Secret Right-Wing Elizabeth Warren Crush

To be honest, it has long disappointed me that Elizabeth Warren is such a doctrinaire left winger on social issues. I would love to have a social conservative who was as red-hot on the abuse of corporate power as she is. Of course there’s no way she would ever win the Democratic nomination if she were a social conservative, nor would she be a US Senator from Massachusetts.

Back in 2011, when she announced for the Massachusetts Senate race on an anti-big business platform, I wrote in this space that she was “a Democrat I could vote for.” In 2014, observing how far gone she is on cultural leftism, I lamented that I wanted so bad for her to be good — but hey, you can’t always get what you want.

The Week‘s Matthew Walther recently wrote a piece praising her from the Right as a “forgotten reactionary.” Excerpt:

Warren’s vision of human flourishing is fundamentally a conservative one — or at least it would be if the family were still at the center of the conservative conception of politics. What she argues for is the right of families to thrive, not be the slave of financial interests, corporate power, housing monopolies, the educational establishment, or any other external force. She believes, radically, alas, in 2018, that we all have a right to food, water, housing, education, and medical care. The idea that hard-working Americans should be able to raise their children in comfort and with a sense of dignity is not, or at least should not be, the exclusive purview of any one politician or party. The fact that Warren very frequently does seem to be among the only elected officials in this country who both affirms these things and has taken the trouble to think carefully about them is a reminder that the centrism rejected by her and fellow travelers on the left and the right alike is not only noxious but omnipresent.

Warren’s economic vision of human flourishing — that is, the economic conditions she believes must be in place for people to flourish — is fundamentally conservative, in an older, more organic sense. Old-fashioned Catholic reactionaries understand exactly what she’s talking about, and so would the kind of Christian conservatives who read Wendell Berry and Crunchy Cons (which, alas, came out about 13 years too early).

Lo, Fox News star Tucker Carlson riled up the Right the other night with his tour de force criticism of right-wing free market orthodoxies (among other things).

Last night, he praised Elizabeth Warren for having written a 2003 book about how the US economy traps families. He points out that in her book, Warren made an economic case that the mass entry of women into the workplace has been a financial disaster for families. More:

Elizabeth Warren said that out loud. Nobody seemed to mind. She’d never say that today. It’s not allowed like so much else that is true and important. She can’t talk about the things that she believed 10 years ago. No modern Democrat can.

Can Republicans? In a follow-up column, Matthew Walther thinks they should, and that Tucker Carlson’s commentaries so far this year have been galvanizing. More:

If anyone had suggested to me five years ago that the most incisive public critic of capitalism in the United States would be Tucker Carlson, I would have smiled blandly and mentioned an imaginary appointment I was late for. But that is exactly what the Fox News host revealed himself to be last week with an extraordinary monologue about the state of American conservative thinking. In 15 minutes he denounced the obsession with GDP, the tolerance of payday lending and other financial pathologies, the fetishization of technology, the guru-like worship of CEOs, and the indifference to the anxieties and pathologies of the poor and the vulnerable characteristic of both of our major political parties. It was a masterpiece of political rhetoric. He ended by calling upon the GOP to re-examine its attitude towards the free market.

Carlson’s monologue is valuable because unlike so many progressive critics of our social and economic order he has gone beyond the question of the inequitable distribution of wealth to the more important one about the nature of late capitalist consumer culture and the inherently degrading effects it has had on our society. The GOP’s blinkered inability to see beyond the specifications of the new iPhone or the latest video game or the infinite variety of streaming entertainment and Chinese plastic to the spiritual poverty of suicide and drug abuse is shared with the Democratic Socialists of America, whose vision of authentic human flourishing seems to be a boutique eco-friendly version of our present consumer society. This is lipstick on a pig.

And:

It is difficult for me to understand exactly why conservatives have come around to their present uncritical attitude toward unbridled capitalism. It cannot be for electoral reasons. Survey after survey reveals that a vast majority of the American people hold views that would be described as socially conservative and economically moderate to progressive. A presidential candidate who spoke capably to both of these sets of concerns would be the greatest political force in three generations.

The answer is that for conservatives the market has become a cult. No book better explains the appeal of classical liberal economics than The Golden Bough, Sir James Frazer’s history of magic. Frazer identified certain immutable principles that have governed magical thinking throughout the ages. Among these is the imitative principle according to which a favorable outcome is obtained by mimicry — the endless chants of entrepreneurship, vague nonsense about charter schools, calls for tax cuts for people who don’t make enough money to benefit from them. There also is taboo, the primitive assumption that by not speaking the name of a thing, the thing itself will be thereby be exorcised. This is one reason that any attempt to criticize the current consensus is met with whingeing about “socialism.” This catch-all talisman is meant to protect against everything from the Cultural Revolution to modest restrictions on overdraft fees imposed at the behest of consultants.

What Walther seems to be talking about is what the political economist Philip Blond promoted a decade ago as Red Toryism, a right-wing philosophy that is socially conservative but less economically libertarian. The idea is that the neither moral libertarianism nor economic libertarianism leads to the common good.

