TNC, Tolstoy, Dante

For a book I think is fairly awful, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me sure has occasioned a lot of reflection on my part. Christopher Caldwell called it a bad book on a worthy subject, and I agree with that assessment. One thing I admire about Coates is his urgent concern with justice, and reckoning with the injustices suffered by black people in this country. Read my much longer consideration of the book here. What I object to, primarily, is Coates’s extremely simplistic view of race, and racial justice, a view that seems to me to remove moral agency from blacks and to ascribe power to whites that many, probably most, do not have. Last summer, TNC spent his holiday at the elite French language camp at Middlebury. To do something like that would be for me a dream come true. For him, it was another opportunity to reflect on what he didn’t have growing up in the ghetto. As I wrote at the time, whites for him seem to exists in some sort of upper-middle-class fantasy world:

He’s right, of course, about what segregation and racism did in a systematic way to black Americans, but I think he’s off, and off in a way that matters, about what lower middle class white families can expect. Remember Tabi, the poor white girl from Pennsylvania that the Washington Post profiled? She was struggling mightily to break free from the poverty culture that was everywhere around her, and reinforced by her mother, her siblings, and just about everybody. Does TNC seriously think that Tabi would have it easier than he if she ended up at Middlebury for the summer?

Let’s say that Tabi isn’t lower middle class; she’s just poor, and therefore not an ideal example. I’ll consider my own case. My family was somewhere between lower middle and middle class. My dad worked as a health inspector; my mom drove a school bus. We lived in rural south Louisiana. I knew exactly one kid growing up who could be called rich, and he didn’t flaunt it. My folks expected my sister and me to make good grades, and we did, but all of this was disconnected from any broader intellectual culture. I don’t say that to fault them at all; my mom and dad were very good about buying me whatever books I wanted, and I’m grateful to them for it. The point I’m making is that in the family and local culture in which I was raised, the purpose of education was to be able to go to college and to get a good job. The end.

The idea that we, and people like us, could have expected “to live around a critical mass of people who are more affluent or worldly and thus see other things, be exposed to other practices and other cultures” is completely ridiculous, about two tics away from Eddie Murphy’s White Like Me clip. There were exactly two cultures visible to a child like me: the culture of white people, and the culture of black people. We shared a lot of things in common (like, well, school; there was one school, and we all attended it), but we were also quite different. In neither case did a child, black or white, see affluence and its culture. I suppose lower middle class looks affluent to someone who lives on welfare, but the point is, a white kid raised in West Feliciana in the 1970s and early 1980s had little or no intellectual culture of the sort that TNC imagines. The highest goal you aspired to was to attend LSU. Almost nobody thought of the Ivy League. When a friend of mine got into Brown, I was astonished that she had even thought to apply.

What does Tabi (“Her mother had five kids and no husband at age 23. Tabi, the last born, was a welfare and WIC baby who grew up with evictions and lights getting cut off”) owe to #1 New York Times best-selling author Ta-Nehisi Coates, because she’s white and he’s black?

The question itself points to the essential hopelessness of TNC’s project, which is to define and achieve justice for the extreme abuse and “plunder” (his word) that blacks have suffered throughout American history. The difficulty of determining a reliable dollar figure, plus the impossibility of pinning blame, means TNC’s project is doomed to end in failure and frustration. Besides, how can one ever compensate fairly for lives of suffering already concluded, even centuries ago?

The search for justice is central to Dante’s quest in the Commedia. It’s an extraordinarily complicated story (that is, the concept of Justice in the Commedia), but I have been thinking in light of TNC’s work of the nun Piccarda, in Paradiso, the third book of the Commedia. From How Dante Can Save Your Life:

The first blessed soul the pilgrim meets is Piccarda Donati, the sister of Forese Donati, the gaunt but joyful reformed glutton. In Florence, Piccarda was a nun kidnapped from her convent by her wicked brother Corso, who forced her to marry a man to seal a political alliance.

She is on the lowest level of paradise, a sphere reserved for those who failed to be entirely faithful to their vows. This doesn’t sit right with Dante. to his way of thinking, Piccarda did not abandon her vows of her own free will; she was forced. How can she be happy with God’s decision to assign her to heaven’s farthest reaches?

Piccarda answers him “with so much gladness she seemed alight with love’s first fire.” She says:

“Brother, the power of love subdues our will

so that we long for only what we have

. . . And in His will is our peace.”

Not only is love more important than justice, as Father Matthew once told me, but in heaven love is justice, and justice love. Accepting what you have been given with a grateful heart and not desiring anything else is the key to peace. According to the saintly Piccarda, it is not for us to question God’s plan.

