To Know Is to Love Is to Know

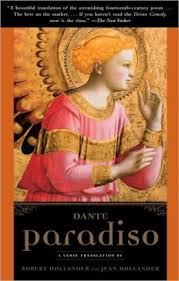

I am happy to report that at 12:45 am this morning, I read the final verses of the Divine Comedy. It was exhilarating, and it was nearly overwhelming. It took me  much longer to read Paradiso than Inferno and Purgatorio, because the language and the concepts are much denser and more abstract. This only makes the climb slower and more difficult. It’s also tremendously rewarding. I am going to be thinking about this for a long, long time, though I already know what I’m going to say in my forthcoming essay. I have never read a more audacious work of the imagination. When T.S. Eliot said that the two giants of Western literature are Shakespeare and Dante, and no other, I thought he might be overstating the case. I no longer believe that. You may never read the Divine Comedy, but if you’re thinking about it, know that it’s not only as good as they say, but that it’s more wondrous than you have imagined. But do make sure that you’ve found a translation you can live with, and one with great notes. I really love the Hollander translation, but I found the exhaustive notes to be, well, exhausting. I read Paradiso with the Ciardi at my side for his clear and excellent notes. This gets really unwieldy. If I had it to do again, I would probably buy the Mark Musa translation, which has the clarity, directness, and elegance of the Hollander, with Ciardi-like notes for non-specialists.

much longer to read Paradiso than Inferno and Purgatorio, because the language and the concepts are much denser and more abstract. This only makes the climb slower and more difficult. It’s also tremendously rewarding. I am going to be thinking about this for a long, long time, though I already know what I’m going to say in my forthcoming essay. I have never read a more audacious work of the imagination. When T.S. Eliot said that the two giants of Western literature are Shakespeare and Dante, and no other, I thought he might be overstating the case. I no longer believe that. You may never read the Divine Comedy, but if you’re thinking about it, know that it’s not only as good as they say, but that it’s more wondrous than you have imagined. But do make sure that you’ve found a translation you can live with, and one with great notes. I really love the Hollander translation, but I found the exhaustive notes to be, well, exhausting. I read Paradiso with the Ciardi at my side for his clear and excellent notes. This gets really unwieldy. If I had it to do again, I would probably buy the Mark Musa translation, which has the clarity, directness, and elegance of the Hollander, with Ciardi-like notes for non-specialists.

Anyway, one of the Big Ideas that stays with me from Paradiso is one that’s absolutely central to Eastern Christian theology, but also there in Western Christian theology: that the final end of all souls is theosis, or total unity with God. This is what Dante’s pilgrimage through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven is all about. Because the Christian God is a personal deity, to become united with Him is to know him in every sense. Because his essence is Love, you cannot ultimately know Him without also loving Him. Truth and goodness are separate but inseparable in God. Beatrice tells Dante, in Paradiso XXVII, speaking of the Seraphim and the Cherubim, which are the orders of angels existing in closest proximity to God:

‘And you should know that all of them delight

in measure of the depth to which their sight

can penetrate the truth, where every intellect finds rest.

‘From this, it may be seen, beatitude itself

is based upon the act of seeing,

not on that of love, which follows after,

‘and the measure of their sight reveals their worth,

which grace and proper will beget in them.

In Dante’s view (following St. Bonaventure’s), the Seraphim represent Love, and the Cherubim stand for Contemplation (that is, Knowledge). The poet says here (in Beatrice’s voice) that Knowledge — that is, seeing — precedes Love, because you have to first see something before you can love it, but that one is not higher than the other. They both work together. To know God is to love Him, and to love him is to know Him. Dante underscores the symbiotic relationship between knowledge and love by having St. Thomas Aquinas (a Dominican) speak in praise of the rival Franciscans, and St. Bonaventure (a Franciscans) speak in praise of the rival Dominicans.

Furthermore, for Dante, the deeper you see into the truth of things, the greater your love. This is what happens to him as he rises through the heavens, drawing closer to God. The journey is a series of unmaskings, with his sight improving the stronger in spirit Dante becomes. To prepare himself to look upon the final vision of Heaven — Heaven as it really is — Dante must baptize his eyes in a river of light. This is his final act to make himself ready to look upon the face of God.

In his book Universe Of Stone, about the building of the Chartres cathedral, Philip Ball talks about the neoplatonic “near-worship of light” that dominated the mind of 12th and 13th-century Europeans. Ball contends that this attitude towards light led to the architectural revolution of Gothic cathedrals, which flooded dark church interiors with light — light that was also analogized by the Schoolmen to Reason. Think of the Gospel of St. John, describing Christ, the Logos, as the “light that shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.”