I didn’t have this blog back then, but I was (and remain) an enthusiastic supporter of Red Toryism. At the time, the only serious question I had about it was the concern that Red Toryism’s commitment to the “common good” was a chimera, because, à la MacIntyre, we were too culturally disunited to agree on what constituted the common good. But my friend Chris Roberts challenged me, saying, “Do we really all need to agree on what constitutes virtue to agree the big banks need to be broken up?”

No, we don’t — and that’s an excellent point. The problem is that no Democrat can get elected on a “break up the banks” platform without also promising to fulfill the left-liberal agenda on LGBT and abortion. You might think that Obergefell would have reduced the pressure for marriage equality, giving the Democrats more maneuverability. Now that they have achieved the main LGBT goal, why not hold on that front and advance on economics, pulling in enough social and religious conservatives to win the presidency?

Let me explain why not. Take a look at this 2005 political typology report from the Pew Center. Mind you, this was released early into G.W. Bush’s second term. Even then, it turned out that there were twice as many on the Right who were socially conservative, but critical of big business, and who saw a role for government in helping people, as there were right-wingers who bought the standard GOP pro-business social conservative line.

The furthest extreme on the Right — not ideologically, but in terms of being a minority member of the coalition — determined the conservative party’s policy.

It was pretty much the same way on the Left, with the Democrats, though there was somewhat more parity. Seventeen percent of the Left coalition were secular economic liberals. But 24 percent were social conservatives. As with the GOP, the most extreme end of the coalition determined the party’s policy.

The great center of American politics in 2005 was with people who were broadly socially conservative, broadly skeptical of corporate power, and broadly supportive of government.

A presidential candidate who could have grabbed that center could have built a durable coalition. But there was no way the GOP was going to let anybody who didn’t buy free-market orthodoxy rise up through its ranks. Nor were the Democrats going to let a social conservative through. The establishments of both parties were captured by the people who turned out to be on the Pew extremes.

Now, that was 14 years ago — before the Iraq War became so unpopular, before the 2008 financial crash, and, heaven knows, an eon before Donald Trump descended the escalator at Trump Tower. The 2017 Pew political typology looks very different. Social conservatism is much less important to American politics than it once was. The big issues are nationalism, immigration, and the economy. On the economy, it’s interesting to see that about 40 percent of the GOP coalition are skeptical of corporate power and the current economic arrangement.

On social issues, the Democrats are more solidly liberal than the Republicans are solidly conservative, but the “Devout & Diverse” subsection of the Democratic coalition — nonwhite churchgoers — are more socially conservative. They are a relatively small percentage of the overall Democratic coalition, but in a country as closely divided as the US in 2019, it could make a difference.

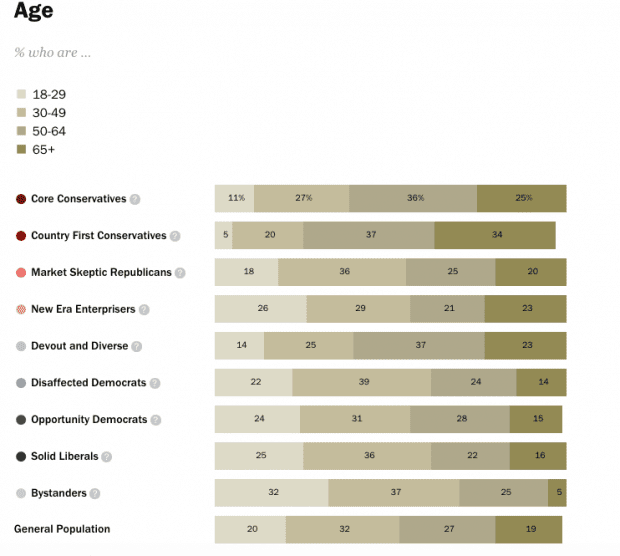

Lest we get too caught in the weeds here, I believe there is far less of a center to be claimed in American politics now than there was in 2005. Still, if you look at this snapshot of the age demographics of the US types, it’s clear where this is headed. The young are far more to the left. The only left-wing subgroup that’s interested in social conservatism at all are the Devout & Diverse, and most of them are middle-aged or older:

Pew’s further analysis shows that Millennials are far more liberal on social issues. Though conservatives like to tell ourselves that Millennials are more pro-life, the fact is that they are still broadly pro-abortion.

My point: we conservatives have decisively lost the culture war. The political future will primarily be decided on economic issues. An Elizabeth Warren Democrat who has the foresight to lay off of religious and social conservatives — not do our bidding, but simply leave us alone — might be able to peel away a good number of us. After all, if there’s no chance of socially conservative legislation ever passing, or socially liberal legislation being slowed down that much, then social and religious conservatives who are more market-skeptical are going to have different motivations to vote than we do today. Maybe a Millennial GOP politician like J.D. Vance, who supports same-sex marriage, but who is generally a social conservative, and who is relatively heterodox on economics. Here’s his response to Tucker Carlson’s monologue. Excerpt:

