The Past And Future Of Spanish Catholicism

A Spanish reader commented that he’s one of the Spaniards who has left the Church, and sent along this story from the Madrid daily El País discussing the phenomenon of secularization in Spain. Statistics show that the collapse of Christian faith is starker than any other country, except for Norway and Belgium. All of western Europe is secularizing, for reasons that also hold in Spain. But there is another reason it’s so acute in Spain. Excerpt (translated by DeepL):

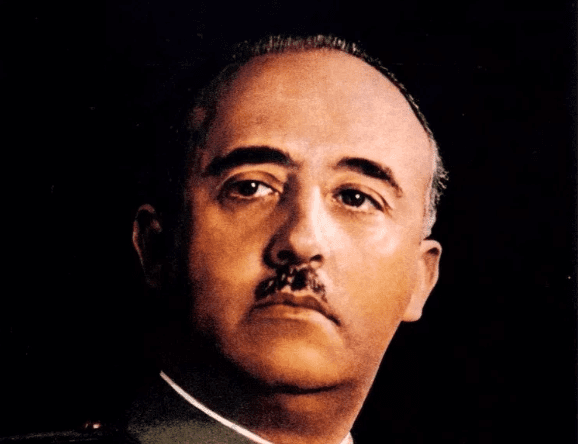

Spain and the former Communist countries share a historical trait that is reflected in the survey. Although the decline in belief in Spain contrasts with the rise in some former communist republics, the two phenomena have a common origin in the State: while socialist regimes persecuted faith, Catholic nationalism imposed it.

And that imposition resulted in boredom. In Spain, during the 40 years of dictatorship, “an affinity between religion and politics was forced,” says Josetxo Beriain, professor of sociology of religion at the Public University of Navarre. For another sociology professor, Rafael Díaz-Salazar, of the Complutense de Madrid, during those years there was “a strong association between anti-Francoism and anti-Catholicism, although not because people were against God or the Gospels. For many Spaniards, the Church was tainted with Francoism and that negative connotation led to an intense secularization in the seventies and eighties. A process that continues today: “In recent years many people are parents who have not had any socialization in religion, nor have they taken that subject,” says the expert.

I know relatively little about the Spanish Civil War, other than that it was incredibly brutal on both sides. About 15 years ago, I met a young Spanish journalist of Basque heritage. She was a practicing Catholic, but explained to me over dinner how difficult it was for her family to reconcile themselves to their faith. They had suffered under the Franco regime, not because they were leftists (they weren’t), but because they were Basques, and Franco despised Basque nationalism. The Church, she said, had been a partner of Franco’s. You see the problem.

A reader of this blog e-mailed the following to me this morning. She gave me permission to share it, as long as I kept her name off of it:

This is one of the open wounds in Spain, which will be present in the spiritual background. I didn’t want to comment on your site because for me it has a personal angle. In order to punish dissidents, the Franco government stole and gave away their children, with the participation of Catholic hospitals, among others. The numbers were in the thousands. This is called irregular adoption (also happened in Argentina):

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/01/world/europe/01franco.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/08/world/europe/spain-stolen-babies-ines-madrigal.html

In 1972, my parents left Cuba and moved to Spain for two years before securing entry to the United States, where I was born. While living Madrid, my mother had what was called a stillbirth–she never saw the baby but my father says he did. She gave birth to a girl and heard nuns say, “Oh what a beautiful baby!” then, “Oh, but this baby is dead!” And then a nun placed a gas mask on my mother’s face.

The baby could have been stolen; we don’t know. In irregular adoption cases it was a practice sometimes to show a father a baby’s corpse, kept on hand at the hospital for the purpose, so that he would accept his child was stillborn. No death certificates were issued, and at the time it was common to give mothers anesthesia by gas in labor, after which they met Baby. One of the reasons my family might have been chosen is that they planned to leave Spain and would be unlikely to follow up at a distance.

Fortunately my parents were able to carry on as a couple, though my brother obviously bears the scars spiritually and psychologically; he was five at the time, and my mother was in a spiritual trough for a good spell. My father froze then; and now he will not give any detail. He doesn’t remember the name of the hospital, and neither does she. I always assumed that my mother was traumatized by the stillbirth, and that she couldn’t accept my sister’s death. But when the story of irregular adoptions in Spain came out in the Times, I began to wonder if I my mother was right. I tried speaking with a neighbor who either had dementia or was afraid to talk. In the same way that my older relatives in Cuba are afraid to speak against the government, older people in Spain sometimes are still afraid to speak against Franco. Or were collaborators. Or who knows what.

My mother has been a devoted Baptist since childhood, so at least she did not have the pain of blaming the church for her loss. She doesn’t seem to have blamed God either; her way reminds me a lot of your sister’s. Anyway, I’m sharing to let you know the situation in Spain is complicated. Lord have mercy on us all.

