Pascha Rage Against The Machine

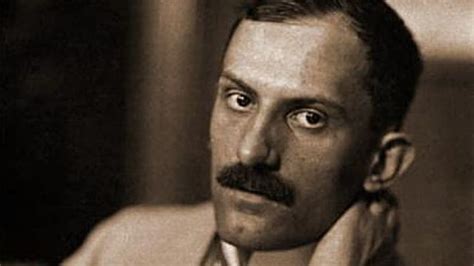

I didn’t realize until just now that I didn’t take any photos at Pascha services today! It was beautiful, but boy, how strange it was to realize that my parish back home in Baton Rouge had celebrated Pascha before we did in Budapest (because the nighttime Covid curfew meant no midnight services). Just before I left for church this morning, my Catholic friend Anna sent me this 1916 poem by the Hungarian Catholic poet Mihaly Babits. It’s called “Before Easter,” and was written in the midst of World War I.

If my lips shred to pieces – oh, courage!

this wild, wild burgeoning month of March,

drinking excitement with trees all excited,

drunk with seething, tantalising,

intoxicating,

blood-bearing, salt-scented March winds,

by grey, heavy skies,

enmeshed in the murderous mill wheel;

if my lips shred to pieces – more courage!

if bleeding raw with the song, and if

drowned by the thunderous Mill, my song

cannot be heard but merely tasted

by tasting the pain,

even so, give me yet more courage

– oceans of blood! –

bring the bitter song of bloodshed!

God, we have now heroes to glorify!

the mighty giants’ blind, bloody victories,

engines and red-hot gun barrels

busily packed with cold compresses

for their dreadful exercise:

but I will sing no paean to victory,

the rough-shod iron tread of trampling triumph

is as paltry to me,

as the deadly mill of the tyrant:

the teeming, pregnant winds of March, mighty rush,

fresh tingling blood, won’t let me salute the mad

death-machines, monstrous mills, rather

lovemaking, people, and the living

swiftly flowing, racy blood:

and if my lips are torn to shreds – give courage!

in these salty, blood-scented March winds,

by grey heavy skies,

enmeshed in the murderous mill wheel,

where mighty thrones and nations grind to dust,

century old boundaries,

iron shackles and ancient beliefs

crumble into smithereens,

flesh and the soul in double demise,

as gangrenous sores

are spat in the face of the virginal moon

and one rotation of the wheel

ends a generation:

I will not praise the mighty machine

now in March when in the air,

excited by the blustering wind

keenly we sense the moistness,

taste the sap rising, precious Magyar

blood to awaken:

my mouth, as I swallowed the sharp salty spray

flaked into sores,

saying verse is a curse of a pain now.

but if my lips shred to pieces, oh courage!

Magyar song soars in the month of March,

blood-red songs fly, ride the tempest!

I scorn the victor’s glorious fame,

the blind hero, the folk-machine,

the one, who spells death wherever he goes,

whose gaze can maim, paralyse the word,

whose touch betokens slavery,

but I’ll sing, anyone who may come,

the one, the first, who comes to pronounce the word,

the one, who first will dare to say it aloud,

thunder it, oh fearless, fearless,

that wondrous word, so waited for

by hundreds of thousands, holy,

mankind-redeeming, breath-restoring,

nation-salvaging, gate-opening,

liberating, precious word:

it’s enough! it’s enough! enough now!

come peace! come peace!

peace, oh peace again!

Let us breathe again!

Those who sleep shall rest asleep,

those who live keep coping,

the poor hero buried deep,

the poor people hoping.

Ring the churchbells to the sky,

glory, alleluia,

bring us blossoms, new-born March,

bountiful renewer!

Some shall go their work to do,

some their dead to witness,

may God give us bread and wine,

wine to bring forgiveness!

Oh peace! come peace!

we want peace again!

Let us breathe again!

The dead do not seek revenge,

the dead do not mind us.

Brothers, if we stay alive,

leave the past behind us.

Who was guilty? never ask,

plant the fields with flowers,

let us love and understand

this great world of ours:

some shall go their work to do,

some their dead to witness:

may God give us bread and wine,

drink up, to forgiveness!

It reduced me to tears. Isn’t that incredible? Part of the reason it got to me was that just last night, I was reading Norman Stone’s history of Hungary, the chapters about World War I, and what it did to this country.

But more importantly, I also thought about Paul Kingsnorth’s view that the great enemy of humanity today is The Machine. From his recent essay about Simone Weil:

Two years after Weil’s book was published, C. S. Lewis – no progressive he – had one of the characters in his novel This Hideous Strength make clear that there was no escape from this brave new world:

The poison was brewed in these West lands but it has spat itself everywhere by now. However far you went you would find the machines, the crowded cities, the empty thrones, the false writings, the barren books: men maddened with false promises and soured with true miseries, worshiping the iron works of their own hands, cut off from Earth their mother and from the Father in Heaven. You might go East so far that East became West and you returned to Britain across the great ocean, but even so you would not have come out anywhere into the light. The shadow of one dark wing is over all.

