Paradiso, Canto XXII

Finally! I packed my Dante books in a bag before the move, and it got lost in the Pile. Yesterday, I finally found the bag. Balm in Gilead!

It has been three weeks since I last posted on Paradiso. When we were last with Dante, he was in the heaven of the contemplatives, and had been startled by the quietness of that sphere. The pilgrim learned that he should not mistake silence for a lack of activity. In fact, said Beatrice, if reality were unveiled, its power and intensity would destroy him. In that sphere, Dante heard bitter denunciations of corruption in the Church by St. Peter Damian, a Church reformer. At the end of the canto, the pilgrim heard terrifying peals of thunder; this was the sound of the saints in that realm condemning Church corruption in tones that seemed to shake the universe.

Canto XXII begins with Dante running “like a little boy” back to Beatrice for protection. He is afraid. She tells him not to worry, that in heaven, “all is holy here and every act here springs from righteous zeal.

Imagine had they sung or had I smiled,

what would have happened to you then, if now

you are so shaken by a single cry?

She’s telling Dante that he cannot begin to imagine the majesty of God, and the power of the all-holy. In a gorgeous tercet, Beatrice conveys that the execution of God’s judgment always happens at the right time:

The sword of Here on High cuts not in haste

nor is it slow — except as it appears

to those who wait for it in hope or fear.

This is another admonition to Dante — and to us — to remember that he does not, and cannot, see things as they really are. Our hopes and our fears distort our perception. We may think God does not care about justice, but the truth is, He knows what He is doing. Our task is to trust in Him, even when we do not understand why He acts, or fails to act, as we think He ought. The lesson of the sphere of the Contemplatives is apophatic: that God may be known by contemplating what He is not. From the Wikipedia entry on apophatic theology:

Apophatic theology (from Ancient Greek: ἀπόφασις, from ἀπόφημι – apophēmi, “to deny”)—also known as negative theology, via negativa or via negationis[1] (Latin for “negative way” or “by way of denial”)—is a theology that attempts to describe God, the Divine Good, by negation, to speak only in terms of what may not be said about the perfect goodness that is God.[2] It stands in contrast with cataphatic theology.

A startling example can be found with theologian John Scotus Erigena (9th century): “We do not know what God is. God Himself does not know what He is because He is not anything. Literally God is not, because He transcends being.”

In brief, negative theology is an attempt to clarify religious experience and language about the Divine Good through discernment, gaining knowledge of what God is not(apophasis), rather than by describing what God is. The apophatic tradition is often, though not always, allied with the approach of mysticism, which focuses on a spontaneous or cultivated individual experience of the divine reality beyond the realm of ordinary perception, an experience often unmediated by the structures of traditional organized religion or the conditioned role-playing and learned defensive behavior of the outer man.

Peter S. Hawkins points out that this sphere disrupts the flow of the revelation in the Paradiso narrative. Dante has been going deeper and deeper into more sensual intensity, but in this sphere, everything is quiet and ascetically bare. Yet Dante does not hold the contemplative life and the active life to be antagonists. We may see the contemplatives in their monasteries as keeping still and avoiding the struggles of the “real world,” but in truth their prayers are part of the struggle, and the teaching they do by virtue of the access prayer and contemplation gives them to God enables them to be “builders of the larger society.”

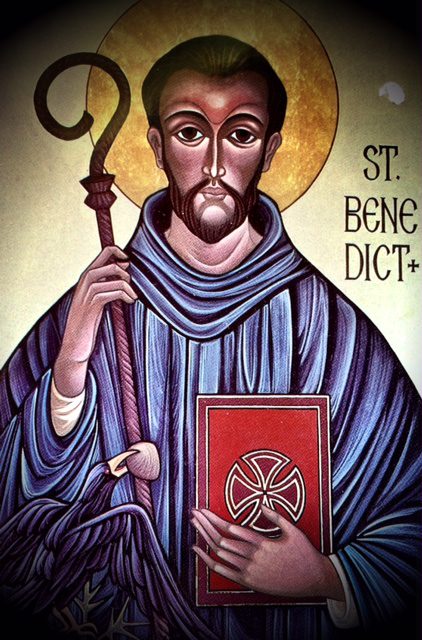

The pilgrim Dante then meets St. Benedict of Nursia, who appears to him as the brightest of a multitude of globes of fire, swarming around the Ladder of Divine Ascent. Dante asks St. Benedict if he would show to him (Dante) his face. Hawkins, in his excellent essay collection Dante’s Testaments: Essays In Scriptural Imagination, writes:

