Secession, Schism, & Catholic Civil War

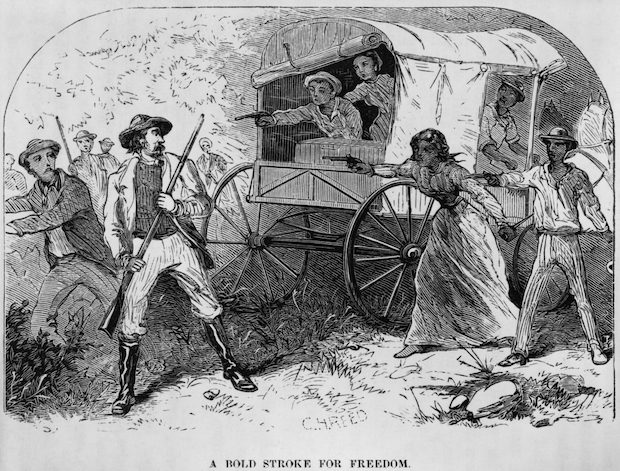

If you read nothing else today, make it Alan Jacobs’s review of a new book: The War Before The War, by Andrew Delbanco. It is a historical account of the issue of fugitive slaves, and the lead-up to the Civil War. Alan texted me yesterday to say, “There aren’t many great works of scholarship, but this is one.”

In the review, Jacobs describes what it feels like to read Delbanco’s narrative of the struggle to figure out how to hold the Union together in the face of Southern slaveholders’ intransigence. The inevitability of a terrible war becomes manifest:

You read all this with a feeling of rising horror, and not just because of the physical and mental and spiritual suffering. You feel that horror also because it becomes increasingly difficult, as the story progresses, to imagine how the even the worst of the pain could have been avoided. Not one man, or woman, knew a prudent remedy.

If the North and the South could not live with each other — the North unwilling to accept slavery, and the South unwilling to give it up — why not divorce peacefully? Because abolitionists and their allies believed that the South could establish a slaveholding empire in the Americas. Jacobs:

Something like this seems to have been Abraham Lincoln’s view as well. It is disconcerting to see him write of fugitive slaves, as he did to a friend in 1855, “I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down, and caught, and carried back to their stripes, and unrewarded toils; but I bite my lip and keep quiet.” Why keep quiet? Because Lincoln believed that over-assertive protests could lead to secession, and secession would lead to the consolidation rather than the elimination of slavery. That such evil would happen on the other side of a newly drawn national boundary would for Lincoln have been no comfort. Nor should it have been.

Delbanco’s book, according to Jacobs, draws a portrait of a nation in which there is no easy reconciliation of rival goods. It was good to seek to demolish slavery. It was good to seek to preserve the Union. What happens when you cannot have both, and when compromise is impossible? War, is what.

Jacobs:

One of the most admirable features of this truly great book is the subtlety with which Delbanco considers his story’s applicability to our own moment. Throughout the narrative proper he remains silent about the implications—except to note that the consequences of slavery for America’s black people persist to this day. But at the end of the introduction he quotes a passage written by the historian Richard Hofstadter in 1968 about comity—consideration of others, mutual regard. “Comity exists in a society,” Hofstadter writes, when “one party or interest seeks the defeat of an opposing interest on matters of policy, but at the same time seeks to avoid crushing the the opposition, denying the legitimacy of its existence or its values, or inflicting upon it extreme and gratuitous humiliations beyond the substance of the gains that are being sought.” Comity is present when “the basic humanity of the opposition is not forgotten; civility is not abandoned; the sense that a community life must be carried on after the acerbic issues of the moment have been fought over and won is seldom very far out of mind; an awareness that the opposition will someday be the government is always present.”

But how can one tell whether comity is present in one’s own society? “The reality and the value of comity can best be appreciated when we contemplate a society in which it is almost completely lacking.” The War Before the War describes how the United States of America, in the period between the composing of the Constitution and the outbreak of civil war, became such a society. And this happened not only because of wicked people who supported a wicked system—though Lord knows there were plenty of those—but also because so many Americans lost the ability to see the moral legitimacy of any proposed remedy of that wickedness other than the one they themselves embraced.

