Nostalgia And 9-11-2021

I thought about not writing about today’s anniversary. Not because it hurts — it doesn’t, not anymore — but because it seems to be the thing I never could have imagined on that day twenty years ago that this thing could ever be: banal.

Which seems obscene, given, you know. But I think the banalization of 9/11 must be a part of healing from its trauma. If we stayed in that moment, in the place we all were on this day two decades ago, we would never have been able to get on with life. I think of the living room of my sister’s house in the country. Ten years ago next week, she collapsed on the floor there and drowned in her own blood as her helpless husband tried to save her. It was useless; the tumor had finally cut through her aorta, and it was the end. On a warm September morning. She was 42, and left behind three children. Now that living room is just where the kids, now grown, watch TV when they come home to visit their father.

It’s horrible, but it’s necessary. After that day, my wife and I swore that we would never, ever forget. Even if the rest of the country moved on, we would keep faith with New York, we would keep faith with all the men from our neighborhood fire station who perished that day. We would keep faith with America. But here we are, like everybody else. This is life. When I reflect on where those feelings of solidarity, of anger, and of the burning desire for vengeance took me, I am not sorry to see it all in the past.

Over the years, I would sometimes meet new people, and if 9/11 would come up in conversation, and they would find out that I had been there that day, in New York, they would look shocked, and ask me to tell the story. The telling of the story became a kind of liturgy, one that I grew to detest because with each telling, another layer was added to the scar tissue. The telling of the story did not keep it alive, but rather the opposite: it helped to kill its emotional power, at least within me. I know that by the time I hear the line one day, Tell us, Granddad, about what it was like to be there on 9/11, I might as well be reading out of a history book written by somebody else. I can’t explain that.

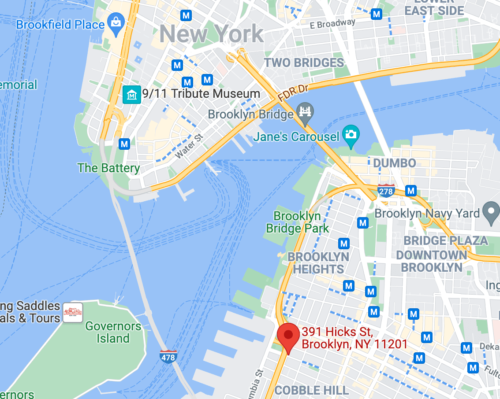

Here, in brief, is what happened to me, and where it happened. On that morning, my wife, toddler son, and I lived at 391 Hicks Street in Brooklyn — just across the harbor from the Twin Towers, which were the first thing we saw in the morning when we opened our front door:

My father in Louisiana called that morning to say, “Look out your front door, the Twin Towers are on fire!” He was watching the Today Show at home, and knew before I did what was going on in my own city. I did as he said, and saw a shower of papers falling over us gathered on the street. The wind was carrying the plume of smoke from the burning north tower directly over us in Brooklyn, carrying papers from the tower’s offices on the current.

I was a columnist at the New York Post, and had been planning to go in at noon because I was going to write something about local elections scheduled for that day, and knew it would be a late night. But surely now I would be writing something about the fire. I went down into our basement living room and began to gather my things to head across the river to cover it. As I sat in my office chair next to the desktop computer pulling my sneakers on, I heard screaming from the street above, then an explosion that shook our building. My wife opened the front door to see what was the matter, and then yelled down to me, “They say a 747 hit the other tower!”

My first emotion was anger at the crowd. Of course it wasn’t a 747; that’s ridiculous. What is wrong with people? But when I reached the front door to see for myself, and saw the south tower engulfed in smoke, I knew they had been correct. With my pen and notebook in hand, I kissed my wife goodbye in the doorway, and said, “This is terrorism. I’m going to get as close as I can.”

I set out for the Brooklyn Bridge, headed into lower Manhattan. I stopped to interview people in the shell-shocked line of victims staggering away from the calamity. Some were bleeding from the glass. I delayed my progress inadvertently by halting to interview them. By the time I got to the pillars on the far side of the bridge, I ran into a Post colleague who was out riding her bike; she was not scheduled to show up for duty until the afternoon.

“I need to get down there,” I said to her, trying to excuse myself after a can you believe it? exchange.

“Don’t do it,” she warned. “Those things are going to fall.”

