The End of Our Time

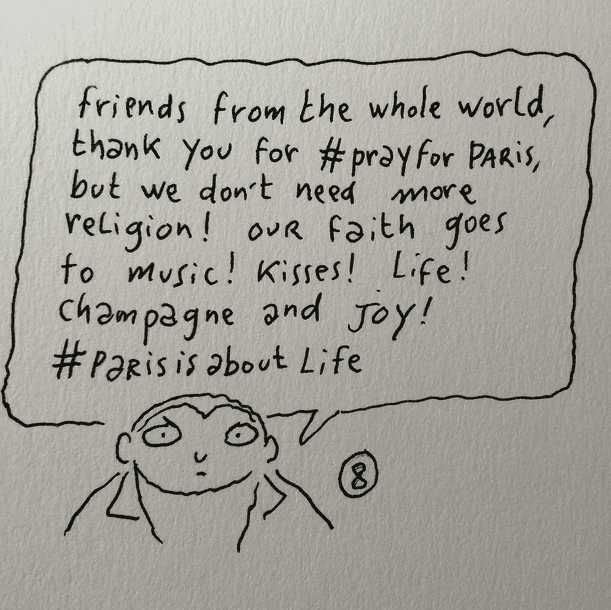

A reader sent that cartoon to me. It’s by Joann Sfar, a Charlie Hebdo cartoonist, and it’s a response to people around the world who are offering prayers for Paris. No sir, Parisians like the atheist Sfar have no desire for prayers. Religion, you see, is the problem. If only everyone would be a thoroughly secular person like Sfar, these difficulties would resolve themselves.

The other day, a musician with a peace sign painted on his piano set up outside the devastated Bataclan nightclub, and played John Lennon’s nihilistic ballad “Imagine”:

Imagine there’s no heaven

It’s easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us only sky

Imagine all the people

Living for today…Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

Imagine all the people

Living life in peace…You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will be as one

I credit the sweetness of the anonymous musician’s spirit, but the more I thought about that gesture, the angrier I grew. Why angry? Because this — and the Sfar cartoon — are emblematic of the decadence and despair and emptiness of the post-Christian West. I keep saying, “You can’t fight something with nothing,” and that’s exactly what “Imagine,” and the Sfar cartoon stand for: nothing. Believe me, I celebrate music! kisses! life! Champagne and joy! too — it’s one of the reasons I love Paris madly — but it is not enough, and it will never be enough.

The simpering message of “Imagine,” the brittle secularist pride of Sfar’s cartoon — really? That’s all you have to offer?

The historian Niall Ferguson writes that the Paris attacks, and the ongoing swamping of Europe by migrants, is a clear warning. It’s behind a pay wall. Excerpts:

Here is how Edward Gibbon described the Goths’ sack of Rome in August 410AD: “ … In the hour of savage licence, when every passion was inflamed, and every restraint was removed … a cruel slaughter was made of the Romans; and … the streets of the city were filled with dead bodies … Whenever the Barbarians were provoked by opposition, they extended the promiscuous massacre to the feeble, the innocent, and the helpless …”

Now, does that not describe the scenes we witnessed in Paris on Friday night?

Ferguson quotes the Oxford historian Bryan Ward-Perkins, whom I once interviewed about this very topic:

Recently, however, a new generation of historians has raised the possibility the process of Roman decline was in fact sudden — and bloody — rather than smooth.

For Bryan Ward-Perkins, what happened was “violent seizure … by barbarian invaders”. The end of the Roman west, he writes in The Fall of Rome (2005), “witnessed horrors and dislocation of a kind I sincerely hope never to have to live through; and it destroyed a complex civilisation, throwing the inhabitants of the West back to a standard of living typical of prehistoric times”.

In five decades the population of Rome itself fell by three-quarters. Archaeological evidence from the late 5th century — inferior housing, more primitive pottery, fewer coins, smaller cattle — shows the benign influence of Rome diminished rapidly in the rest of western Europe.