I find myself thinking this morning of this philosophical dilemma with regard to the mounting crisis within the Roman Catholic Church. Why? Because I read Alan’s review immediately after I read this superlative Anthony Esolen jeremiad about bad modern liturgy and worship aesthetics. Esolen is an orthodox Catholic and an exquisite ranter (I mean that as a sincere compliment; I share his views on liturgy). Excerpts:

Christ did come down to us in the sacrament. That was why I was there: to hear the gospel and to receive the Lord. Yet everything about this Mass made it as difficult as it possibly could have been for me to do those things. The building, the lack of art, the lousy songs, the showboating pianist and soprano, the do-nothing servers in their jammies, the replacement of the Nicene Creed with the Apostles’ Creed, the meet-and-greet, the repression of kneeling, the absent tabernacle, the Catholic Jacuzzi babbling all the while, and the applause at the conclusion of the recessional—everything said, loud and clear, “We are having fun, and this is how we like it.”

More:

“By their fruits ye shall know them,” said Jesus; fifty years is long enough for us to pass a fair judgment. Sacrosanctum Concilium is an orthodox document. But I wonder if it would have done better to have said, “Let the Mass be said sometimes in the vernacular, let there be three readings from Scripture for Sunday Masses, and let most of the priest’s prayers be said aloud.” This would have required no concession to modernist iconoclasm. Instead, we have endured fifty years of lousy church buildings, lousy music, lousy art, banal language, lousy schooling, dead and dying religious orders, and an unfaithful faithful whose imaginations are formed more by Hollywood than by the Holy One. We have been stuck in cultural and ecclesial neutral, i.e., rolling backward and downhill, or neuter, effete and infertile.

There is only one thing to do: for the future of the Church, we must build again, drawing on those cultural accomplishments that are timeless, in the service of Christ, who is the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow, in saecula saeculorum.

Now, let me be clear: chattel slavery is not the same thing as theological and liturgical disputation. Nor are conflicts that go on within a Church, and that have to do with its fundamental nature and integrity, on the same plane as things that happen within a political entity, e.g., a nation. But philosophically, there is an analogy to be discerned.

There has been an undeclared civil war within the Catholic Church for the past 50 years. I suspect that most ordinary Catholics are only dimly aware of it, but those who are engaged with church affairs certainly see it. I hardly need to go into detail about it in this space. You could say that it’s about theological “liberals” versus theological “conservatives,” but the political connotations those terms carry do not do justice to the depth and seriousness of the conflicting visions. Still, I will use them here as useful shorthand.

John Paul II and Benedict XVI frustrated many conservatives by tolerating too much liberalism within the Church. I heard it explained many times that despite their personal convictions, those pontiffs did not want to disturb the unity of the Catholic Church. It is also clearly the case that BXVI believed that he was more of a figurehead than a power-wielder.

The progressive papacy of Francis has accelerated the contradictions within the institutional Church, in part because Francis appears to be attempting to do things with doctrine (Amoris Laetitia) that some conservatives believe he cannot do. Even so, were BXVI still on the Petrine throne, there’s no doubt that the mass that so upset Anthony Esolen would still have occurred. As a Catholic, I attended more than a few masses like that. That is not Pope Francis’s fault. That is what American Catholicism is like in many places.

Why do I bring it up in connection with the Delbanco book? Because the Delbanco story, as related by Jacobs, makes me wonder if there is any valid way to resolve the conflict within Catholicism. To Catholics (and Orthodox), schism is an evil. Yet it is not the ultimate evil. The ultimate evil is apostasy. My understanding is that John Paul II wanted to keep the Catholic Church together, and hope that over time, orthodoxy would outlast and defeat heterodoxy. You might think of him as an Abraham Lincoln figure: someone who hates what his opponents are doing, but believes the greater evil would be schism.

In the case of the antebellum US, there was a cost to prizing unity. Jacobs, in his review, notes that real people (slaves) suffered real evil because Lincoln believed that the greater good required tolerating their captivity for the time being. But, as Jacobs says, Lincoln’s position was reasonable at the time. So too was John Paul’s belief, in his own time and set of circumstances.

After all, to extend the analogy, one of the evils of schism is that the schismatic church would compete against the authentic church, and perhaps lead many souls to hell. There is no guarantee that the authentic church would prevail in the world. Remember that at one point in the history of the Church, most of the Christian world was Arian. Christian orthodoxy had to fight back hard to retake the Church. Schism may be necessary, but only as a last resort.

If schism is never defensible, then Unity is more important than Truth. If that is the case, then a Church that believes that really only stands for itself, not for God. Or, the God for whom it stands as exclusive agent is nothing more than a projection of Ourselves. Not every expression of heresy requires a smackdown — prudential judgment is required — but if no expression of heresy ever requires a smackdown, then you are saying, by clear implication, that it doesn’t really matter what one believes. That nothing matters. A church that stands for nothing will not stand for long.