I looked at her like she had lost her mind. “They’re not going to fall,” I said. “That’s the Twin Towers we’re talking about.”

Forty-five seconds later, there was a horrible roar, a Niagara of glass, and down came the south tower. I felt electric pincers clamp my knees, and they buckled. A woman to my right leaned over the bridge railing and vomited. A stout young black woman in front of me threw her hands into the air, and shouted a verse from the Bible, “‘And every knee shall bow, and every tongue confess!'” she howled. “It ain’t over, people!”

I had the presence of mind to know that if I was going to get into lower Manhattan, I had better run for it, because the police were going to close the bridge at any moment. Everything in me said go for it. I knew there would never be a bigger story in all my life, and there I was, at the white-hot center. I thought of the adventure. I thought of the glory. The dust cloud roared down the canyons of lower Manhattan, and obscured the foot of the bridge. I just had a few seconds to get there by running towards the cloud. But I thought then about my young wife and baby boy back home in Brooklyn, and how if I died that day, she would be widowed and he would be fatherless. I was instantly overcome with a sense of shame at my selfishness. But I really wanted to run toward the disaster, not out of a sense of courage (I’m sorry to admit), but because I’ve always been the sort of person who wants to be right in the middle of the action. It’s why I became a journalist. For me, courage had nothing to do with it; it was sheer curiosity, and the overwhelming urge to write about what I saw.

Unlike the firefighters of New York, I had a choice that morning of what to do. I did not have time to think about this forever. The dust cloud enveloped us. I turned around and walked back to Brooklyn, reckoning that Julie and Matthew were more important than my adventure and my glory.

Later, when it became clear that I would not have died had I been on the scene, but not inside the towers, I regretted what I had done. But in that moment of decision on the bridge, I discovered who I was. I discovered that my wife and child mattered more to me than I did. Take that for what it’s worth.

When I got back home, I was well-dusted. My wife met me at the front door holding our son, and sobbing. She had not been able to reach me by mobile phone, because the system was down. For about an hour, she thought I was dead. I went into the house, washed up, then down to the basement to file a column. Later, I went to the next block to Long Island College Hospital to join the long line of people waiting to give blood for the victims. They turned us all away, in the end. It turned out that there were no wounded. You either lived, or you died.

That afternoon, I walked around my neighborhood to get a feel of the street. On Atlantic Avenue, there were at the time a number of Arab-owned businesses. Near the corner of Atlantic and Court Street, I passed an old Arab man in Middle Eastern dress, looking towards what we would come to call Ground Zero, muttering, “Allahu akbar” — God is great. I wanted to slug him, because I thought he was praising the terrorists’ deed. I had only heard that phrase in connection with bad Arabs celebrating slaughter. Later, I would learn that “Allahu akbar” is also the Arabic version of “Lord, have mercy,” or “Oh my God.” Thinking back on it, that moment of misunderstanding on the streetcorner was the first mistake of that kind I would make in this saga, though not the last.

It was a terrible autumn, but one that disclosed beauty the likes of which I will surely never see again. All the people in our neighborhood going to the fire station in Brooklyn Heights to give money for the families of the dead firemen, and to bring food for those left behind. Standing on the streets sobbing as a fireman funeral cortege passed by. Going to Ground Zero to stare into the mouth of hell, through a fence festooned with missing flyers, from families who were hoping that somebody had seen their loved one. The thing I remember is the intense kindness with which New Yorkers treated each other. It was as if in the light of the 9/11 apocalypse, we discovered who we really were — or at least who we could be, if we wanted to be.

It didn’t last. It couldn’t last. For me, all the intensity of that autumn and winter concentrated itself in an overwhelming desire for revenge. I don’t need to recap that story here. I’ve said many times in this space over the years how my passions overwhelmed my reason, and left me vulnerable to the manipulation of government leaders who wanted to make war on Iraq. I thought that only we who had been there at the center of the apocalypse understood what it was really about. Those people who were against the war were either fools, cowards, or innocently ignorant of the stakes. We knew. We had seen the towers fall with our own eyes. We had been christened with the dusty remains of human beings. We had been to the funerals. We knew.

We didn’t know.