“The end of civilisation”, in Ward-Perkins’s phrase, came within a single generation.

And:

“Romans before the fall,” wrote Ward-Perkins, “were as certain as we are today that their world would continue for ever substantially unchanged. They were wrong. We would be wise not to repeat their complacency.”

Poor, poor Paris. Killed by complacency.

It’s not just Paris, and this is very, very much not something that can be solved or prevented by force of arms. Yesterday I spent a long time on the phone with the Russian novelist Evgeny Vodolazkin, from his home in St. Petersburg. I wrote late last month about his stunning novel Laurus, a critical and commercial success in Russia, recently translated into English. I interviewed him for this blog, and will be publishing the entire text of our conversation later. We started, though, by talking about the events in Paris. Vodolazkin had been in Prague when news of the attacks reached him. He told me that just as World War I wasn’t really about an assassination in Sarajevo, so too is the West’s current crisis not truly about Islamists who shoot up concert halls.

He added that the West has never seen a migration like the current one, with so many masses of people moving from East to West, at once. He described it as “a great historical event.”

“Nobody knows how this experiment will end,” he said. “The best thing we can do now is to pray. To tell the truth, I don’t see any way out of this tunnel.”

I spent much of this past weekend reading Michel Houellebecq’s novel Submission. I can’t recall the last time I read a work of fiction that was so slight — it reads like Houellebecq wrote it in a week — yet seemed to be so profoundly diagnostic of its time. It’s not a great book, and not really a very good book, but it’s an important one, a novelistic canary in the coal mine, and I strongly urge you to read it. It’s about the despair of contemporary France, but there’s a lot in it that will resonate with Americans, and all over the West. Mark Lilla describes it well:

Michel Houellebecq has created a new genre—the dystopian conversion tale. Soumission [Its French title — RD] is not the story some expected of a coup d’état, and no one in it expresses hatred or even contempt of Muslims. It is about a man and a country who through indifference and exhaustion find themselves slouching toward Mecca. There is not even drama here—no clash of spiritual armies, no martyrdom, no final conflagration. Stuff just happens, as in all Houellebecq’s fiction. All one hears at the end is a bone-chilling sigh of collective relief. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come. Whatever.

The novel’s protagonist is François, an academic who teaches at the Sorbonne, and who is an expert on the 19th century novels of J-K Huysmans, who converted to Catholicism after a life of restless decadence. Lilla:

Houellebecq has said that originally the novel was to concern a man’s struggle, loosely based on Huysmans’s own, to embrace Catholicism after exhausting all the modern world had to offer. It was to be called La Conversion and Islam did not enter in. But he just could not make Catholicism work for him, and François’s experience in the abbey sounds like Houellebecq’s own as a writer, in a comic register. He only lasts two days there because he finds the sermons puerile, sex is taboo, and they won’t let him smoke. And so he heads off to the town of Rocamadour in southwest France, the impressive “citadel of faith” where medieval pilgrims once came to worship before the basilica’s statue of the Black Madonna. François is taken with the statue and keeps returning, not sure quite why, until:

I felt my individuality dissolve.… I was in a strange state. It seemed the Virgin was rising from her base and growing larger in the sky. The baby Jesus seemed ready to detach himself from her, and I felt that all he had to do was raise his right arm and the pagans and idolaters would be destroyed, and the keys of the world restored to him.

But when it is over he chalks the experience up to hypoglycemia and heads back to his hotel for confit de canard and a good night’s sleep. The next day he can’t repeat what happened. After a half hour of sitting he gets cold and heads back to his car to drive home.

It is the centerpiece of the novel, and the passage Houellebecq has said is its most important. Here, at a great medieval Catholic shrine, François will not let himself believe. I say “will not let himself,” but that is not clear. As he stands in front of the famous statue of the Black Madonna of Rocamadour, François stares at the child Jesus in her lap, and has a mystical moment of calling. He quotes a verse from the Catholic poet Charles Péguy:

Mother, behold your sons so lost to themselves.

