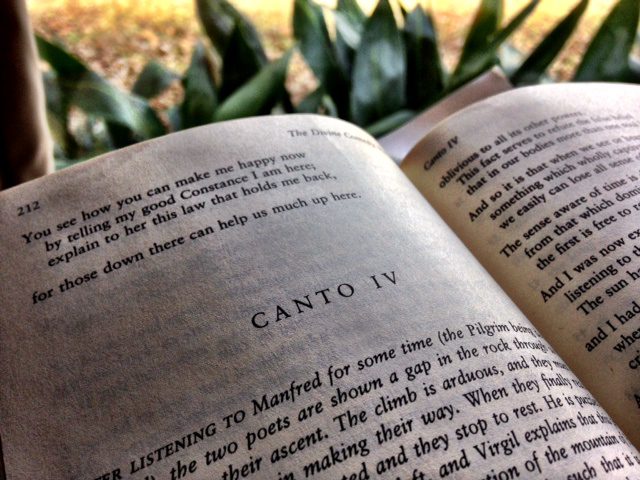

Purgatorio, Canto IV

A note of correction to yesterday’s post. I thought that Manfred et alia were Late Repentant. Hollander says that they are, in fact, the Excommunicate (though Manfred himself did repent in his final breaths). God’s mercy unleashed by this act of repentance supersedes the Church’s formal order.

Now, to Canto IV. I just returned from evening prayer at church. I am willing to bet that my priest was the only one in America who heard a confession tonight that began, “So, I was reading Dante’s Purgatorio today, and …”. But it’s true.

Before I get into what spoke most meaningfully to me about Canto IV, take a look at this passage, Virgil’s description of the climb ahead:

“This mount is not like others: at the start

it is most difficult to climb, but then,

the more one climbs the easier it becomes;

and when the slope feels gentle to the point

that climbing up would be as effortless

as floating down a river in a boat —

well then, you have arrived at the road’s end,

and there you can expect, at last, to rest.

I say no more, and what I said is true.”

This is how repentance works: the hardest steps are the first. As you advance in the spiritual life, it gets progressively easier. The entire Commedia is suffused with the medieval concept of habitus — practices that lead to the development of a certain mindset, an internal disposition inside which one lives. The climb up the mountain is about acquiring a habitus of holiness. Reading this, I reflected on the nights I’ve gotten to bedtime, and remembered that I had spent so much time burrowing in my books all day that I forgot to make the time to say my prayer rule. This Lent, I have to work harder to acquire the habit of prayer; good intentions never saved a soul.

Now, here’s why this canto informed my confession this evening. Canto IV begins with an odd speculation about the number of souls in a body (this, as a refutation of some doctrine of Plato’s obscure to me). But listen to this:

And so it is that when we see or hear

something which wholly captivates the soul,

we easily can lose all sense of time.

The sense aware of time is different

from that which dominates all of the soul:

the first is free to roam, the other bound.

Here’s the same passage in the Hollander translation:

And therefore when we see or hear a thing

that concentrates the soul,

time passes and we’re not aware of it,

for the faculty that hears the passing time

is not the one that holds the soul intent:

the one that hears is bound, the other free.

Now, this is intended to be a proof that the powers of the soul are unified. But I re-read this passage in light of the end of the canto, in which Dante meets Belacqua, an old acquaintance known for his laziness. In his earthly life, he was lazy in repentance, so here (he tells the Pilgrim) he must wait in Ante-Purgatory as long as he put off repenting — that is to say, for the equivalent of his earthly lifetime. Belacqua tells Dante that the prayers of those in a state of grace back on earth could shorten his stay.

What struck me is the teasing banter between Dante and Belacqua, and Dante’s wisecrack about Belacqua’s laziness. Remember, Dante was chastised by Cato for wasting time on the beach, and not getting on with the climb. Here is Dante now looking at Belacqua critically for his laziness. Think back, though, to how the canto starts, with Dante (the poet) explaining how one can become so absorbed in something one cares about that one can lose all track of time. Dante concedes that he had gotten so wrapped up in talking with Manfred that he had lost about three hours.

