Political Cultists Of Our Time

Well, I didn’t see this coming. One of my state’s US senators, Bill Cassidy, was one of seven GOP senators who voted for Trump’s impeachment. He has sustained severe blowback here in Louisiana. I wrote this letter to the editor of the Baton Rouge paper to support him:

As a conservative voter, I have never been a Never-Trumper and though I have also never been a Donald Trump fan, I recognize he brought a much-needed shake-up to the GOP.

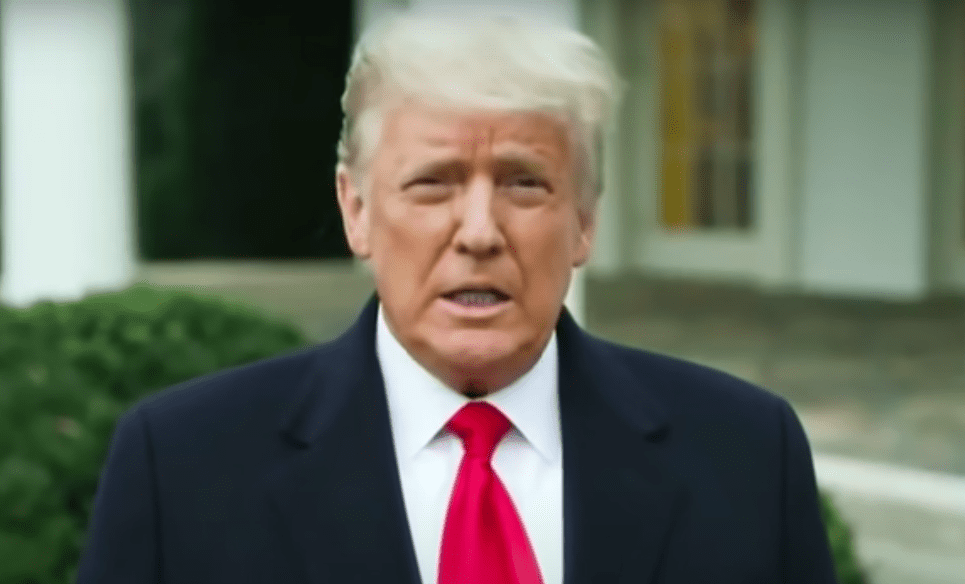

But Trump’s grotesque post-election behavior made me realize that the Never-Trumpers were more correct than I previously thought. Trump’s words and actions regarding the Jan. 6 atrocity merited impeachment and conviction. It gives me no pleasure to conclude this, but had a Democratic president done the same things, I would feel the same way.

I am also proud of Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-Baton Rouge, for his vote to convict Trump. It was a brave call.

My most recent book, “Live Not By Lies,” is about the lessons contemporary Americans can learn from the experiences of Christian dissidents under Soviet rule. The most difficult thing, but the most necessary thing, was to stand up for the truth, no matter what it cost.

Relatively few people managed to do it, but they kept their honor. I think Cassidy took the true measure of Trump and delivered a truthful verdict. I hope he wears his censure by the Louisiana GOP as a badge of honor.

Attorney General Jeff Landry blamed Cassidy for falling into a “trap laid by Democrats to have Republicans attack Republicans.” I remind Landry that principle is more important than party and truth matters more than tribe.

Besides, the reason we have a Democratic-controlled Senate today is because Trump attacked Georgia Republicans and convinced enough of his voters to stay home in the runoff as a Trump loyalty test. Trump continues to hold the GOP hostage with his threats to start a third party. Trump is tearing apart the GOP, not Cassidy and the GOP senators who voted to hold him accountable.

I am glad Trump re-oriented the GOP towards an adversarial stance to China, started no new wars and opened the ideological doors to a more populist, pro-working-class economics. I am thrilled by his judicial appointments and his defense of unborn life.

But his inability to discipline himself and focus on policy made his presidency one of lost promise. I eagerly await the rise of Republican leaders who can build on the new directions pioneered by Trump.

It is ironic that for the best of Trumpism to succeed in the future, the GOP needs to cut itself off from Trump, an amoral narcissist who disgraced himself, the presidency and his party. I am confident history will vindicate the stance for truth and honor taken by Cassidy and the six other GOP senators.

I didn’t realize the letter was going to run at all, much less today. Until I woke up this morning and received the following e-mail from a friend of 40 years:

I’d like to just let this pass, but I can’t. Support for Trump and his policies is the last straw. I can’t see a way for us to stay friends. You have broken my heart.

I fear that my early responses to questions about the conspiracy-committed have been too passive—too inadequate for the magnitude of the challenge. I’ve advised patience. Give the political moment a chance to calm. Give COVID a chance to pass. Let people come back to church, to attend the way they used to attend—in close contact with people they love.

Recreate the human connections we’ve all missed, and then let’s see if the challenge remains so urgent. Then let’s see if so many millions of Christians continue to flirt with QAnon, believe Antifa attacked the Capitol on January 6, or believe that widespread election fraud cost Trump the 2020 election. These beliefs don’t just undermine our civil society, they often exact great costs in the wrathful hearts of their adherents.