Says Dante in response:

Then it was clear to me that everywhere in heaven is Paradise,

even if the grace of the highest Good

does not rain down in equal measure.

[Paradiso iii:88–90]

To be at peace is to cease to desire anything that God has not given. Heaven is a state of paradox in which everywhere is perfect, even though some places are at a higher degree of perfection than others. How can we speak of degrees of perfection? Because in heaven, we are perfected according to our own natures.

Piccarda, for example, bears as much divine light as her nature can accept. This reminded me of a teaching Father Matthew gave in a sermon one Sunday: “God doesn’t expect you to be St. Seraphim; he expects you to be the best version of the unique creation that is you.”

We learn from Piccarda that in the Kingdom of God, perfection is not perfect equality but perfect harmony. It I loved as I should love, I would love my family—indeed, love all people—and expect nothing in return. Inner peace depends on practicing gratitude for what I have, not complaining about what I lack.

Dante the poet uses the figure of Piccarda to illustrate how pure love doesn’t measure fairness and unfairness, doesn’t meditate on past wrongs, is not bound by envy or any earthly passion. Piccarda is free. Moreover, Piccarda is free in a way that I once was not. Now I can see that I was so knotted up by hurt over my family’s broken bonds that I could not let go of my passion for what I considered to be justice.

I could not remain that fourteen-year-old boy weeping in a field over his shame, his weakness, and the wounds delivered by the mockery of his father and his sister. I was a middle-aged man now. whatever their flaws, Daddy and Ruthie were not an excuse for me to shirk my responsibility to love. And it was easier to love them because I no longer served the false image I created of them. Rather, I served the God who made us all, and who expects us to love others as he loves us.

The hardest thing I had to overcome in my own struggle with the heavy legacy of my family was my desire for justice. It’s not that justice is wrong, but that it is not as important as love. This is a Christian teaching. As I spend these final days of my father’s life with him, I know that I would not have had the strength to be here serving him and loving him if it had not been for the power of God to push me and pull me off my obsession with justice — a justice that could never be realized in this life — and into the clear, rushing waters of love. It has been a hard three and a half years here, dealing with the crevasses in my family’s life, and with the dragons living therein. Yet when I think about how terrible it would have been had I not come here after my sister died, and if I were boarding a plane in Philadelphia now to come spend these final days and weeks with him, with so much unresolved between us, and now, given his condition, unresolvable — my God, it chills me to the bone. What a mercy it has been to me to have been able to let go of all that.

“When the Lord comes for you, Daddy, go in peace,” I said to him last night. “Know that you are loved, and that you have been loved. You have taken such good care of us.”

“I always tried to,” he murmured.

It really is true. The things that he did me wrong will never be made right. That life cannot be unlived. But then, the things that I did wrong to him — and there were some — cannot be undone either. Neither one of us are innocent. There are no innocents. But injustice can be overridden by love. I look at that suffering old man now, a man who once frightened me with his booming voice when angry, and now I see a man who can barely speak above a whisper. A man who used to heave massive blocks of firewood can today hardly raise his arms to let us change his shirt. Auden writes:

Into many a green valley

Drifts the appalling snow;

Time breaks the threaded dances

And the diver’s brilliant bow.

In the face of mortality — his, mine, ours — what is justice? What use is justice? As the Christian faith teaches us, we will be judged by the same standard we use for others. If we fail to love, even our enemies, we will be held accountable for that. I think of this excerpt from Dr. King’s 1957 Christmas sermon:

Do to us what you will and we will still love you. … Throw us in jail and we will still love you. Bomb our homes and threaten our children, and, as difficult as it is, we will still love you. Send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our communities at the midnight hour and drag us out on some wayside road and leave us half-dead as you beat us, and we will still love you. Send your propaganda agents around the country and make it appear that we are not fit, culturally and otherwise, for integration, but we’ll still love you. But be assured that we’ll wear you down by our capacity to suffer, and one way we will win our freedom. We will not only win freedom for ourselves; we will appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.

That is Christianity, pure and simple. TNC, who is an atheist, does not have access to this — yet, anyway.

This has been on my mind also these past few days because I’ve been reading short stories by Tolstoy to my two little ones at night. I don’t know Tolstoy’s work, so I’ve picked a couple of stories from what’s available online, according to their titles. As it turns out, both were about forgiveness. The one I read Saturday night to them was called “God Sees the Truth, But Waits.” It’s about a poor merchant who was framed for the murder of another man, and sent away to Siberia. Near the end of his life there, he finds himself in the presence of the real murderer, the one who framed him, and is offered the opportunity to see justice done. He chooses instead mercy.