Judge them not on a base intrigue

But welcome them back like the Prodigal Son.

Let them return to outstretched arms.

This is the moment of decision. François decides that he was having “an attack of mystical hypoglycemia.” And that is the end of that.

François makes one more attempt at Christianity. He visits a Benedictine monastery where Huysmans had become an oblate, but he’s irritable and immune to its spiritual appeal:

The voices of the monks rose up in the freezing air, pure, humble, well meaning. They were full of sweetness, hope, and expectation. The Lord Jesus would return, was about to return, and already the warmth of his presence filled their souls with joy. This was the one real theme of their chants, chants of sweet and organic expectation. That old queer Nietzsche had it right: Christianity was, at the end of the day, a feminine religion.

Later, in his room, François reads a pamphlet about spiritual direction for pilgrims:

“Life should be a continual loving exchange, in tribulations or in joy,” the good father wrote. “So make the most of these few days and exercise your capacity to love and be loved, in word and deed.” “Give it a rest, dipshit,” I’d snarl. “I’m alone in my room.”

What’s so interesting about François is that he’s fairly passionless. He’s middle-aged and all alone. He has sex (these passages are frankly pornographic), but there’s no emotion involved. He is incapable of forming attachments. He uses booze, cigarettes, good food, and porn (or pornographic sex) to distract himself from his misery and the pointlessness of his life. He longs for a past of faith, family, and domestication. Look at these passages:

When I got home I poured myself a big glass of wine and plunged back into En ménage. I remembered it as one of Huysmans’s best books, and from the first page, even after twenty years, I found my pleasure in reading it was miraculously intact. Never, perhaps, had the tepid happiness of an old couple been so lovingly described: “Andre and Jeanne soon felt nothing but blessed tenderness, maternal satisfaction, at sharing the same bed, at simply lying close together and talking before they turned back to tack and went to sleep.” It was beautiful, but was it realistic? Was it a viable prospect today? Clearly, it was connected with the pleasures of the table: “Gourmandise entered their lives as a new interest, brought on by their growing indifference to the flesh, like the passion of priests who, deprived of carnal joys, quiver before delicate viands and old wines.” Certainly, in an era when a wife bought and peeled the vegetables herself, trimmed the meat, and spent hours simmering the stew, a tender and nurturing relationship could take root; the evolution of comestible conditions had caused us to forget this feeling, which, in any case, as Huysmans frankly admits, is a weak substitute for the pleasures of the flesh.

François buys fancy French meals frozen, and microwaves them alone. Here’s another passage:

In the old days, people lived as families, that is to say, they reproduced, slogged through a few more years, long enough to see their children reach adulthood, then went to meet their Maker. The reasonable thing nowadays was for people to wait until they were closer to fifty or sixty and then move in together, when the one thing their aging, aching bodies craved was a familiar touch, reassuring and chaste, and when the delights of regional cuisine … took precedence over all other pleasures.

Houellebecq depicts a France where people do little more than shop, have sex, and talk about eating, drinking, real estate, and getting ahead in their careers. There is no purpose for individuals other than pleasing themselves, no animating vision for society. This, for Houellebecq, is why the West is dying: people have ceased to believe in their civilization, and do not want to make the sacrifices necessary to continue it — not if it is going to cost them the thing they value the most: individual liberty to choose one’s pleasures.

In the world of the novel — set in 2022 — French politics have failed, and a Muslim government comes to power as the result of a coalition of Socialists and mainstream conservative parties being determined to keep the National Front from being voted in. Mohammed Ben Abbes, the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood party, becomes president, and is an instant hit. He Islamifies the universities, and leads a general turn in French society towards modesty and conservatism. The Sorbonne is made an explicitly Muslim university, and one must convert to Islam to teach there. The non-Muslim faculty — including François — are discharged.

