Slovakia Postcard

Hello from Bratislava. It has been a busy week, and I haven’t had access to WiFi for a couple of days. I have only a short time to check in and update you on what’s happening. I hope to be able to approve comments later tonight.

I took a slow train across Austria two days ago, and really couldn’t believe how beautiful that country is. As we pulled into Vienna Hauptbanhof, I thought, “The Habsburgs chose a gorgeous country to rule for 800 years.”

I got off the train, came down from the platform to the station … and ran into my friend Eduard Habsburg, the Hungarian ambassador to the Holy See, who was about to take a train to Budapest. Imagine being in Vienna for the first time ever, and there for only two minutes when you bump into a Habsburg archduke! It really happened. See here:

At the station, Father Niall (left) and Father Petar (right) picked me up. They were my hosts. They are priests in the Family of Mary order; their priestly brother, Father Thomas Sauter, invited me to their parish in Lustenau, Austria; part two of my journey with them was to be in Nitra, Slovakia, where the Family of Mary has a mission house. The priests and I drove to Nitra, where I met some of the nuns of the order. There was an overwhelming sense of peace at the modest compound the order has in a Nitra suburb. This is palpably a place where people pray. Tucked away in my little cabin in the back garden, I slept two of the most peaceful nights I’ve had in recent memory.

I had a couple of meals with the sisters. We talked about faith, and our lives. Most of them teach in a local Catholic school. There’s one American sister among them, Sister Mary Nichole Nietzel, from Muscatine, Iowa. She’s a cook, and we had a fine time talking about kitchen things. She baked homemade cinnamon rolls for us:

I gave a talk about the Ben Op at a Catholic school, and one at a Catholic seminary (it was open to the public). Jan Banas, the Slovak translator of The Benedict Option, joined me for some Q&A translating duties. And, more importantly, he gave me a jar of his homemade apricot preserves. He had no idea that I dearly love all confiture, but apricot is my favorite:

I also was shown around the Nitra cathedral by these three lovely young ladies from the Catholic school:

I had lunch with their headmaster, and a couple of priests. Utterly fascinating conversation — all off the record, but let me tell you, these people are completely undeceived about what’s happening in the world, and why it’s happening. I wish there were some foundation with the money and the vision to bring folks like this together to share ideas and make connections.

The sisters sent me off this morning with FIVE JARS of their own apricot preserves! Even sweeter was the experience of attending mass with them this morning in their chapel, and listening to their angelic voices.

In Bratislava, I met with a group of young Catholics involved in the pro-life movement and other social movements. It was intense. One young woman contributes her time preparing young Catholics for their first communions. She said that it’s pretty discouraging to see that almost none of them want to be there in the slightest, and are only there because their grandmas bribed them by offering them a smartphone if they took the classes. In many cases, their parents never attend mass. Because their parents are not really open to Christianity, it’s all an empty social ritual for the kids.

“It’s really hard to get through to them at all,” she said.

Slovakia is one of the most Christian countries in Europe, but it’s sliding downhill here too.

One person around the table said something I’ve heard a number of times in these former communist countries: that at least under communism, you knew who the enemy was, and you knew that they were lying to you, and trying to manipulate you. Said this person: “Now we are in a time when young people can’t imagine that this ideology could be bad. They can’t see themselves being manipulated.”

Continuing this point, someone — maybe the same person; my notes aren’t clear — said that Czechoslovak society was unable to resist communism when it first appeared, because communism was “young and modern.”

He said:

“We failed. We are doing the same thing today with this new ideology. … Communism was an ideology that was clear. Now [the new ideology] comes from so many streams. When you tell young people that it’s an ideology, they don’t believe it. They can’t see it.”

Another person, a leading Catholic social activist, said that young people in Slovakia today trust not the Pope or traditional authorities to make a better world, but rather Silicon Valley figures like Mark Zuckerberg. He likened the situation today to that of the nihilists of Dostoevsky’s novel Devils. The influencers today are relatively small, but they’re nihilists, and they’re going to lead society to a real conflagration.

The conversation moved to a discussion of what, exactly, this new ideology consists of. We agreed that its very amorphousness is key to why it’s so powerful. One person said, “Nobody wants to live by any set of rules. They don’t want to live by any ideology. They think they are free.”

This person said that people aren’t really free, but they think that by doing what comes natural to them, they’re exercising liberty. One lawyer at the table called the situation “totalitarian.” I asked him why he used that word to describe a situation that was on the surface extremely different from communism.

“If you disagree with them, you are the enemy,” he said. “They enforce what they’re doing.” He meant that the embrace of so-called freedom by progressives today is a self-justifying façade for rigid ideological conformity.

Towards the end, I asked the group where they found hope. The lawyer said:

“There is something in the nature of a human being that makes you do things because they are right and good, even if you can’t expect a results from them. We have experience in Slovakia of people who came through the Second World War who did the right things, even though it was hard, and it didn’t benefit them at all.”