I would like to know more about this, and about the political and historical background that is affecting the future of Christianity in Spain.

It is so easy for us American Christians. Earlier this month, a stash of KGB documents from Latvia were published. This outed some prominent KGB collaborators from Soviet times, including Latvia’s late Catholic cardinal and the current primate of the Orthodox Church there. Previous KGB documents have indicated that the current and previous Moscow patriarchs were KGB agents. It is horrifying to think of this. A Czech reader of this blog once told me about the pain of discovering that a beloved college chaplain was working with the secret police. We have never had to deal with anything like this evil Church-State collaboration in our history. If we had, I’m sure it would be much more difficult for Americans to keep the faith.

The religion journalist Terry Mattingly has written:

Two weeks after the 1991 upheaval that ended the Soviet era, I visited Moscow and talked privately with several veteran priests.

It’s impossible to understand the modern Russian church, one said, without grasping that it has four different kinds of leaders. A few Soviet-era bishops are not even Christian believers. Some are flawed believers who were lured into compromise by the KGB, but have never publicly confessed this. Some are believers who cooperated with the KGB, but have repented to groups of priests or believers. Finally, some never had to compromise.

“We have all four kinds,” this priest said. “That is our reality. We must live with it until God heals our church.”

That some Catholic and Orthodox religious authorities collaborated with tyranny does not negate the truth claims of either church. But it does make it harder to be open to them. It requires a lot of faith, wisdom, and strength to bear up as a believer, in the face of such realities.

I welcome your thoughts and reflections — about Spain, about the Soviet Union, about how to reconcile oneself to institutional religion in the face of such historic failures, any and all of it. I’m especially curious to hear from Spanish readers.

UPDATE: I didn’t think I had to mention here that during the Spanish Civil War, the left committed many atrocities too, especially against the Church. But I guess I do. I didn’t intend to argue about who was right and who was wrong in that war. Personally I believe the better side won … but that there were no good sides.

UPDATE.2: Grrr. I have no interest in passing judgment on the Spanish Church under Franco, or the Russian Church under the Soviets. I don’t have enough information to do so. If you are an American, and you are certain that you would have done the right thing under terrible historical circumstances, then you are probably not humble enough. I hope that I would have done the right thing … but it is much easier to say what the “right thing” was in Spain 1939, or Russia 1965, from the vantage point of the USA 2018.

In our American case, I think about the abject failure of the white Southern churches when it came to racial discrimination in the Jim Crow South, and the civil rights era. As a white Southern Christian, I hope that had I been around then, I would have chosen the righteous path. I am fairly certain I would not have done so, in part because it would have been an extremely difficult one, but far more because given the cultural realities of that time and place, even to conceive that I had a real choice in the matter would have required a massive leap of the moral imagination. I say that not to let whites of that era off the hook, but rather to temper the self-righteousness of myself and people of our own time.

UPDATE.3: I’ve just finished the first part of the Granada television documentary on the Spanish Civil War, recommended by Charles Cosimano. You can watch it all on YouTube (first part is here). It’s really good. What I’ve gleaned so far is that the proclamation of the Republic, in 1931, unleashed forces in highly hierarchical, repressed Spanish society that were impossible, ultimately, to control. The impoverished peasant masses of the countryside wanted land reform, and they wanted it right away. The republican government couldn’t deliver as quickly as they desired.

Plus, the republican government was openly anticlerical, and passed strongly anti-Church legislation. A spasm of left-wing anticlericalism — the burning of convents in 1931, while republican police forces sat by and let it happen — deeply alienated, even radicalized, Catholics.

Most crucially, political turmoil, as the parliamentary majority passed from left to right and back again, ended up radicalizing both ends against the middle. Neither the left nor the right trusted each other with power, and because democracy meant that the other side might come to power, leftists and rightists stopped believing in democracy. One rightist interviewed by Granada said that the truth is, at a certain point, both sides couldn’t stand the sight of each other. Civil war was inevitable, because the passions were red-hot on both sides, and they had all lost faith in the ability to live together, and the institutions that would have made that possible.

This seemed very ominous to me, seeing what’s happening in America today.

I strongly recommend watching the series. Though one can never really know how one would have behaved in the event, as a Christian, it seems clear to me that I would have had to have sided with the right, given how fierce and violent the hatred of the Church was from the left. But the suffering of the poor, and the system that kept their faces ground down, was intolerable. As the documentary’s first part — which deals with the five years between the Republic’s founding and the outbreak of civil war — makes clear, by the time the fighting started, there was no “both/and” middle ground left.

Again, this history makes me uneasy, thinking about the US at this moment.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.