Rediger, a professor at the university known to François, accepts Islam, and is put in charge there. He tries to convince François to accept Islam, and rejoin the university. In a fascinating discussion, Rediger tells François that he had always known that religion was going to make a comeback in Europe, because no society can live without it. Earlier in his life, Rediger says, he was a Catholic nativist, but he grew to doubt that Europe would ever again be able to believe in Christianity.

“That Europe, which was the summit of human civilization, committed suicide in a matter of decades.” Rediger’s voice was sad. He’d left all the overhead lights off; the only illumination came from the lamp on his desk. “Throughout Europe there were anarchist and nihilist movements, calls for violence, the denial of moral law. And then a few years later it all came to an end with the unjustifiable madness of the First World War. Freud was not wrong, and neither was Thomas Mann: if France and Germany, the two most advanced, civilized nations in the world, could unleash this senseless slaughter, then Europe was dead….”

He converted to Islam, and found in it the secret to a successful life.

“It’s submission,” Rediger murmured. “The shocking and simple idea, which had never been so forcefully expressed, that the summit of human happiness resides in the most absolute submission.”

It must be said that fear that Submission is anti-Muslim is completely groundless. If anything, the Muslims in the novel are depicted as decent. My colleague Noah Millman, in his review of Submission, asked:

And the lingering question, in this reviewer’s mind at least, is: for whom, apart from Houellebecq himself, is this fantasy of submission especially appealing? If the book is a satire, who, precisely, is being satirized?

I read Submission differently from Noah. I agree with him that the fantasia of a Muslim government of France is wildly unlikely, nor do I think the French are on the verge of accepting submission to an Islamic order, however attenuated. But neither, it should be said, is the infamous novel The Camp of the Saints realistic. Like that earlier scandalous French work (which is turning out these days to be more realistic than one wishes it were), Submission creates a somewhat cartoonish world to shine a light on something real within French society. In an interview to which I link below, Houellebecq admits that it is unrealistic to imagine that a Muslim party would come together and win the presidency in such a short period of time, but it is not unthinkable decades from now. He says he is telescoping time for literary effect.

The protagonist of Submission is not remotely admirable, but he’s also such a nobody that he’s barely worth despising. He slouches through life, moved by nothing other than his appetites, and his intellectual interest in Huysmans. When he accepts Islam, it’s not because he believes in it. It’s because that is the way to achieve the things he wants most in life — a wife and children — without having to work at it. There is no grand moment of conversion; he just shrugs and accepts Islam (or rather, a facsimile thereof) as a solution to his problems.

But it’s a superficial solution. This pseudo-Islam of the French collaborators is not about Allah or the Prophet at all. The collaborators still drink alcohol, and they have a wife to cook for them and younger wives to service them sexually. It is a restoration of a previous patriarchal social order, one that, as conceived by President Ben Abbes, has explicitly political aims: to restore France, and Europe, to greatness. Islam is not a personal faith in Submission, but a religious ideology — something more vigorous than the dead, feminine Christianity — that undergirds the rebirth of the Roman Empire.

The key line in the novel is Rediger’s statement that “the summit of human happiness resides in the most absolute submission.” That is a truth that we post-Enlightenment Westerners cannot bear to hear. When the Self is the only thing to which we will submit, says the faithless Houellebecq, we cannot be other than atomized, lonely, without direction or purpose, and slaves to our own misery. Islam — the word means “submission,” and it refers to becoming the slave of Allah — takes away your freedom and returns to you purpose and a sense of transcendent meaning. Of course you can get that in Christianity too, and the true Christian thinks of himself as a servant of the Most High. Yet the Master that Christians serve is a very different one in character, and He will not force himself on us. Dostoevsky’s parable of The Grand Inquisitor teaches us that the Master of the Christian people grants them freedom. The Inquisitor, a Catholic cardinal, maintains that it is he and those like him who are the true benefactors of mankind, because they relieve suffering mankind of the burden of freedom.