A Catholic activist at the table said:

“We will win. I have faith. Probably not in my lifetime. But despite this, I have to do something.”

At the very end, we had a brief discussion of a point I’ve heard several times in my travels here: total mystification as to why people will talk privately about how they think what progressives are pushing is wrong, but will never, ever take a public stand against it. This is true in the US too, but here in Slovakia, there’s more popular sentiment against the progressive social elites. Still, people remain silent. The power of US and European multinationals over the economic futures of these countries is vast. It’s about Woke Capitalism. One man tonight here told me about a friend who worked in 2015 for a US-based IT firm in Bratislava, and who was unwise enough to say on a company internal message board that he did not favor same-sex marriage (this was a discussion that had arisen on the board). Within one hour, he had been summoned to HR and fired. That story probably explains why ordinary people are afraid to speak out: they fear economic retaliation by elites. Still, the result is social change.

We talked for a few minutes about the rise of the far right. My Slovak interlocutors said that the far right party in this country, the People’s Party, has increasing support because they speak openly against liberal migration policies, abortion, and gender ideology — and don’t care what others think. Some at the table said that the People’s Party takes it too far, but they still gain support because they’re the only ones that many people trust to do what they say they’ll do.

One person at the table said that the People’s Party is the most popular party among high school students, while the harder left parties are the most popular among college students. As in other countries, political extremes are hardening.

Well, after that, it was time for lunch. My pals Juraj and Timo took me to a nearby Italian joint. After lunch, they took me to a nearby monument to Father Tomislav Kolakovic, the heroic Jesuit who came to Slovakia in 1943 to prepare a church underground to resist communism, which he expected to come after the war. My new book project will try in some way to encourage new Kolakovices to rise and prepare us for the new soft totalitarianism fast coming. Carved on the monument are the three words that were Kolakovic’s motto: “See. Judge. Act.” It was taken from Catholic social teaching. The phrase is a method of resistance that says, in effect, to observe what is happening, discern its meaning, and then act on that discernment.

See. Judge. Act. That heroic priest built an underground church movement on those simple words. Seeing is so hard in this time — and that’s the particular challenge of this moment. Timo told me that a contemporary Slovak priest said that the communist era was like darkness, but our own time is like fog. The light of faith pierced the darkness, but when light shines on fog, it can’t pierce it easily. I think that’s profound.

I came back to the hotel to do some work on the speech I’ll be delivering on Friday in Budapest, and then later headed over to Timo’s for dinner. (Remember Timo and his wife Petra from earlier this year?) I got to meet his new son, Baby Elias. Here’s a VFYT from the Krizka family table. That’s Elias sleeping in the Baby Bjorn on Mama Petra’s chest. The wine was homemade, and delicious. The arugula on the risotto was from their own garden:

After dinner, Juraj, Timo and I walked over to a pub and met some more folks from the Hanus Fellowship, a Christian civic organization, for beer and conversation. Here’s a party pic of Martina and her husband Juraj (not Juraj Sust) — Evangelical Christians who have really interesting takes on politics and culture, and who are very up to date on currents in American conservative politics:

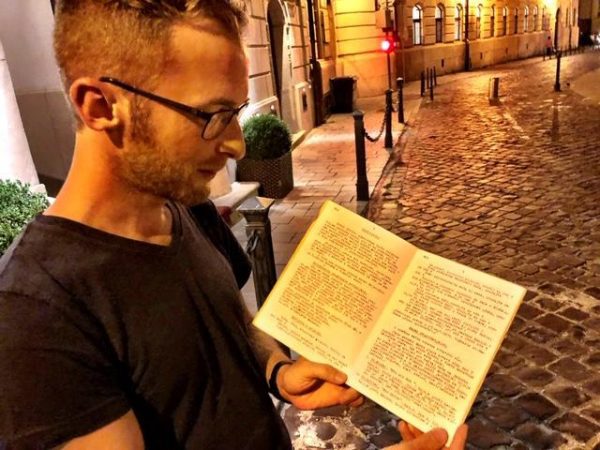

At last I had to head back, because I’m catching an early train to Budapest in the morning. Timo walked me back to my hotel, along with his pal Slavomir (I hope I’ve spelled that right), who, like Timo, is a filmmaker. Slavomir showed me a book of samizdat (underground outlaw publications) that his family found in the personal possessions of his aunt when she died. From the outside it looks like an ordinary notebook, nothing special. inside were hand-printed prayers, Bible verses, and spiritual commentaries. They had to be kept hidden under communism. Slavomir said that the courage and charity of the Open Doors Foundation, an international charity serving persecuted Christians worldwide, made the publication of a lot of Christian samizdat possible. He gave me a copy of God’s Smuggler, the memoir by the Dutchman known as Brother Andrew, who founded Open Doors in 1955.

This samizdat prayerbook is a treasure. This is how Christians and other dissidents once had to live in this country. It could happen again, you know — and it could happen to us too. We are in a culture war with people who despise the church — and who hold the cultural and economic high ground.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.