Throughout the third canticle [Paradiso], Dante has been content to see the blessed in maschera, within their veil of light; now, however, he asks to see one of his heavenly interlocutors as he essentially is, without the masquerade. This anomaly all but forces us to ask why the sphere of Saturn should be the occasion for this request and St. Benedict the one singles out. The answer lies, I think, in Dante’s understanding of the contemplative life as a formal, “regularized” preparation for the beatific vision: for the sight of God facie ad faciem, face to face. Thus far in the Commedia — indeed from the time of the Vita nuova — Datne’s yearning for such vision has been focused on Beatrice and been mediated through her. It is in her unveiled face that he first sees the “splendor of the living light eternal” (Purg. 31.139), and by means of her reflected radiance that he rises through the heaves to the Empyrean. She represents human love transfigured; the reveals how eros can be redeemed — can even become a means of ascent to God. On the other hand benedict, the father of Western monasticism, represents a radically different route to the same destination, one in which eros, rather than become transcendent, is itself transcended altogether. yet in the pilgrim’s longing to see Benedict “con imagine scoverta,” as in his earlier longing to see Beatrice unveiled, we find juxtaposed two ways by which to know God — the affirmation of a creaturely mediator and the negation of such mediation. The juxtaposition of Beatrice and Benedict here may ultimately suggest a convergence of what those two souls represent. In any event, Francesco da Buti’s fourteenth-century commentary on this moment is especially apt: “[The] contemplatives ponder the high things of God, contemplating the creature and thereby ascending to contemplate the Creator; and because the human soul is made in God’s likeness, therefore the contemplatives have the desire to see the essence of the human soul more than that of any other created thing. Thus the poet has it that such thoughts come to him in this place.” One thinks as well of St. Augustine’s conjecture, at the close of the City of God, that the blessed will see God facie ad faciem precisely by looking into one another’s faces.

St. Benedict responds to Dante’s request like this (the translation is Mark Musa’s):

… “Brother, your high desire

shall be fulfilled in the last sphere, for there

not only mine but every wish comes true;

for there, and only there, is every wish

become a perfect, ripe, entire one,

there where each part is always where it was:

that sphere is in no space, it has no pole,

and since our ladder reaches to that height,

its full extent is stolen from your sight.

Here is the same passage in the Hollander translation:

…”Brother, your lofty wish

shall find fulfillment in the highest sphere,

where all desires are fulfilled, and mine as well.

‘There only all we long for is perfected,

ripe, and entire. It is there alone

each element remains forever it in its place,

‘for it is not in space and does not turn

on poles. Our ladder mounts right up to it

and thus its top is hidden from your sight. …

This is an extraordinary, and extraordinarily beautiful, way to say that our desires can never be fulfilled in this life. Only when we are perfected in eternity, outside the realm of time, will all our desires mature and ripen to perfection. St. Benedict is telling Dante that he must be patient, and wait on God, and not allow his unfulfilled hopes to discourage him. In this way, the saint reinforces what Beatrice just told Dante about how he must accept that God moves according to His own time, not ours. Benedict also says that the mystical ladder around which he and the contemplatives swarm — the Ladder of Divine Ascent, Jacob’s Ladder — is the way to reach the highest heaven. It is a methodical way of prayer, repentance, and asceticism. It is not an elevator; it is a ladder, and all must climb it.

Then St. Benedict laments how few in the Church trouble with the Ladder and its Way to Heaven:

“But no one bothers now to raise his foot

up from the earth to climb those rungs,

and my Rule is but a waste of paper….

Then follows a prophetic denunciation of the corruption of the Benedictine monks, and all monastics, as well as the Church itself for its turning away from holiness, and squandering of the graces God gave it. It’s not only the institutional Church, it appears:

“The flesh of mortals is so weak and dissolute

that good beginnings go astray down there, undone

before the newly planted oak can bring forth acorns. …

The weakness of the flesh is not just the problem of churchmen, but everybody’s problem. We start out with the best of intentions, but if we become accustomed to indulging our fleshly desires, we fall away from grace.