But the more I see the conspiracies play out in real life, the more concerned I grow. When large numbers of people hold beliefs with religious intensity, those beliefs not only provide them with a sense of enduring purpose, they also help them form enduring bonds of friendship and fellowship. The conspiracy isn’t just a set of intellectual convictions, it’s also a source of community. It’s the world in which they live.

Let’s put it another way: The conspiracy becomes part of their elephant.

This is a reference to a metaphor the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt uses to explain how we reason. The conscious mind, he says, is like the rider of an elephant. The elephant is the 99 percent of things going on in one’s subconscious mind, that conditions how the rider thinks. Here’s what French means:

So how does a conspiracy theory become part of the elephant? When it’s connected to the fabric of your identity, to your community, to your friendships, and to your faith.

Let’s think this through for a moment. Let’s suppose that you forward to your Aunt Edna the absolutely perfect fact check—in 900 words, her commitment to “stop the steal” crumbles into ash. Where does that leave her in her friendships? Where does that leave her in her sense of political purpose? Does it leave her disconnected from her friends in her Bible study? Does it impact her relationship with her husband? What about the online community that’s embraced her and helped her through the loneliness of the pandemic?

All of those consequences are exactly why most of the conspiracy-committed are beyond the reach of even the most potent acts of persuasion. You’re asking the rider to fight the elephant.

So, how do we persuade? We reach the elephant. If your role in another person’s life is (as you see it) the “teller of hard truths,” then you’re at an immense disadvantage when contending for a family member’s heart with the people who share the same lie, but also love them, accept them, and give them a sense of shared purpose.

Interestingly, I just finished last night the anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann’s great new book, which is about how gods become real to people. I’m going to do an epic post on it later today. She says that being embedded in a community in which theological claims are taken as real and valid is a key part of the process. It makes believing in the god more plausible.

French has some good advice for how to respond to Christian friends and family members who are caught up in this cult-like thinking. He ends with:

The longer I look at our bitter and divided culture, the more convinced I am that there are no shortcuts to cultural repair. Politics are important, but it’s relationships that will repair or destroy our land. Do we care enough about our angry relatives that we’re willing to love them back to spiritual health? The answer to that question will be more important than any media reform and any political contest. We simply cannot write off millions of Americans as beyond the reach of truth and hope.

Read the whole thing. I think French’s response is a deeply Christian one, and I don’t know of any better approach, but deep down, I think we’re probably too far gone at this point. One reason that I steered conversations with that liberal friend away from politics is because despite her intelligence and advanced education, she has always been temperamentally incapable of dealing with contrary arguments. She gets mad really fast, and stops listening. That’s regrettable, but it’s certainly possible for mature people to maintain a friendship without talking about politics, or religion, or whatever else might divide the friends.

What we have seen happen, though, on both the Left and the Right, is people lose their ability to see their opponents as human beings. People have lost their own sense of humility, and no longer consider that they might be wrong about something. As my longtime readers know, one of the most intellectually formative events for me was losing faith in the Iraq War, which I had supported without any serious doubts at all. Remembering how confident I was in my backing for the war was a bitter self-reproach. It changed me forever. I have endeavored since then to keep front to mind how fallible my own judgment — and anybody’s judgment — can be. None of us are omniscient, which means that we have to make decisions in time, based on partial information. Even the best informed of us, and the most clear-headed, can make mistakes. You had better not be arrogant in your own judgments, and merciless to those who erred, because the day will come when you will make a big mistake, and will need the mercy of those who were right when you were wrong.

As I write in Live Not By Lies, Hannah Arendt said that two signs of a pre-totalitarian society were 1) preferring lies that served one’s ideological biases to the truth, and 2) valuing loyalty over competence. We can see ample evidence of both factors on the Right and the Left today. You can argue over which side is more in thrall to these vices, but I don’t see how anyone can plausibly argue that this isn’t a widely shared problem with our public discourse — and private discourse too.

David French’s strategy only works in families and among friends who value relationships more than ideology. When you have reached a point, though, in which friends and family cut you off because they believe you are ideologically impure, how do you repair that? When you have reached point where you feel that you cannot be around certain friends and family because they will not stop ranting about their political views, and demanding that everybody agree with them, how do you fix that problem?

In 2018, David Blakenhorn wrote a piece explaining why we are so polarized. He said the fourteenth and final reason is the most important:

The growing influence of certain ways of thinking about each other. These polarizing habits of mind and heart include:

-

Favoring binary (either/or) thinking.

-

Absolutizing one’s preferred values.

-

Viewing uncertainty as a mark of weakness or sin.

-

Indulging in motivated reasoning (always and only looking for evidence that supports your side).

-

Relying on deductive logic (believing that general premises justify specific conclusions).

-

Assuming that one’s opponents are motivated by bad faith.

-

Permitting the desire for approval from an in-group (“my side”) to guide one’s thinking.

-

Succumbing intellectually and spiritually to the desire to dominate others (what Saint Augustine called libido dominandi).

-

Declining for oppositional reasons to agree on basic facts and on the meaning of evidence.

He’s right. If you think this is something that only the Other Side does, you are deluding yourself. I keep recommending the excellent 1980s-era Granada TV documentary series on the Spanish Civil War. I have cued the first episode to the point where a retired Army officer who joined the Nationalist side reflects on the state of the nation just before war broke out. Sounds familiar:

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.