Can Dante, then, be accused of a form of laziness? When you read Purgatorio, you are constantly aware of the impulse to keep moving. Anything that delays the climb — which is to say, the journey home to God — is harmful. I think Dante’s losing himself in conversation with Manfred is a form of indolence. He doesn’t have time to sit around and talk, but that’s what he did, because he forgot himself. I may be reading too much into this because this is a form of laziness I suffer from. I’m not the kind of person who procrastinates by watching TV, playing games, or anything like that. My procrastination — that is to say, the things I do to delay getting on with what I am supposed to be doing — usually consists of stumbling into a book. I live in a house full of books, each one of them a rabbit hole down which I can and do fall down, without being fully aware of what I’m doing. It is common for me to tell my wife that I’ll be there in five minutes, and look up from my book or computer at her, steamed — and 40 minutes will have passed. The thing is, I lose all track of time when I get into a book, or I’m writing something on this blog. It doesn’t feel like I’m being lazy; I’m not reading comic books or trash fiction, but usually some serious work of history or theology. But in truth, I am being lazy, because I know that I’m supposed to be doing something else, or at least I start out that way, before I lose myself in the distraction of the book or blog entry.

Like I said, I could be reading too much into this, but this first week of Lent, as I’m searching my conscience for all the sins and tendencies to sin that keep me from doing the things I should be doing, this jumped out. I am not Belacqua, in that I am almost never still, at least not in my mind; but that does not mean I am not lazy.

In the notes to his and his wife’s translation, the Dante scholar Robert Hollander notes that Belacqua is a “Beckettian” character. Michael Robinson writes of how much Samuel Beckett relies on Dante. Excerpt:

The original Belacqua, it bears repeating, was in real life a lute maker of Florence whom Dante had known as notorious for his indolence and apathy. In the poem, he is placed on the second terrace of Ante-Purgatory, the dwelling of the late repentant who only just escaped damnation. Because they delayed their reconcilation with God until the last moment, they are obliged to wait at the foot of the mountain through a time as long as their lives on earth, enduring the indolence in which they used to indulge, before making the ascent that will prepare them for Paradise. Dante’s portrait, which humorously reveals how little this punishment disturbs Belacqua, contains much that Beckett was to use in his later work. The persistent sloth of the figure sitting with his head on his knees out of sight of the heavens that reveal the passing of time; his surly humour; the contrast between mental agility and physical lassitude; the need to live one’s life over again; and the impossibility of moving from where one is until certain preconditions have been fulfilled, are all motifs that recur in the novels and plays, and their presence denotes at first an essentially purgatorial context.

To the early heroes, who all seek what Belacqua appears to have found, ‘a limbo purged of desire,’ this existence in Ante-Purgatory represents an ideal. His namesake in More pricks than kicks is by nature ‘sinfully ignorant, bogged in indolence, asking nothing better than to stay put,’ and if he cannot lie in the shadow of a rock, he finds an acceptable substitute in a ‘lowly public’ where he is not known. He dreams, too, of a life in a lunatic asylum where he believes peace and mental freedom are to be found, for he shares with his successors in Beckett’s fiction an urge to shut himself off from the importunities of the world and of his body and to retire into the calm of his mind, so eliminating as far as possible the dualism that torments his Cartesian thinking. Malone who, dying, goes over his life yet again in fragmentary emulation of Dante’s Belacqua, even speaks of the asylum where he ends his days as ‘a little paradise.’

Ah. No doubt that Dante’s Belacqua is a smarty-pants, and that he’s not all that eager to move on up the mountain. He seems happy enough to be left alone with his thoughts. I don’t know Beckett’s work, but Robinson’s description of Belacqua’s literary children — especially the line “… an urge to shut himself off from the importunities of the world and of his body and to retire into the calm of his mind …” — cut close enough to draw blood from me.

I said I wasn’t Belacqua. Could it be that I have a lot more in common with him than I first thought?

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.