Yet St. Benedict leaves Dante with a message of hope, saying that relatively minor miracles in the Bible are greater than the miracle God could work in renewing His church. The opportunity for repentance and renewal is always before us, but the more sunk in fleshly desires and worldliness we are, the more difficult it becomes to perceive it. See what Dante (the poet) is doing here? The overall message is that our passions cloud our vision, and only by making them subject to God are we able to begin to see the world as it is. This is not to say that we must always deny the flesh; the flesh is good, not evil. Scripture tells us that, and the Incarnation is the final word on that. Rather, it is to remind us that we must not let the flesh become our master. Even desires for the right thing — to see the face of God (let this be a symbol for divine reality) — can become an occasion of sin if it causes us, in our impatience, our hope, or our fear, to doubt Him and His will.

I don’t know about you, but this is a lesson that I have to keep learning, and it’s a lesson that more than a few practicing Christian friends of mine struggle to keep front to mind as well. Very few men and women in this life are monks and nuns given over to the ascetic life. We are all called to asceticism, but it is hard to crucify the flesh (the frequent Orthodox fasts are excellent training for inculcating an ascetical way of thinking and living). So much of the trouble we face in our consumerist, emotivist society comes from the desire to have what we want, and to have it all now. In Canto XXII, the poet tells us that even wanting the right things — justice, say, or love, or an extraordinary experience of God’s presence (e.g., “If He would just give me a sign, then I would believe”) — can lead us off the straight path.

A friend was telling me the other day about how he and his wife, when they first married, had good jobs, and bought the house they thought they should have. It was too much too soon, and now, twenty years on, they think of all the money they could have saved had they been more modest in their aspirations and purchases. In a spiritual sense, I think back on my early, aborted attempts to become an adult Christian. I was extremely eager for the experience of God, and had no patience for the ascetic work necessary to prepare my soul for that experience. I wanted it all, and I wanted it right then. When I didn’t get it, I fell back in despair.

Years later, as a Catholic, I was so on fire for justice to be done in the sex abuse scandal that I burned out and very nearly lost my faith entirely. It was not at all wrong to demand justice, but in retrospect, it was a serious mistake to expect it on my timetable, and it was a serious mistake to expect too much from the Church, given how weak and dissolute is the flesh of the mortal men who compose its ranks. It must seem to you readers that I ponder that dark time in my life far too much, but the truth is, the wisdom gained from that experience was won at so great a price that I fear losing my awareness of it.

As I’ve said here before, in the 1990s, when I first came into the Catholic Church — which is to say, when I became a serious Christian as an adult — I turned away from the opportunities to deepen my experience of God through doing simple things like washing dishes at the Missionaries of Charity shelter. I took the intellectual route, thinking I was going to learn about God through reading and thinking. And I did learn a lot about God that way. It wasn’t enough. St. Benedict calls for ora et labora — prayer and work, the contemplative and the active. The two dispositions combine to move a soul forward up the divine ladder. As Hawkins suggests, we might think of Beatrice and Benedict in this canto not as either-or, but as both-and, representing what all of us need to climb that ladder.

Prayer and work — “work,” meaning ascetic labors as well, such as fasting. There is no other sure way. Believe me, I’ve tried.

The canto ends with an absolutely extraordinary vision, one of the high points of the entire Commedia. After St. Benedict and the contemplatives return to the highest heaven, Dante and Beatrice begin to rise to the next heaven. The pilgrim beholds the stars — specifically the constellation Gemini (the Twins), under which he was born, and says:

O glorious stars, O light made pregnant

with a mighty power, all my talent,

whatever it may be, has you as source.

From you was risen and within you hidden

he who is the father of all mortal life

when I first breathed the Tuscan air.