Further, Ball writes:

This suggests that the mundane and material can lead us towards the transcendental and immaterial by an affinity of their essence is an example of the concept of anagogy (literally, “upward-leading”). It is a difficult idea for us who lack the Neo-Platonist’s sense of the connectedness of the universe or the medieval notion of world as symbol.

What he’s saying is that for the medievals, contemplation of ordinary things like stone and light can lead one to awareness of higher realities. The Divine Comedy is saturated with this kind of thinking. Indeed, Dante repeatedly indicates that the divine must communicate to us finite creatures symbolically, because we lack the vision to see divine reality as it truly is. As I said, the entire Paradiso is about a journey into sight, and into Dante’s growing in spiritual strength until he is at last capable of bearing heaven’s blinding light at full strength.

Interestingly, in Inferno and Purgatorio, Dante grows by acquiring knowledge of how sin works, and how man is corrupted, but he is also required to repent. In Paradiso, no one repents — it would be pointless to repent in Heaven — but Dante does grow in the power of vision as he learns more about divine reality by gazing up on the progressively higher levels of heavenly being, and by accustoming himself to the progressive experience of ever more intense light. The closer a creature is to God, the brighter it glows with the Uncreated Light, which indicates the degree to which it has been deified. Crucially, this is also in heaven a bond of love. The light of knowledge is different from but also inseparable from love.

It’s intense and heavy stuff, at least to a novice like me. It raises interesting philosophical question about the nature of ultimate truth. Or rather, it puts (for me) a somewhat new way of thinking about a familiar question: is truth objective or subjective? As you know, I think there are truths that are true whether or not you believe them. Mathematical and scientific truths are like this. But there is a category of truth that can only be realized subjectively. I believe, with Kierkegaard, that all the truths worth living and dying for are subjective truths, which is to say, things that are objectively true, but can only be properly realized in subjectivity. God is like this. God exists objectively, but that truth means nothing unless I appropriate it inwardly and commit myself as a subject to it. Here’s Kierkegaard’s own definition of truth (in this sense):

An objective uncertainty held fast in an appropriation-process of the most passionate inwardness is the truth, the highest truth attainable for the individual.

It would be wrong to call the The Divine Comedy pre-Kierkegaardian, but it’s not entirely crazy. What I mean is this: for Dante, growing in Truth is inseparable from growing in personal and intellectual union with God. It is not simply something one does with one’s mind, but with the totality of one’s being. The “intellect” is better understood by the Greek term “nous” (pron. noose) the perceiving faculty of the soul. For Orthodox Christians, salvation — which is to say, theosis, dissolving oneself in total unity with God — depends on sharpening one’s noetic vision. Though I hesitate to pronounce a Christian poet so thoroughly Scholasticized as Dante as one who is consonant with Orthodox theology — I ask your correction if I here err — it was remarkable to me, as an Orthodox Christian, to read Paradiso as a long poem about the cleansing of Dante’s nous (his ability to perceive God as He is), a cleansing that of necessity increased the divine love within Dante.

The thing is, he could not love to the utmost without having the strength and the clarity of vision to take in more light, and he could not take in more light without having the capacity to love more perfectly. Dante says that the act of seeing precedes the act of loving, and that makes rational sense. But isn’t it also true that some things cannot be perceived except insofar as one loves?

Here’s what I mean. You walk through the mall, you see strangers, but you don’t perceive the reality of those strangers. You can’t see them as they are, because you have no subjective experience of them. You don’t love them, and can’t love them, because you don’t know them. You perceive them in your eyesight, but you don’t see any deeper than the surface of these people, because you have no subjective knowledge of them. You don’t know them like their wives, their husbands, their children, their parents. You don’t, for that matter, know them like their Creator. Now, it is also true that within our subjectivity, we may fail to perceive objective truths about a person. The mother of the school bully may not perceive her child’s cruelty, for example. Only God, who has perfect omniscience — that is, perfect objective knowledge and perfect subjective knowledge — can say for sure. The point I want to make here, though, is that I don’t think Dante is quite right to say that perception always precedes love.

This is all speculation from an amateur, obviously. I hope that you who have been philosophically and theologically trained will help me better understand these concepts. It should be clear that I love this stuff, love this poem, love that Dante Alighieri.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.