The market is not a Platonic deity, floating in the sky and imposing goodness and prosperity from on high. It is the creation of our choices, our laws, and our democratic process. We know, for instance, that pornography has radically altered how young boys perceive their relationships with women and sex, and that the pornography industry has acquired a lot of wealth in the process of creating and distributing that content. Just last month, we learned that a Chinese entity created the first gene-edited baby, using a technology developed in the United States. Some company, here or there, will eventually create a lot of prosperity by using this gene-editing technology (called CRISPR) in an unethical way, quite literally playing God with the most sacred power in the universe — the creation of human life. In the past few years, it has become abundantly clear that Apple — despite self-righteously refusing to cooperate with American security officials — has willingly complied with the requirements of the Chinese surveillance state, even as China builds concentration camps for dissidents and religious minorities. And, as Carlson mentioned, there are marijuana companies pushing for legalization, though we know from the Colorado experience that legalization increases use, and from other studies that use is concentrated among the lower class, causing a host of social problems in the process.

All of these entities are doing what the market demands, and in some ways, it’s hard to blame them. But shouldn’t our laws and policy make life harder for them? Or should conservatives cry “small government” every time someone suggests an intervention and stick our collective head in the sand, pretending there’s no relationship between market actors and the civil society we say we believe in?

Now, as I write this fantasia about Elizabeth Warren discovering her inner Christopher Lasch, I recognize how implausible it is. The wind is in the sails of the cultural left. But even as conservatives like me hope for someone to arise from the Right who seriously questions free-market libertarianism, I think it’s more likely that we’ll see that than that American liberalism will give birth to a figure who would be able to endorse this adaptation of a Walther paragraph:

____’s monologue is valuable because unlike so many progressive advocates of the atomized, individualized social and cultural order, he has gone beyond the question of identity politics to the more important one about the nature of late capitalist consumer culture and the inherently degrading effects it has had on our society. The Democrats’ blinkered inability to see beyond the latest episode of virtue signaling, performative wokeness, or other forms of empty political theater is shared with the core Republican activists, whose vision of authentic human flourishing seems to be a red-white-and-blue version of our present consumer society. This is lipstick on a pig.

If Elizabeth Warren could say that with credibility, I’d vote for her. But then, she would be Lasch, or Wendell Berry. The fact that the Democrats are no more likely to welcome a Lasch or a Berry into their coalition in a meaningful way than are the Republicans tells you something about American politics.

And yet, markets and a traditional moral order characterized by commitments to family, faith, community, and country can also be in very great tension with one another. The market values risk-taking and creative destruction that can be very bad for family and community, and it rewards the lowest common cultural denominator in ways that can undermine traditional morality. It seeks the largest possible consumer base in ways often hostile to national boundaries and loyalties. Modern markets can also encourage consolidation in ways that are very far from friendly to civil society. Traditional values, meanwhile, discourage the spirit of competition and self-interested ambition essential for free markets to work, and their adherents sometimes seek to enforce codes of conduct that constrain individual freedom and refuse to conceive of men and women first and foremost as consumers.

The things we value are therefore sometimes in tension with each other. When that tension arises, we have to prioritize, and that prioritization has to be guided by an idea of human flourishing that lets us roughly figure out in individual instances when and how far the demands of market competition need to be met and when and how far those of family, faith, community, or country need to be met. There is no perfect formula for doing this, obviously. But there are better and worse ways to do it, and our society has not been doing it well enough in this century, which has left a lot of ruin in a lot of people’s lives.

One key to finding this balance is to recognize that the market is a means, not an end. We should be immensely grateful for the benefits it has brought us—the ways in which it has made us better able to pursue good ends. But we should not mistake it for those ends, and so should be willing to constrain its reach when it undermines them instead of advancing them, which happens. Conservatism has ceded its economic thinking too thoroughly to libertarianism since the 1990s in a way that has caused us to forget this. It is time for that to change, and so for some rebalancing of our priorities.

True. Read it all.

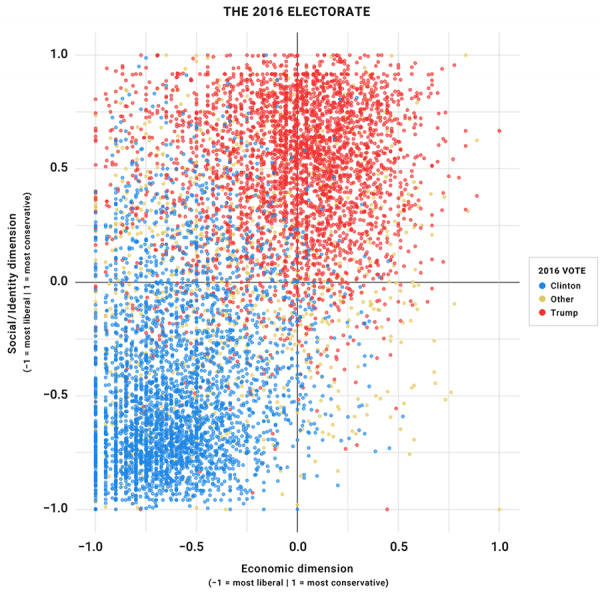

UPDATE: Reader Pyrrho posts this graphic that shows how far to the left Americans have become on economics, and how polarized on social issues. Note the economics part especially:

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.