The Very Big Deal Catholic Crisis

I have been in Italy one week, and have had countless rich, stimulating conversations with Italian Catholic friends. Yet I find that I struggle to convey the gravity of the scandal roiling the US Catholic Church. It doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to many folks here. Some think it’s nothing more than a political attack on Pope Francis. Others agree that it’s bad, but they say the Church has always been corrupt to a certain degree, and don’t grasp why Americans are so worked up about it.

“The thing you have to understand about Italians,” said a journalist friend today, “is that we think the Church has always been there, and always will be. And we think that the Pope is usually right, whoever he is. It’s our natural stance.”

(Mind you, he wasn’t justifying it, only explaining to me why there is so much resistance here to the idea that this current scandal is a Very Big Deal.)

Well, I wish I could print out Jonathan V. Last’s new piece in the Weekly Standard and hand out copies to every Italian Catholic I meet who is interested in talking about the scandal — and even those who aren’t (because it truly is a Very Big Deal). This is the best piece I’ve yet read summarizing the situation and delineating its stakes. It is a lucid review of what we know about the scandal, and what it means. Let’s dive in, shall we?

Last sums up the McCarrick situation thus:

If true, this would mean that we have one cardinal who was a sanctioned sexual predator, (at least) one cardinal who turned a blind eye to this man’s crimes as they were happening within his jurisdiction, and a pope who didn’t just look the other way but took affirmative steps to help both the criminal and his enabler.

And if all of that is true, well, then what? The potential answers to this question aren’t very nice. They include: schism, the destruction of the papacy, and a long war for the soul of the Catholic church. Because the story of Theodore McCarrick isn’t just a story about sexual abuse. It’s about institutions and power.

Yes, exactly. It is about sex, and it is about money, but at bottom it’s about power, and its abuse. More:

The institutional damage is done not by the abusers but by the structures that cover for them, excuse them, and advance them. Viewed in that way, the damage done to the Catholic church by Cardinal Wuerl—and every other bishop who knew about McCarrick and stayed silent—is several orders of magnitude greater than that done by McCarrick himself.

By way of analogy, consider the dirty cop. About once a week we see evidence of police officers behaving in ways that range from the imprudent to the illegal. It has no doubt been this way since Hammurabi deputized the first lawman. But while individuals might be harmed by rogue cops, the system of law enforcement isn’t jeopardized by police misbehavior. The damage to the system comes when the other mechanisms of law enforcement protect, rather than prosecute, bad cops. If that happens often enough, citizens can eventually decide that the system is broken and take to the ballot box to reform it. The laity have no such recourse with the church.

This point cannot be emphasized strongly enough! People have been saying to me for a dozen years now, “Why did you leave the Catholic Church over pedophile priests? Every church is going to have pedophiles. That doesn’t make the teachings of the Church untrue.”

Yes, I know.

It wasn’t the pedophile priests that did in my faith. It was the bishops who protected them. That is, the men who ran the system were so morally and spiritually corrupt that in most cases they went out of their way to protect pedophile priests at the expense of children and their families. A priest friend back in 2002 told me that it was impossible to understand the sexual abuse scandal apart from a more general crisis in the Catholic Church. For example (he said), bishops protected these pedophile priests in part because they had lost a sense that the Church is supposed to be about something greater than serving the perceived interests of its ruling class (the clergy). The failure to react like any normal human being would to a sin as horrific as child molestation was in part a manifestation of a loss of sense of sin, period. Bishops had come to see themselves primarily as managers of an institution — an institution whose chief goal was its own perpetuation.

I could go on like this on a number of topics. The point is, the Church crisis is, as the kids like to say these days, intersectional. At some juncture, I quit believing that the US bishops, on the whole, cared about anything but protecting themselves. Once I lost that faith, it became hard to hold on to the belief that my eternal salvation depended on maintaining communion with them. I have said before that leaving the Catholic Church was, for me, like being an animal with its leg caught in a trap, who chews off its own limb to escape. From what was I trying to escape? The certainty that there was nothing I or anyone else could do to change things. The bishops were willing to lie to everyone, including themselves, to preserve their power and status. If the Pope wasn’t willing to bring about justice and reform, then it wasn’t going to happen, period. Many of my friends had the inner strength to bear that. I did not. The weight of anger and depression broke me. People who fault me intellectually for losing my faith might as well blame a man with broken legs for dropping out of a marathon.

I don’t want to have those familiar theological arguments again in the comments of this thread. I’m simply trying to amplify the point that J.V. Last makes in his essay: that because the Catholic Church’s ecclesial structure, there is no way for people within it to hold bishops to account. It’s especially a Catholic thing, but not exclusively a Catholic thing. Four years ago, a reader of this blog named Steve Billingsley left this comment on a thread:

I served for a decade as a pastor in the United Methodist Church – whose U.S. membership has declined over 30% in the last 45 years despite a very real and vibrant plurality of theologically orthodox (small “o”) members (and a booming membership in Africa and Central and South America). I served in one of the saner and more healthy regions (Central Texas) and was continually frustrated by the persistent tendency to major on minors and a denominational bureaucracy that was self-indulgent and clueless. (When I left the UMC ministry – my district superintendent told me that he (along with over half of his colleagues) was on anti-depressants and that he suspected that when he retired he wouldn’t need them anymore.)