Well, the dark-winged chickens are back home now, and they are roosting on our Western shoulders, and I want to use the first few of my essays here to explore how we all got – pardon my French, Simone – covered in shit. How can we prise apart, if we can, the intersection of the Industrial Revolution, enclosure, colonialism at home and abroad, the collapse of religion, the objectification and abuse of nature, the decline of rooted and local ways of seeing, the rise of Enlightenment liberalism and the consequent flowering of me-first individualism, and the final triumph (and thus coming defeat) of the money-power of techno-capitalism? Phew. Better people than me have tried, and I won’t be able to add anything new to the mix. But I want to try and lay some of it out clumsily on this table for my own satisfaction, and I’ll be happy to be corrected by others if my knife makes the wrong cut.

However we dissect it, I believe that the heart of our global crisis – cultural, ecological and spiritual – is this ongoing process of mass uprooting. We could simply call this process modernity, which is not a time period so much as a myth (more on that another time.) But I prefer to call it the Machine, a name which I have stolen from smarter writers. I want to look into its workings (and into some of those writers) in coming essays, but for now it is enough to say that this Machine – this intersection of money power, state power and increasingly coercive and manipulative technologies – constitutes an ongoing war against roots and against limits. Its momentum is always forward, and it will not stop until it has conquered and transformed the world.

To do that, it must bulldoze everything Simone Weil valued, and everything I value too: rooted human communities, wild nature, human nature, human freedom, mythic ways of seeing, beauty, faith and all the older and truer values which until yesterday, in terms of human history, were the values of every culture on Earth. This, I think, is what the writer Arundhati Roy was evoking when she once wrote of ‘the profound, unfathomable thing we have lost.’

Because we are all uprooted now. The power of the ‘global economy’ – another euphemism for the Machine – demolishes borders and boundaries, traditions and cultures, languages and ways of seeing wherever it goes. Record numbers of people are on the move as a result, and as the population increases and climate change bites, those numbers will rise everywhere, churning cultures and nations into entirely new shapes or no shapes at all. Even if you are living where your forefathers have lived for generations, you can bet that that smartphone you gave your child will unmoor them more effectively than any bulldozer. The majority of humanity is now living in megacities, cut off from non-human nature, plugged into the Machine, controlled by it, reduced to it.

This process accelerates under its own steam because, as Weil explained, ‘whoever is uprooted himself uproots others’, thus feeding the cycle. The more of us are pulled, or pushed, away from our cultures, traditions and places – if we had them in the first place – the more we take that restlessness out with us into the world. If you have ever wondered why it is de rigeur amongst Western cultural elites to demonise roots and glorify movement, to downplay cohesion and talk up diversity, to deny links with the past and strike out instead for a future that never quite arrives – well, I’d say that this is at least part of the explanation.

Re-read that Mihaly Babits poem “Before Easter” again, and wherever Babits writes about the Machine, substitute Paul Kingsnorth’s definition. You’ll see maybe why the Babits verse moved me to tears. Babits denounced the Machine of war that destroyed nations and ancient beliefs. Our Machine is bloodless (so far), but even more destructive. And yet, Babits, a faithful Catholic, saw renewal in the spring, and in Easter.

This evening I met a new friend for a beer at Szimpla Kert, the first and most famous of Budapest’s “ruin bars.” It’s been around for almost 20 years. This Atlas Obscura post gives you the history:

Walking into Szimpla Kert in Budapest’s District VII is a bit like stumbling into the world’s most interesting junkyard. The former factory has multiple levels and a maze of different rooms, each its own curiosity shop. Now a pub, its decor is a hodgepodge of items, including a kangaroo statue, a Trabant car (in which you can sit and drink), and a bathtub cut open on one side to serve as a couch. There’s graffiti on the walls, and the exposed brick conceals nothing of the building’s structural core. Disco balls hang overhead, as do upturned chairs, and plants sprout up in its large, open-air garden. There’s a method to this madness, which is to elevate items that might be considered junk to the stature of high design.

Szimpla Kert, Budapest’s first “ruin bar,” opened in an abandoned factory in 2002, a far cry from elegantly outfitted trendy watering holes. Ruin bars have since become some of the coolest spots in the Hungarian city, seen as successful endeavors at repurposing decaying urban structures into lively communal spaces. But some of these buildings have tragic histories that cannot be overlooked, especially in District VII (also known as Erzsébetváros), which was previously Budapest’s Jewish quarter. Szimpla Kert’s space in particular was once a brick and furnace (some sources say fireplace) factory. By some accounts, the Jewish factory owners were deported during World War II, and the building went through several iterations, becoming a furniture factory and a multi-family residence, before it was vacated completely.

The past cannot be undone. But there is something special in the ruin of this factory. It’s a lovely, tattered place, with a friendly vibe. Maybe the photo from my seat at Szimpla Kert is appropriate for this post, because it’s a kind of resurrection story. It ain’t church, but there’s life there. Ring the church bells to the sky! Christ is risen! Truly he is risen! Krisztus feltamadt! Valóban feltámadt!

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.