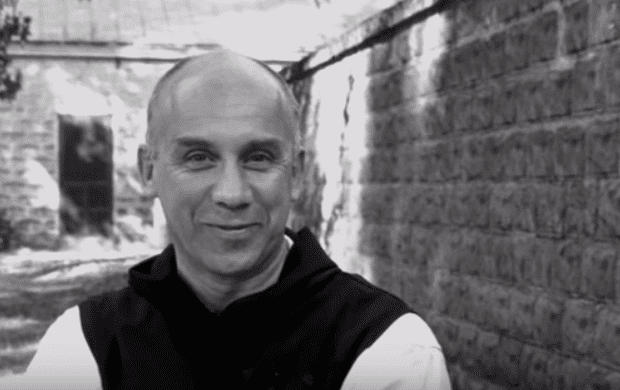

Thomas Merton: Pious Fraud?

Thomas Merton’s 1948 memoir The Seven Storey Mountain is, for me, the most important book I ever read. It had a lot to do with my conversion to Catholicism. Stumbling into the Chartres cathedral at 17 was the Road to Damascus moment; reading Merton a couple of years later was encountering a guide who took me by the hand and led me towards the city. It is one of the great American autobiographies, and revealed to me, a restless young religious seeker, how what I sought could be found in the Roman Catholic Church. I was a young man who had a lot in common with Merton. I had no idea at all that the Catholic Church that Merton entered had been discarded by most Catholics in my time. That would come later.

In the current Harpers, the progressive Catholic Garry Wills publishes a lacerating review of a new book about Merton, who comes across as a pious fraud. I’m not entirely surprised by any of this — Merton’s later writings, after he became famous, never interested me — but it is deeply disappointing to admit that on the basis of the information he provides in the essay, Wills is entirely correct. Merton hated being a Trappist monk, had no regard for spiritual and moral discipline, much less his brother monks. And worse! Here’s Wills:

Gregory Zilboorg, the first psychoanalyst who treated him, said, “You want a hermitage in Times Square with a large sign over it saying hermit.”

One year into life at his own hermitage, he found the place useful in an unanticipated way. In 1966, he had back surgery in a Louisville hospital, where he fell in love with a young student nurse. Though many people think he referred to her only as “M,” to protect her privacy, he wrote of her in his journal as Margie. (It was the editor of the relevant journal volume who first used “M.”) Merton had been visiting another psychiatrist, James Wygal, for his depression. The doctor, though he did not approve of the tryst, lent them (not for the last time) his office for their meeting. Later Merton wrote: “I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day at Wygal’s, and it haunts me.” In his poems to her, he would write of their “worshiping hands” and how “I cling to the round hull / Of your hips.” She was twenty-five; he was fifty-one.

He used trips to the airport for meeting literary friends as excuses for seeing her. She also met him in a woods by the abbey, bringing a picnic basket and a bottle of sauterne, where, he wrote, “[we] drank our wine and read poems and talked of ourselves and mostly made love and love and love.” When an overheard phone call to her was reported to his abbot, that official tried to break off the affair. Though the abbot did not want to lose Merton from Gethsemani, keeping him there while the affair continued would risk a scandal. Merton thought Abbot James Fox was inhuman and “jealous of me.” He was ordered by the abbot to make a complete break. The abbot asked for Margie’s name, to write her himself, explaining why there would be no more phone calls, but Merton refused.

More:

Merton’s commitment to Margie had always been hedged about with his prestige as a monk. “I don’t really want married life anyway; I want the life I have vowed.” Gordon is right to treat the six-month obsession with “M” as trivial in itself. This was never Shakespeare’s “marriage of true minds,” as exemplified by Abelard and Héloïse. Here deep did not call to deep, but shallow to shallow.

Oh man. Harsh! Read it all. It is painful to read of the contempt Merton had for his brother monks, and how they had become so financially dependent on him that they let him push them around.

I suppose you could cast this as Merton being a tortured soul, stretched as thin as a lute string between his spiritual aspirations and his robust carnality. Wills doesn’t extend that charity to Merton, and given that Merton called his brother monks at Gethsemani monastery “half-wits,” it’s not hard to understand and to share Wills’s parsimony.

I still strongly recommend The Seven Storey Mountain. It is a true classic written by a serious man seriously seeking God. It sounds like the book’s phenomenal success — it sold hundreds of thousands of copies when it was first published — may well have been the ruin of Merton.

UPDATE: Here’s a more balanced assessment from the Orthodox priest Patrick Henry Reardon, who, in his youth, was for a time a Trappist monk at Gethsemani, and knew Merton. In fact, he was one of two Trappists who stood at Merton’s bier reciting Psalms aloud, according to the custom. His fascinating essay appeared in Touchstone in 2011. For those who don’t know him, Father Pat is very far from a liberal, which puts his fond remembrances of Merton into a certain perspective. Excerpts:

Above all, Merton taught us to pray. Two particulars should be mentioned:

First, the Psalms: I had begun to pray the Psalms as a child, and in the monastery we recited—I counted them—284 Psalms each week. During the summer prior to joining the monastery, I had read Merton’s newly published Bread in the Wilderness, which introduced me to the Christological praying of the Psalter. He gave the novices copious tutelage on this theme, though I had no idea at the time that the Psalter would become a dominant preoccupation for the rest of my life.

Second, repetitive prayer: Merton also introduced us to the practice of “the Jesus Prayer,” the sustained repetition of the formula, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” (At the time, as I recall, he was reading articles on the Jesus Prayer in the Belgian journal, Irenikon.) I adopted this form of prayer with a steady application, and it is still one of the most important components of my relationship to God. Some years ago, Touchstone published an article of mine on this subject (“The Prayer of the Publican,” Fall 1996).

At the time I joined the novitiate, Merton’s interests seemed to lie chiefly in the Fathers of the Church and the literature of Christian mysticism. This was still the case, I believe, when I was tonsured in late spring of 1958 and moved over to the “professed side” with the other monks. This was the year Merton published Thoughts in Solitude, a work in which there was no sign, as yet, that things would soon change in a very big way.

Father Pat talks about the earthquake that was the Second Vatican Council, and how it affected the monks. More:

Although Merton’s interests developed extensively during the 1960s, his readers—and even friends—are far from agreed whether that development necessarily represented an improvement. Nor will I try to settle the matter here.

It is worth observing, nonetheless, that Merton interpreted that later process not as an evolution but as a repudiation of his earlier work. Even making allowance for hyperbole in his declarations on the matter, it is difficult to escape the impression that The Seven Storey Mountain genuinely embarrassed the later Merton.

Well, his books are all out there and available, so let everybody choose his favorite. For my part, I regard The Seven Storey Mountain as Merton’s absolutely best book and the one most likely to be read a century from now.

Father Pat goes on to say that his own spirituality and convictions are so far removed from Merton’s that he can’t be considered a “disciple” of Merton’s, even though some have called him that. But:

I am certain of this much: My memories of him are warmly cherished—his exuberance and sharp wit, the agility of his imagination, his compassion, his capacious intellect, his love of living things, his profound humility and personal resilience, his enthusiasm for study and prayer, and the sarcasm he occasionally doled out to the deserving. Sometimes even his faults—his impetuosity and frequent displays of annoyance—were endearing. Or at least entertaining!

Read it all. That Merton made such a positive and lasting impression on a man of such deep conservative theological conviction and integrity as Father Patrick Henry Reardon surely says something good about the man.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.