Understand – I’m not against anti-depressant medication – it can literally be a lifesaver for folks suffering from clinical depression – but he was telling me that his job environment was so toxic that he needed to drug himself to cope (and frankly saw no irony in that fact). This is just symbolic of the denial that so many in leadership in these denominations live in. Our annual conferences were multi-day exercises in self congratulation and furrowed brow deliberation over countless resolutions that accomplished nothing other than solidify the entrenched political power of the denominational apparatchiks. Clueless old-school church politicians fighting over the remaining scraps of organizational power deluding themselves into thinking all is well.

I wouldn’t characterize it as a “liberal” vs “conservative” divide or even simply as orthodoxy vs heresy. It is taking the faith seriously enough to wrestle with serious issues in one’s own life and the life of one’s church and to trust that the faith that was delivered to us by our forebears through centuries of struggles, victories and defeats is not to be lightly cast aside for passing trends and the spirit of the age.

This is pretty close to what I observed among the Catholic bishops. It wasn’t so much that they were evil (though some, like McCarrick, were) as that they just didn’t take things seriously. Maintaining organizational power — now that was something they took very seriously.

I wish to point out yet again historian Barbara Tuchman’s three aspects of why the Renaissance popes lost half of Europe to the Protestant Reformation:

1. obliviousness to the growing disaffection of constituents

2. primacy of self-aggrandizement

3. illusion of invulnerable status

Tuchman said that these are persistent aspects of folly, and recur throughout human institutions. It seems to me, though, that those in religious authority are especially vulnerable to them, because they convince themselves that they are working for God, and so everything they do must be correct because of the fact that they do it.

Back to Last. He writes about the deep confusion with which Francis has governed in his pontificate, and how radical Francis has been, and the long-term consequences of this pope’s actions, for which he refuses to be held accountable in any way (e.g., refusing to acknowledge the dubia, which are the Church’s mechanism for allowing cardinals to compel a pope to clarify things theologically). Last argues that Francis is laying the groundwork for a total renovation of Catholic teachings on marriage, family, and sexuality. And:

Whether or not it’s coincidence, the American bishops in the most jeopardy now—McCarrick, Wuerl, Cupich, Tobin—are also the ones closest to Francis and most supportive of his desire to revolutionize the church.

Last concludes with four options out of this crisis: papal resignation (extremely unlikely, and a bad idea); surrender (shrugging it all off, and thereby letting the wicked triumph); schism (a bad idea); and resistance.

By “resistance,” Last means the laity withholding funds from bishops, and organizing for the long game — like, laying the groundwork for future papacies. That seems to me to be the only reasonable path forward for Catholics, but as Last puts it in this piece, that is a political option (politics being the method by which power is organized and distributed).

The deepest and most necessary form of resistance, though, has to be in the daily lives of the faithful. I conceived The Benedict Option as a project of Christian resistance to post-Christian modernity. It would be necessary for Catholics even if a vigorous Benedict XVI were still on the papal throne. It is necessary for us non-Catholics too. The core problem facing all Christians in the West these days is not primarily political, though politics (in the sense that I indicated in the previous paragraph) are part of it.

But as Archbishop Georg Gänswein, the longtime personal secretary to Benedict XVI, said this week in the Vatican, the gravity of the crisis engulfing the Catholic Church today gives the Benedict Option a certain urgence.

Read the whole thing. I’m not kidding — please, read it. Every word.

I was in a taxi coming back to the hotel from lunch in Milan when an American Catholic friend texted me a link to Last’s piece. I read it in the car, then we continued texting about it. I told my friend that it deeply concerned me that so many Italians — including, of course, within the Vatican — simply do not grasp the seriousness of the moment, and the threat it poses to the stability of the Catholic Church. Many seem to be more afraid of moralism than the self-destruction Wuerl, McCarrick, and Francis are wreaking on the Church. He added:

And of course Ivereigh, Faggioli and others are trying to spin this as an American thing and to quarantine the contagion. We’ll see what happens. It looks like an irresistible force colliding with an immovable object. But when you expand the field of vision from the abuse crisis, narrowly speaking, to the bigger picture as Last has done, its hard to think the irresistible force can ultimately be resisted. There’s something world-historic going on here. And it’s going to be very, very rough.

Yes, it will be. Remember: Father Cassian of the monastery of Norcia said three years ago that Christians who want to make it through the darkness coming upon us with their faith intact had better do the Benedict Option. He couldn’t have foreseen this particular crisis, but now that it’s here, his words have incredible potency.