In this way, Rediger is like the Grand Inquisitor: the new Islamic order to which he invites François is, ultimately, a release from the burden of freedom, a burden that François cannot handle — nor, implies Houellebecq, can contemporary France. The Muslim rulers, like the barbarians in Cavafy’s well-known poem about an exhausted wealthy people welcoming barbarian rule, “are a kind of solution.” People have to live for something beyond themselves, or they, both individually and as a people, will perish in aimless wandering. When France lived under submission to Christ the King — Houellebecq is thinking of the Middle Ages here — it achieved greatness of spirit, and produced things of lasting beauty. The puzzle that Submission leaves me with is why François (and, by extension, today’s French, and the Europeans) believe they cannot find this by returning to Christianity. I must think about this.

In this way, Rediger is like the Grand Inquisitor: the new Islamic order to which he invites François is, ultimately, a release from the burden of freedom, a burden that François cannot handle — nor, implies Houellebecq, can contemporary France. The Muslim rulers, like the barbarians in Cavafy’s well-known poem about an exhausted wealthy people welcoming barbarian rule, “are a kind of solution.” People have to live for something beyond themselves, or they, both individually and as a people, will perish in aimless wandering. When France lived under submission to Christ the King — Houellebecq is thinking of the Middle Ages here — it achieved greatness of spirit, and produced things of lasting beauty. The puzzle that Submission leaves me with is why François (and, by extension, today’s French, and the Europeans) believe they cannot find this by returning to Christianity. I must think about this.

In a good interview with Houellebecq in The Paris Review, the author says simply that a return to Catholicism is not a realistic prospect because it has “already run its course, it seems to belong to the past, it has defeated itself.” If this is true, though, why is it true? Houellebecq is not asked this question. He goes on:

“My book describes the destruction of the philosophy handed down by the Enlightenment, which no longer makes sense to anyone, or to very few people. Catholicism, by contrast, is doing rather well. I would maintain that an alliance between Catholics and Muslims is possible. We’ve seen it happen before, it could happen again.

You who have become an agnostic, you can look on cheerfully and watch the destruction of Enlightenment philosophy?

Yes. It has to happen sometime and it might as well be now. In this sense, too, I am a Comtean. We are in what he calls the metaphysical stage, which began in the Middle Ages and whose whole point was to destroy the phase that preceded it. In itself, it can produce nothing, just emptiness and unhappiness. So yes, I am hostile to Enlightenment philosophy, I need to make that perfectly clear.

This is because the Enlightenment has brought us to the dead-end life of shopping and screwing and the misery of individual sovereignty at which François has arrived. It is the Sfar cartoon, and “Imagine” outside the scene of a massacre. This is not to say that the Enlightenment was all bad, obviously, but only that it has taken us as far as it can, and is now a destructive force, a force that produces people who do not know how to submit to anything beyond their own disordered appetites, including rage.

Speaking of disordered rage, I finished Submission on the same day that I read Ross Douthat’s most recent column, which focuses on the roots turmoil on American campuses. I found a connection there. From Douthat’s piece:

Between the 19th century and the 1950s, the American university was gradually transformed from an institution intended to transmit knowledge into an institution designed to serve technocracy. The religious premises fell away, the classical curriculums were displaced by specialized majors, the humanities ceded pride of place to technical disciplines, and the professor’s role became more and more about research rather than instruction.

Over this period the university system became increasingly rich and powerful, a center of scientific progress and economic development. But it slowly lost the traditional sense of community, mission, and moral purpose. The ghost of an older humanism still haunted its libraries and classrooms, but students seeking wisdom and character could be forgiven for feeling like a distraction from the university’s real business.

Then, says Douthat, came the 1960s radicals, who sought to “remoralize” the university, though theirs was certainly not a return to traditional morality. Douthat says that university administrators managed to co-opt the Sixties radicalism, and use “left-wing pieties” in college discourse to mask a deeper spirit that was “technocratic, careerist and basically amoral.”