The thing that is hard to convey to people who weren’t alive then, or who were only children, is how emotionally and psychologically overwhelming this all was at the time. When I’m feeling charitable towards George W. Bush and the government leadership, I recall that they didn’t stand aloof from all this either. They were caught up in the same dynamic as the rest of us. The way I felt as a New Yorker, about how privileged my knowledge and judgment was because I had seen 9/11 up close — they surely felt far more that way, as government leaders privy to all the intelligence. Once, years into the war, I spoke to a White House official who had left his job, about all that. He said to me that it was hell going to work every day, knowing what the intelligence agencies were telling the president about threats they were picking up. Can’t you imagine it?

There’s no need to rehash the sorry story of what our government did, marching us to the forever war. I would just point out that it required a strong sense of judgment at the time to say no to the war. Pat Buchanan and the other founders of this magazine had it. So did others. But man, I tell you, the feeling in the country at the time was so pro-war. We had all been through 9/11, one way or the other, and we had all sat through Colin Powell’s presentation about Iraq at the UN, and the administration’s messaging about how the next 9/11 would involve a mushroom cloud if we didn’t wage war on Iraq.

Madness, all of it. I was taken in by it. So were most Americans. On this anniversary, I salute all of those, of whatever political conviction, who were not.

For me, I can’t separate 9/11 from the Catholic Church scandal. In a Rome speech delivered on this day three years ago, about the Benedict Option, Monsignor George Gänswein, the personal secretary to Benedict XVI, called the abuse scandal “the 9/11 of the Catholic Church.” I can’t forget that the Geoghan trial took place in January 2002, not four months from 9/11. That was what kicked off the scandal. By late summer, I was so consumed with rage and grief over both 9/11 and the abuse scandal that my wife begged me to see a therapist.

By 2005, I was gutted by the evil in the Church that I had learned of, and by the lies upon lies told by the bishops to cover their asses. That was the year that I learned from a good friend of mine who had been high up in the Pentagon about how Donald Rumsfeld had repeatedly and consciously lied about the war to the American people. That had shattered my friend, a military man who was a straight-laced Republican, but who never was again after that. And that was the year of Katrina, which revealed our government’s incompetence.

When I look back at it, 9/11 (and the Geoghan trial shortly after) was when the planes hit my personal towers, but 2005 was when they collapsed. I ceased to be able to believe in the Republican Party and in my government. I ceased to be able to believe in the Catholic Church. I fell into a deep depression, a crisis of confidence, and and I have never really come out of it. Then, in 2008, came the economic crash, and I stopped being able to believe in the competence and goodness of the people who run this country.

Still, you have to get on with life. “Stagger onward rejoicing,” said Auden. One does what one can, with a limp from war wounds.

Earlier this week in Italy, a Catholic friend of mine was telling me that all of us believing Christians have to figure out some way to live in the reality I describe in The Benedict Option and Live Not By Lies, without the reliable guidance of our leaders, especially our religious leaders. He’s right. I’ve believed that for a long time.

Twenty years ago, I thought that America would respond to the challenge of 9/11 with renewed patriotism and purpose, setting evildoers to rights and showing the world our righteousness. I really did believe that. I believed a lot of things back then. The past twenty years for me have been one of loss after loss, with one illusion after the other falling. As I mentioned above, next week marks the tenth anniversary of my sister’s passing. I moved with my wife and children from Philadelphia to my small Southern hometown with the hope and intention of renewing the family bonds. In fact, I learned that as far as the prodigal son was concerned, the image of a happy, harmonious family was a story everybody told themselves about who we were. That all dissolved too.

What’s left? I think about that a lot. Even when I try not to think about that, I think about that. I live in the shadow of the past twenty years. For the past year, I have been obsessed with the 1983 Andrei Tarkovsky Italian language film Nostalghia. In an interview about the movie, the Russian filmmaker, who died in 1986, explained that the word “nostalgia” means something different to Russians than it does to people in the West:

Nostalgia is a feeling of intense sadness over the period that went missing at a time when we forsook counting on our internal gifts, to properly arrange and utilize them … and thus neglected to do our duty.

I am nostalgic about 9/11 in that sense. I am sure that people older than me had Vietnam nostalgia in the same sense. America learned nothing from Vietnam. America will probably learn nothing from 9/11. Still: May the souls of the faithful departed — those who perished on this day, and those who perished in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere because of this day — rest in peace.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.