On Sunday morning, the Gospel reading was the Parable of the Unmerciful Servant, which is about a servant who owed a greater debt than he could possibly pay, but who was forgiven it by his master. The servant, in turn, came down hard on a fellow servant who owed him little. When the master discovered how unmercifully the servant forgiven his debt had treated his fellow servant, he punished the unmerciful servant greatly. The lesson, of course, is that God forgives us our debt of sin that we could not possibly pay. What others owe to us is small compared to what we owe to God. So if we withhold forgiveness, and stand on justice, God will punish us.

That night, we read the Tolstoy story, “A Spark Neglected Burns the House,” and if you can believe it, that very story begins with the same Gospel text we had heard that morning! It’s a story about how a tiny sin, hardly a peccadillo, left unresolved grew into a moral conflagration that engulfed a community — a community that could only be brought back together through mutual forgiveness.

What is the lesson for us? That the only way forward for all of us Americans, black, white, and otherwise, is through love and forgiveness — and that goes both ways. When whites complain about what blacks exact from them, regarding welfare, or affirmative action, or even through the black crime rate, we run the very severe risk of being Unmerciful Servants, especially if we expect God to forgive us and our ancestors for the unspeakable crime and plunder of the black people of this country. The same goes for blacks, too. Scripture tells us that no man is righteous, not one.

To recap: justice in this life is impossible. Only God knows all hearts. Only God is fit to judge. All we can know is that as we judge, we shall be judged. Forgiveness is, at the very least, in our self-interest. And it is the only way to live at peace with oneself and the world. In His will is our peace. Not my peace alone, and not your peace, and not TNC’s peace — but our peace.

I don’t see any other way. One more lesson from How Dante Can Save Your Life:

When I think of envy, I imagine people wanting what others have. By that measure, my sister was not envious of me. But as I learned by reading the Commedia, that’s not the way medieval people thought of envy. To them, envy was resenting others for what they have. From what our parents told me about Ruthie, that was how she saw me. This is what it meant to be a “user” in my family’s parlance: someone who gets what he has at the expense of others. [Emphasis mine; this is the essence of TNC’s complaint regarding white “plunder” of black wealth. — RD]

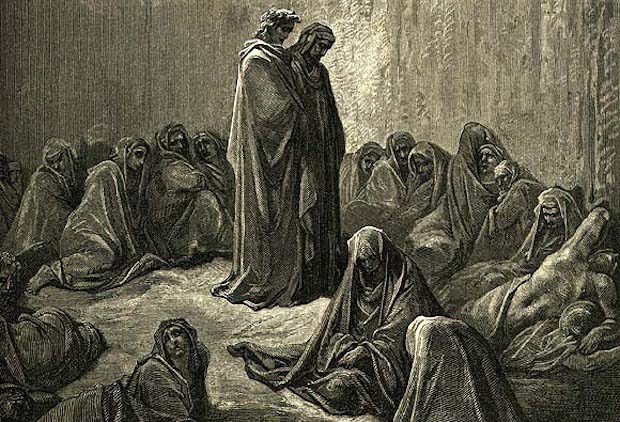

And Dante, confronting the penitent envious, sees a sight that renders his eyes “overwhelmed by grief.” There, huddled together against the side of the mountain out of fear of falling off the edge, sits a knot of shades, their eyes sewn shut with wire, “as is done to the untrained falcon because it won’t be calmed.”

In the mortal life, the envious cast their eyes with malice on others and wished them harm, or at least spited their good fortune. In so doing, they weakened the bonds of community. In purgatory, they are temporarily blinded and are forced to take hold of their neighbors, depending on them for safety and help in not falling off the mountain ledge. Tears of repentance seep from under the eyelids they cannot open.

The eyes of the envious are deprived of vision so they can learn to depend on their neighbor more and to “see” their neighbor with the inner eye of compassion and solidarity in shared suffering and shared protection from danger. When the wires come out of their eyelids, they will see with different eyes, with a vision that has been purified from the distorting lens of the self.

In the Commedia, Dante writes about the public consequences of the private sin of envy. The pilgrim meets penitents from Italy who lament the unraveling of the social fabric in their valley back home. The worldview of the people in that valley has become so corrupted by envy that either they cannot see virtue or they see virtue as vice. And their children and children’s children were suffering for it.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.