Now there’s a new, fierce radicalism back on campus, and Douthat does not agree with much of what they stand for. But he pays them a certain respect:

The protesters at Yale and Missouri and a longer list of schools stand accused of being spoiled, silly, self-dramatizing – and many of them are. But they’re also dealing with a university system that’s genuinely corrupt, and that’s long relied on rote appeals to the activists’ own left-wing pieties to cloak its utter lack of higher purpose.

And within this system, the contemporary college student is actually a strange blend of the pampered and the exploited.

This is true of the college football recruit who’s a god on campus but also an unpaid cog in a lucrative football franchise that has a public college vestigially attached.

It’s true of the liberal arts student who’s saddled with absurd debts to pay for an education that doesn’t even try to pass along any version of Matthew Arnold’s “best which has been thought and said,” and often just induces mental breakdowns in the pursuit of worldly success.

It’s true of the working class or minority student who’s expected to lend a patina of diversity to a campus organized to deliver good times to rich kids whose parents pay full freight. And then it’s true of the rich girl who discovers the same university that promised her a carefree Rumspringa (justified on high feminist principle, of course) doesn’t want to hear a word about what happened to her at that frat party over the weekend.

The protesters may be obnoxious enemies of free debate, in other words, but they aren’t wrong to smell the rot around them. And they’re vindicated every time they push and an administrator caves: It’s proof that they have a monopoly on moral spine, and that any small-l liberal alternative is simply hollow.

Read the whole thing. It’s one of the more important pieces you will read all year. Think of it when you look at something like this idiotic nonsense that happened yesterday at Clemson University:

Breaking the Bathroom Binary

Monday, November 16 at 10:00am to 2:00pm

Hendrix Student Center, Restrooms

720 McMillan Rd., Clemson, SC 29634, USA<Part of Trans* Week of Awareness, various restrooms across campus will be temporarily transformed into non-gendered restrooms. This experience will allow folks to experience a non-gendered, fully inclusive restroom and see what the difference is (or is not).

It costs $24,000 per year for in-state residents to attend Clemson, and almost twice that for out-of-state residents. Is Trans Week of Awareness emblematic of the Clemson experience? Almost certainly not. It is a surpassingly trivial event, but it nevertheless tells us something important about the indoctrination of the next generation. The Clemson alum who sent that to me says:

Apparently the Chief Diversity Office and the Multicultural Center are responsible for designating the week, and their first event will be — of course — making certain bathrooms on campus gender neutral. Keep in mind, this isn’t a club that’s putting this event on, it’s a tuition funded office at the university that now seems to be promoting transsexual ideology.

Now, the fact that this is being put on by the Multicultural Center and not, say, by a “LGBTQ Center,” tells me that Clemson hasn’t gone very far down the rabbit hole just yet. They aren’t so emphasizing LGBTQ identity that they’ve created separate offices with staff for the cause. But I’ve been told by people put on committees for the purpose of looking into the idea that a full-time Chief Diversity Officer will be hired soon, presumably with dedicated staff of their own.

If this is what the Diversity Office is already doing at Clemson, I wonder what further mischief they’ll be getting us into. This just confirms to me the way in which the concept of “diversity” on our college campuses has actually become advocacy of a certain way of thinking.

So, part of the American college experience in 2015, even at a small private large publicly funded Southern college in a conservative state, is being trained to think of sharing bathrooms with men dressed as women as an act of social justice and liberation.

Oh, Enlightenment, is there anything you can’t do?

As Douthat, Houellebecq, Ferguson, and Vodolazkin all aver, in their different ways, these scattered events that trouble us all have their roots in a fundamental breakdown of civilizational order and confidence. This is about the Western mind, but more importantly, it’s about the Western soul.

