The Perils Of Evangelical Art Criticism

My Southern Baptist pal Joe Carter posted this comment on the above on Twitter this morning:

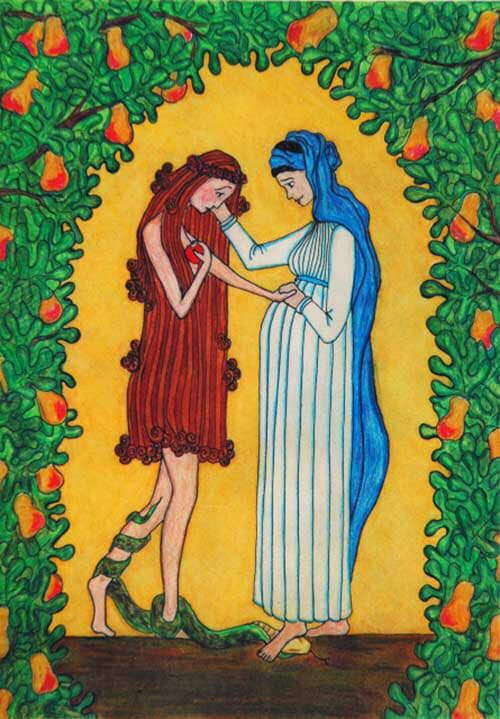

Now that it’s Advent I’ve begun my annual tradition of complaining/explaining to Protestants that no matter how charming you find this picture, it’s presenting heretical theology (i.e., Mary as co-redemptrix). pic.twitter.com/TKJFxeiGSz

— Joe Carter (@joecarter) December 3, 2018

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Well, he’s wrong about that. For the record, neither Catholics nor Orthodox see Mary as “co-redemptrix.” But that’s not actually what this image says, anyway. I explained it to Joe, and he replied:

I’d have no objection to interpreting the image that way if the straightforward meaning (Mary crushes the serpent) wasn’t an entrenched heresy. Because it is, I just think it’s better to avoid confusion than hope all viewers read into it an orthodox meaning.

— Joe Carter (@joecarter) December 3, 2018

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

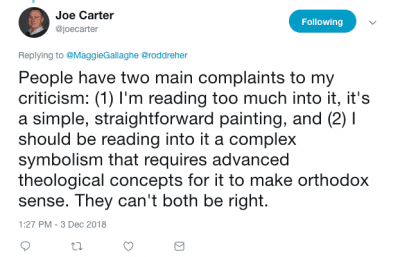

He goes on to say:

Yes they can. My argument is that the image is easy to interpret. Eve’s disobedience to God allowed the Serpent to triumph, entangling humankind in the curse of original sin — that is to say, the Fall. Mary’s obedience to God — “Let it be done to me according to Thy word” — set into motion Redemption. That is, the reversal of the Fall. Symbolically speaking, the image is meant to comfort Eve by telling her that her Redeemer is coming. The Serpent that she allowed to conquer her (and through her, humankind) has been crushed by Jesus Christ, who empowers those who believe in Him to overcome the Serpent’s guile.

It is common to see images of Mary crushing the Serpent’s head — this, as an answer to Genesis 3:15, in which God’s curse on humankind says that the Serpent will bite at the heel of Adam and Eve’s offspring. The idea is that Mary is a New Eve, through whom God restores Creation. In traditional Christian thought, Mary’s “yes” to God reverses Eve’s “no” to Him in the Garden. Eve’s “no” — symbolizing Man’s rebellion — set into motion a chain of events that brought death upon the world. Mary’s “yes” opened the door to the Incarnation, the birth of the Redeemer, who would later die on the Cross, and resurrect on the third day.

The image shows the role that all of us play in the drama of fall and redemption. God did not force Eve to disobey; she did of her own free will. God did not force Mary to say yes to His bizarre request; she did of her own free will. Similarly, God does not compel any of us to commit sins; He has given us free will, and we do so by our own choice. Nor does He compel us to say yes to Him; we are free to do as we wish. By choosing life, we unite ourselves to the One who conquered death. There is a beautiful poetic symmetry in this image, which depicts how sin is conquered: by saying yes to God. Our own will plays a part in our redemption.

To be clear: there is no “co-redeemer” of any kind in Christianity. There is only one Redeemer, Jesus Christ. This image teaches us something about the economy of salvation: that God, Who could do anything, loves us so much that He gives us freedom to decide to accept or reject Him. His work of salvation is in vain for those who reject the free gift.

The reason this is an Advent image is that traditional Christians — including many Protestant churches — celebrate this liturgical season as the beginning of redemption. That’s what the Incarnation means.

In my view, Joe — who, again, is my pal; this is an argument among friends — is needlessly complicating the image. And his “better to avoid confusion” stance typifies what I find so off-putting about popular Evangelical approaches to art. Must everything really be reduced to the lowest common understanding? If you go into the 12th century Chartres cathedral, you will find it difficult to understand all the symbolism. But Christians of that era could do so. Indeed the symbolism in the windows and carvings at Chartres conveyed theological truths to people who could not read, but who could read the images. You wouldn’t build a cathedral today that had such complex Christian symbolism in it, because 21st century people have lost the ability to read it.

On the other hand, there’s a reason why traditional (not post-Vatican II) Catholic and Orthodox churches don’t look like Southern Baptist churches: because those forms of Christianity are strongly incarnational in their theology, and believe that Creation testifies to an ordered cosmos.

It is hard for someone today to walk into an Orthodox church off the street and be able to read all the symbolism in Orthodox icons at first glance. You have to learn the language. Orthodox cultures raise their children with that symbolic language. I asked my 14-year-old son to come look at the Advent image above, and to interpret it for me. This is not an image we use in the Orthodox church, so it was fresh to him. But he got it perfectly, because the symbolic language he has learned as an Orthodox Christian helped him to understand what the artist is conveying.

The standard complaint that non-Evangelical Christians have about Evangelical approaches to art is that Evangelicals too often refuse subtlety, irony, and indirection, out of fear that the purity of the message may be compromised. While I genuinely appreciate Joe’s taking the power of image seriously, I believe in this case he imputes a false interpretation to an image that beautifully renders a basic Christian truth about salvation, and endorses an approach to sacred art that would keep art on a primitive level.

I’m happy to see a discussion about this in the comments thread, but let me warn you: anybody who tries to deride or insult Christians on either side of the debate will not be published. Criticism is fine; mockery is not. I will also not publish atheist snarkery about whether or not Eve really existed. That’s not what this discussion is about.

UPDATE: I have learned from readers that even though the Roman church has not defined a dogma calling Mary “Co-Redemptrix,” there are some Catholics who believe that it ought to do so. It still seems a big stretch to me to interpret this image as presenting Mary as “Co-Redemptrix,” especially given that she is positioned as on the same level as Eve. But I do want to acknowledge that the Mary-as-Co-Redemptrix thing is more common among Catholics than I realized.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.