play is framed by scenes in 1966, as Nixon contemplates running for President again, prompted by his old campaign manager, Murray Chotiner (played with delicious foulness by Lewis J. Stadlen). Nixon’s main worry isn’t beating Johnson (who he presumed he would face), but dealing with the GOP establishment. Thinking about this casts him back to 1952, and the crisis that nearly got him kicked off the Eisenhower ticket, which would have ended his career. The crisis that he singlehandedly solved by giving a speech about a dog. Checkers.

Most of the play takes place in that extended flashback to 1952, taking us from the moment Nixon joins the ticket as designated attack-dog, through the allegations about a secret fund and Nixon’s anxious waiting by the phone to hear from General Eisenhower what was to become of him, to the speech itself. And then we bounce back to 1966, as Nixon, steamrolling over his wife’s desperate objections, decides to go for the brass ring once again.

For a play about politics, it’s strikingly dramatic, and that’s because there’s so much palpable tension throughout the flashback section. We feel for Nixon in his time of trial, not only because the play sets us up to identify with him, but because the situation is so suspenseful. We forget we know the history, and are straining to learn – will Eisenhower ever call? When he calls, will he give Nixon some assurance that he’s still on the ticket? If he won’t, will Nixon pull it off with the most important speech of his career? If he does, will that mean he’s finally accepted? It’s great theater, and a testament to McGrath’s skills as a craftsman, to a remarkably warm and engaging performance as Nixon by LaPaglia, and to a simple but profound performance as Pat by Erbe, who really becomes the center of the play, not only morally but dramatically.

What’s most surprising about the play is how thoroughly it takes Nixon’s side. Yes, you see the man’s obvious flaws – even Pat does; she warns him that “resentment is not a good governing principle.” But she knows that he has a best self as well as a worst self, and we see that side of Nixon, too – in quiet moments with her, but also in his connections with ordinary voters, which seem entirely genuine. His populist enthusiasms are treated as similarly sincere; his explanations of the fund are never questioned by the play – but neither are his explanations for his crusade against Communists in the State Department. The presumption is that Nixon was an honorable man dedicated to public service – and plainer in his dealing with other human beings than the establishment Republicans who tried to knock him off.

It’s almost refreshing to hear Nixon applauded rather than excoriated for hounding Helen Gahagan Douglas, but I don’t get the sense McGrath made this choice for political reasons, but rather to simplify the storytelling. And that’s a problem, because I’m not entirely sure what this is a story about, in a thematic sense, if it isn’t about Nixon as a figure in American political history. And it can’t be about that without reckoning with the fascinatingly contradictory meaning of Nixon politically: red-baiter and architect of detente; right-wing populist and centrist moderate; apostle of the good Republican cloth coat and of the Imperial Presidency.

Is it about politics as such? Perhaps. That’s what Pat thinks – that politics isn’t a game for decent people, so decent people like the Nixons should stay out of it. Inasmuch as, at the end of the play, we wind up siding with Pat, wishing Nixon hadn’t betrayed his promise to her, and had retired to private life, we wind up implicitly taking the side of the Brahmins who never wanted Nixon in politics anyway. We wind up concluding: yeah, guys like you – decent, ordinary Americans of talent but without the culture and connections of the hereditary elite – shouldn’t go into politics, because politics will ruin your character. But that idea, if taken seriously as a political principle, pretty much rules out government of the people, by the people and for the people.

Nixon is still with us because his constituency, and his style of politics, is still with us. And they are still with us because the right still doesn’t have an answer for how to involve that constituency actively in politics (which is necessary for the protection of their interests) without resorting to a Nixonian politics of resentment – which, indeed, does not make for a good governing principle. That’s why his story is a big one. By leaving those questions out of the frame, and focusing on the man in the arena – and the lions circling him for the kill – McGrath makes a big story smaller than it needs to be.

But even at an unnecessarily diminished scale, it’s a riveting story.

Comments