The breakdown, the crack-up, will be painful, violent, unpredictable, and long-lasting. But it’s coming. In fact, it has begun. I believe that the Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev, in his 1923 book The End of the Modern World, in which he prophesied the rise of a “New Middle Ages,” is telling us what is to emerge out of the chaos of our cultural suicide. As I wrote some time ago, quoting Berdyaev:

F]aith in the ultimate political and social salvation of mankind is quenched. We have reached settlement-day after a series of centuries during which movement was from the centre, the spiritual core of life, to the periphery, its surface and social exterior. And the more empty of religious significance social life has become, the more it has tyrannized over the general life of man. … The world needs a strong reaction from this domination by exterior things, a change back in favour of interior spiritual life, not only for the sake of individuals but for the sake of real metaphysical life itself. To many who are caught up in the web of modern activities this must sound like an invitation to suicide. But we have got to choose. The life of the spirit is either a sublime reality or an illusion: accordingly we have either to look for salvation in it rather than in the fuss of politics, or else dismiss it altogether as false. When it seems that everything is over and finished, when the earth crumbles away under our feet as it does today, when there is neither hope nor illusion, when we can see all things naked and undeceiving, then is the acceptable time for a religious quickening in the world. We are at that time… .

The Benedict Option that I keep talking about is, at bottom, an attempt at this “religious quickening” of the New Middle Age, a return to a deep and authentic life of the spirit. The Benedict Option is what Houellebecq’s François would have undertaken had he stood before the Black Madonna and answered the call he felt. He made his choice, and that choice dictated subsequent choices. We too have got to choose. Complacency = death.

Two novels — Submission and Laurus — two diagnoses of our time (one direct, the other indirect) — but only one filled with beauty, transcendence, and real hope. In my interview with Vodolazkin yesterday, he told me that got the idea for his novel Laurus by looking around him at the bleakness of daily life in Russia, and the nihilistic garbage on TV and on bookshelves, and deciding that he would undertake to write a book about a good life — that is, the life of a good man. By creating the story of a pilgrim in the Middle Ages, with all its violence, poverty, and suffering, but also the joy and purpose its people experience from their awareness of God being everywhere present and filling all things, Vodolazkin opens the door to this New Middle Age. In the book, he creates for his Russian Orthodox protagonist, Arseny, a companion on the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, an Italian Catholic named Ambrogio — this, in Vodolazkin’s words, to express his love for his Western brothers and sisters, and for Italy in particular. The journey of these men in Laurus is the journey available to all of us Christians in this time of sorrow and confusion. It is a journey of hope.

Vodolazkin, a scholar who works on medieval manuscripts at Russia’s Pushkin House, was recently in the UK giving talks about his work and his novel. From an excerpt on the TLS blog (emphases below are mine):

Laurus, which has already been translated into more than twenty languages worldwide, was Russia’s literary sensation of 2013, scooping both the Big Book and the Yasnaya Polyana awards. This, Vodolazkin’s second novel (though his debut in English), captures religious fervour in fifteenth-century Russia, tracking the life of a healer and holy fool in a postmodern synthesis of Bildungsroman, travelogue, hagiography and love story. “To quote Lermontov,” he said, “it is ‘the history of a man’s soul’.” However, when von Zitzewitz touched on the significance of the work’s subtitle (“a non-historical novel”), Vodolazkin was quick to dissociate himself from historical fiction. His is ultimately “a book about absence,” he said, “a book about modernity”. “There are two ways to write about modernity: the first is by writing about the things we have; the second, by writing about those things we no longer have.”

Laurus is an astonishing book about what we in modernity no longer have — a palpable sense of God, and of meaning and purpose in life, both individual and communal. It is about what we may have again, if we want it. Hope is memory plus desire.

UPDATE: Forgot to add that in our interview, Vodolazkin referenced a perestroika-era film, Repentance, that he described as relevant to our own time. It’s a film about the Soviet destruction of culture, and its aftermath. In the final scene, an old lady asks a woman standing in a window if the road she is on will take her to the church. No, says the woman.

“What good is a road if it doesn’t lead to church?” says the old woman, and walks on.

Yes. We have been walking this Enlightenment road for far too long, and it has us now in a dark wood.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.