Finally, I want to share with you a powerful short piece from The Federalist, written by two Protestants who are worried about the Catholic crisis, and who explain why every Christian should be. Excerpt:

It is absolutely essential that Catholics grasp the depth of this crisis. As we have said, we think it will become as severe and as comprehensive as the crisis of the Protestant Reformation 500 years ago. With remarkable swiftness, Catholicism simply collapsed in what had been Catholic strongholds — most of Germany, Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Switzerland, England, Scotland, and very nearly France. In recent decades, Catholicism has likewise lost its grip in what had been bastions — like French Canada, Spain, Ireland, and Brazil.

Forty years ago, virtually the entire population of southern Ireland turned out to welcome Pope John Paul II. A few weeks ago, the Irish population essentially shunned the visiting Pope Francis, and the Irish prime minister gave him a stern lecture on his church’s reduced place in that country. What would St. Patrick, who, despite just escaping from slavery in pagan Ireland, returned to the island after hearing the screams of the damned in his dreams, think of the church today?

As goes Ireland, so will go the rest of Roman Catholic Christendom. The church in Germany has been rocked by scandal and there are thousands of known-victims. Already, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church is under judgment in Chile, the United States, Australia, France, and Honduras. The crisis has long since gone global.

In fact, as the Catholic scholar Benjamin Wiker has argued, the current crisis is more threatening for the Catholic Church than the Protestant Reformation 500 years ago. For one thing, the Reformation began in a society that was still overwhelmingly Christian. Some historians of the pre-Reformation period even argue that Christian piety was deepening and broadening in the run-up to the Reformation, and that the Christian laity was already assuming a more prominent role in managing church affairs (a development greatly accelerated by Lutherans and Calvinists). But the contemporary Western world seems rapidly to be losing whatever residual Christianity was left in it. That makes a Catholic recovery more problematic.

As the authors, Willis L. Krumholz and Robert Delahunty, point out, it simply will not do for Catholics to assume that because the Church has been through something like this before, and survived, that it will do so again. The Church in the West has never faced a crisis like this, precisely because it is happening in a post-Christian culture, and in a media environment in which news travels globally in an instant. Pope Francis’s strategic silence in response to the Viganò testimony might have worked in every previous century, but not this one. Technology, and the change in consciousness that it effects, will not let him get away with it.

And because this scandal is about power, the Church’s leadership cannot forget that the crisis occurs in an age of radical individualism, which is to say, radical democracy. As a cultural and psychological matter, people do not feel bound to remain under the authority of a hierarchy they deem corrupt or in any way unacceptable. Maybe they’re wrong to think that way, but that is what it means to live in modernity. The Catholic philosopher Charles Taylor says that we live in “a secular age” not because everyone has left religion behind, but because unlike prior to the Reformation, everyone knows that religion is at some level a choice. Everybody knows people who are not believers, and who seem to be doing okay. There are far, far fewer external boundaries — in law and culture — to keep individuals bound to particular religions, or religious institutions. This is the world we live in.

If you had looked out at, say, the Netherlands in 1955, you would have seen what looked on the surface to be a coherent, vibrant, popular church. And you would have been massively shocked when just a few years later, everything collapsed. Same with Ireland in more recent times. If you think America is an exception to this trend, you are not only wrong, but dangerously wrong.

Archbishop Gänswein used plainly apocalyptic language in his talk in Rome this week. This is a man who, serving Joseph Ratzinger as secretary since 2003, has been at the very summit of the Catholic Church. Now he’s talking soberly about this crisis as being perhaps part of the last and worst trial before the Second Coming.

Think about what that means. Think about the significance of a man who has seen what Georg Gänswein has seen, saying that.

The storm surge has just begun for Catholics. Prepare.

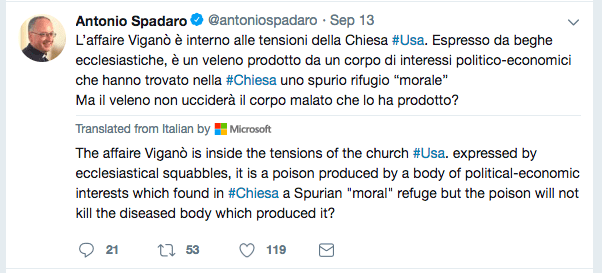

UPDATE: An Italian friend shared with me Father Antonio Spadaro’s tweet, which I’ve reproduced with the translation. You want to know one reason why Pope Francis is badly mishandling the scandal? This genius is one of his top advisors:

UPDATE.2: An Italian-speaking reader writes with a more accurate translation of Spadaro’s tweeet:

The Vigano affair is an internal matter related to the tensions within the Church in the United States. Created by ecclesiastical squabblers, it is a poison produced by a body of political-economic interests who have found in the Church a bogus “moral” refuge. Will we not soon see that the poison kills the diseased body which produced it?

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.