The American River Disaster

After I went to the doctor in St. Francisville, I stopped by to say hello to my mother. Her friend Sue was visiting. Sue lives in Elm Park, a rural neighborhood not far from my mom’s place in Starhill. We talked about the little dog in her family killed last week by a poisonous snake. They couldn’t find the snake itself, but the vet who examined the dead dog said there were two inches between the punctures, indicating an enormous snake — no doubt either a rattlesnake or a cottonmouth.

Sue said that in her neighborhood, people have seen markedly more snakes this year, and much bigger ones on average than in years past. She added that another neighbor went out onto her back porch a few weeks back and saw a black bear in a tree. Black bears are rare in these parts, and I have never heard of one in someone’s back yard. That’s not a Louisiana thing.

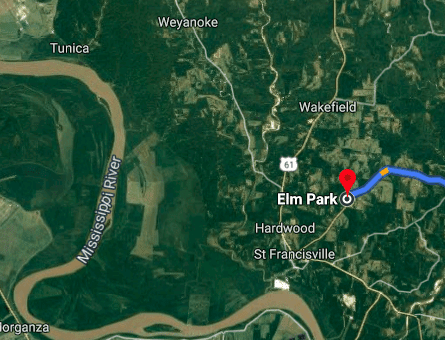

We wondered if the record flood water has anything to do with driving snakes and bears out of the swamp and into people’s yards. The Mississippi has never been so high for so long. It’s a fact that floodwaters flush snakes and all wildlife out of the inundated area, but the neighborhood where Sue lives is only a few miles from the flooded lowland parts of West Feliciana Parish. The marker on this Google satellite map is in Elm Park:

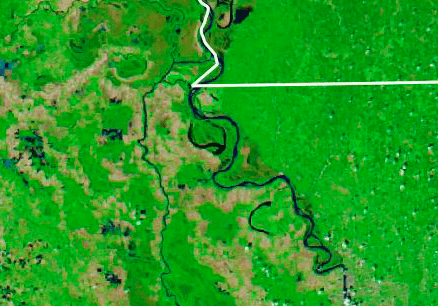

From a NASA satellite photo, here’s what the parish looks like normally (as in the Google image above):

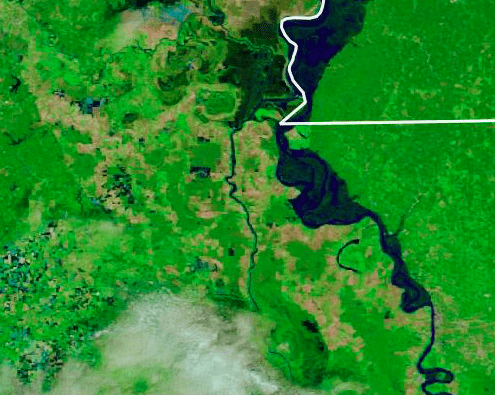

And from the same NASA satellite, here’s the flood as of mid-March. It has not improved since then, and has probably gotten worse.:

So, yeah, snakes and bears and alligators are on the move. You barely got to see any of this if you were at Walker Percy Weekend, because the town of St. Francisville is built on a bluff. It’s impossible to get down to the river landing, though. The flood water is at the foot of Catholic Hill. Most of the parish west of St. Francisville, and a ridge that runs north-northwest, is under water. It’s mostly swamp and some farmland, and is not heavily populated. But there are people who live there, and they have been suffering for most of this year.

That’s because the Mississippi has been in flood stage for the longest period on record — since January! This is causing all kinds of problems on the Mississippi, and on its tributaries. The NYT reports that shipping in the Mississippi and some of its tributaries has mostly shut down:

The devastating flooding that has submerged large parts of the Midwest and South this spring has also brought barge traffic on many of the regions’ rivers to a near standstill. The water is too high and too fast to navigate. Shipments of grains, fertilizers and construction supplies are stranded. And riverfront ports, including the ones Mr. Shell oversees in Van Buren and Fort Smith, Ark., have been overtaken by the floods and severely damaged.

As Mr. Shell surveyed the wreckage last week, anything approaching normalcy remained months, or even a year, away. To start, he would be happy just to get the power restored.

More:

Across the country’s flood-battered midsection, the farms, towns and homes consumed by the bloated waters have drawn much of the attention. But flooding has had another, less intuitive effect — crippling the nation’s essential river commerce. Water, the very thing that makes barge shipping possible in normal times, has been present in such alarming overabundance this spring that it has rendered river transportation impossible in much of the United States.

The Arkansas River has been closed to commercial traffic. So has the Illinois River, a key connection to Chicago and the Great Lakes. And so has part of the Mississippi River near St. Louis, where it crested on Sunday at its second-highest point on record, cutting off the river’s northern section from shippers to the south.

Today it was announced that this summer’s “dead zone” — where no marine life lives — in the Gulf of Mexico is going to be as big as the state of Masssachusetts. :

Annual spring rains wash the nutrients used in fertilizers and sewage into the Mississippi. That fresh water, less dense than ocean water, sits on top of the ocean, preventing oxygen from mixing through the water column. Eventually those freshwater nutrients can spur a burst of algal growth, which consumes oxygen as the plants decompose.

The resulting patch of low-oxygen waters leads to a condition called hypoxia, where animals in the area suffocate and die. Scientists estimate that this year the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico will spread for just over or just under 8,000 square miles across the continental shelf situated off the coast.

It’s the record flooding that’s making it worse, because it’s sending more fertilizer and sewage down the river.

Meanwhile, the US Army Corps of Engineers has had to open the Bonnet Carré Spillway on the Mississippi to relieve pressure on from the flood on New Orleans levees. It sends a great deal of river water into Lake Pontchartrain, from where it flows out into the Gulf. The fresh water has killed an estimated 70 percent of Mississippi’s oyster crop, and has to this point wiped out an estimated 35 percent of this year’s crab harvest. You can see from this Google map how the geography works out. The marker is on the swampy land connecting the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain (I-10 goes through it, on an elevated span). So much fresh water has been flowing through the spillway for so long that it has dramatically reduced the salinity of water off the Mississippi Coast.

The economic and ecological disaster from this endless river flooding is staggering.

Has it affected you? Tell your story.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.