So, the question: At what point is schism, as bad as it is, preferable to preserving a wholly untenable status quo?

In his review, Jacobs quotes Richard Hofstadter on “comity,” saying that it entails “the sense that a community life must be carried on after the acerbic issues of the moment have been fought over and won is seldom very far out of mind.” I suppose that a tipping point could be when one or both parties becomes convinced that the “acerbic issues of the moment” threaten the core integrity, even the existence, of the community. That is, when the Other Side’s presence within the community can no longer be tolerated, because that presence is believed to destroy the community itself.

Yesterday I wrote about a Catholic reader, a new convert who suffered greatly for having converted, who was deeply scandalized by a priest holding open communion. Open communion may not seem like a big deal to people in Protestant churches that practice it, but for Catholics (and Orthodox), it is a massively important issue. It has to do with the meaning of the Eucharist, the cornerstone of the Church, and therefore with the core identity of the Church. It is not one of those things on which good Catholics can agree to disagree. And yet, Pope Francis himself once hemmed and hawed and appeared to give implicit permission to Protestants to receive Catholic communion.

Schism is to the Catholic Church what secession was to the American republic. Delbanco’s book indicates that eventually, secession was inevitable, because the differences between North and South could no longer be contained within the structure of the Republic. Nobody thinks that today, if schism came to the Catholic Church, that the Catholic parties would take up arms against each other. The “war” would manifest in non-violent ways — but make no doubt, it would indeed be a war. One can certainly sympathize with those who seek to avoid this terrible fate.

How are they going to do it, though? And what would be the triggers by which one or both parties determined that schism was the worst fate, except for apostasy — which could only be avoided by schism?

I’m not asking rhetorically. I really would like to know.

UPDATE: A reader writes:

I loved your piece on schism/civil war in the Catholic Church, but I have to address an error in its premise.

Schism, to Catholics, is not merely ecclesial division, no matter how definitive. It consists primarily of refusing to submit to the Roman pontiff. In other words, there is no circumstance in which schism would be a valid choice.

The question you posed — how to determine the point at which schism is necessary to avoid apostasy — is therefore incoherent, from a Catholic standpoint. A faithful Catholic is *obliged* to submit to the authority of the pope, no matter how corrupt or immoral his actions or how heterodox his ideas *because he is the pope*. There is no allowance in Church law for a valid rebellion; his authority is absolute and inviolable by virtue of his holding the office. Thus, any faction of Catholics who embraced schism for the sake of “avoiding apostasy” would be cutting themselves off from the Body of Christ as surely as if they had rejected the faith outright.

Hence, from a Catholic perspective, it is impossible to consider schism as a viable alternative to apostasy. For the faithful Catholic, who believes the papacy was instituted by Christ himself and imbued with the authority to teach and legislate in his name, the only alternative to both is remaining faithful to the doctrines of the Church and maintaing communion with the Pope.

So what does one do if the Pope is a charlatan? A hedonist? A tyrant? All of the above? Simple: live the Catholic life, receive the sacraments, evangelize, and pray continually and fervently for him — because no matter what he does, he is the successor of Peter.

I suspect that, by “schism,” you mean division between opposing factions who each claim legitimacy, and what you’re asking is whether there’s a point at which Catholic “conservatives” and “liberals” might seek to “save” the Church by excluding the other from the life of the Church. I think that is a discussion worth considering, because it may well be under way. By framing it in terms of schism, however, it becomes a nonstarter for a Catholic.

Thanks for that. Let me stipulate that I don’t think schism is likely in the Catholic Church. The Church, as I said, is not the same thing as a State. It’s just that I wonder what the breaking point would be, as a thought experiment.

For example, what if Pope Francis pushed farther than what a substantial number of Trads thought was permissible, and they judged that he was in heresy — thus no longer the pope? Or, what if Francis is succeeded by Pope Lenny, an arch-traditionalist, who begins swiftly reversing Francis’s initiatives, and cracks down on progressive Catholic institutions and initiatives? At what point would Spirit Of Vatican II Catholics decide that the Trads had broken with the Church, and split?

Again, it’s unlikely to happen, but my view is that it’s important to think about these things now, if only to figure out how to stop the ball rolling once it starts. I think it’s risky to say “it could never happen.” We are in uncharted waters in the Western world, with regard to religious belief.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.