Remember that the medievals believed that the stars and the planets in some sense had the power to affect lives of people on earth — that God’s will manifested itself through their movements. Dante is using the language of fertility, of generation, describing the material world as receptive of God’s fertilizing potency. The eternal and the temporal, God and the Cosmos, exist in relationship. Dante sees the natural world that gave birth to him and formed him, a baby born under the Tuscan sun, as filled with the generative power of God. Think of the vast distance between the stars and a tiny patch of ground called Tuscany, upon whose face an infant was born. The poet is telescoping reality for the reader, telling us that the galactic and the intimate are connected in a chain of relationships through which the power of the Almighty moves and gives life to all. Seen in this way, our task is to live so as to complete the circuit, so to speak. Our perfection is measured by the degree to which that power, manifested as love, flows to others and back to its Source.

And now, she speaks:

“You are so near the final blessedness,”

Beatrice then began,

“your eyes from now on shall be clear and keen.

“Thus, before you become more one with it,

look down once more and see how many heavens

I have already set beneath your feet…”

She instructs him to do this so that his heart will be “filled with joy,” and therefore properly disposed to greet the holy ones he will soon meet.

The pilgrim looks down from his heavenly perch, and sees all the places he has been through space. Crucially, he describes them in human terms. The moon isn’t the moon; it’s the “daughter of Latona,” and so forth. It’s all relational. The Dante scholar Giuseppe Mazzotta calls this “a sequence of connections as if the universe has followed the logic of generation and production, producing and reproducing itself.”

I would add that Dante sees that the universe is not cold and unfeeling, but personal, because it is the creation of a God Who loves us, and manifests himself to us through His creation. Even if we are in exile, and feel alienated from everything around us, we are nevertheless living in the presence of God’s love. A strange land can never be entirely alien to us, because it is pregnant with the power of its Creator.

All seven planets there revealed

their sizes, their velocities,

and how distant from each other their abodes.

See what’s happening here? Dante has made so much spiritual progress that he now understands how it all fits together. He can see the relationships, the sacred geometry of creation. He could not have seen it before, but his pilgrimage out of the dark wood, first with Virgil, Beatrice’s agent, and now with Beatrice, has cleansed his inner vision. The poet implies that if we will ascend the spiritual ladder, we too will come, in time, to understand the realities that now confound us.

Dante completes the canto with this marvelous image. Remember, he is near the outer edge of the universe, looking back through the solar system, his eyes coming to rest on his home planet:

as for the puny threshing-ground that drives

us mad — I, turning with the timeless Twins,

saw all of it, from hilltops to its shores.

Then, to the eyes of beauty my eyes turned.

He refers here to the Tuscans he has met in his journey through Hell and Purgatory, those who are damned or doing penitential time for their ferocity in the earthly life — that is, because they did not keep their eyes on God, but on things of the flesh, their own passions. A threshing floor is the place on which the farmer separates the wheat from the chaff; in the Gospel, this is a symbol for God’s justice, for how He will separate the good from the bad. Dante seems to be saying here that the turning of the world, and the lives we live each day, brings us closer either to good or to evil. Our mortal lives are a time of winnowing, where our eternal destinies are decided. From a cosmic perspective, our life here is “puny” — but in the same way the universal is inseparable from the particular (as the stars are to Tuscany), so too is the particular (in this case, the temporal) inseparable from eternity. What we do here in the life we are given on this earth is absolutely decisive for where we will spend eternity.

Mazzotta, in his Reading Dante, writes:

What I truly want to draw your attention to in this passage is the pronoun “us.” For all the distance implied by this poetic fiction, Dante ought to be as distant from the earth as he ever was. But the pronoun strains to have it both ways. On the one hand, Dante asserts the claim of a perspective of eternity on the world, but on the other hand, he does not want to surrender his place in time and history. He is part of humanity, part of “us,” so at the end of this great gyration through the universe, Dante claims and reclaims for himself a place within our ranks. The synthesis of the two, the claim of eternity and the sense of contingency of the self in time, is the ultimate goal of the poem and the ultimate goal of the pilgrim’s journey. [Emphasis mine — RD] That synthesis will be … the very vision of the Incarnation: the immutable structure of history and the process of time will come together.

Dante’s message to you, the reader: You matter. You matter in the sight of eternity. If you could perceive reality, you would understand how meaningless the things that most of us care about in this life are, and how ultimately meaningful are the things we lose sight of.

His eye is on the sparrow, but the sparrow, which does not have free will, does not have to have its eye on Him. That’s not how it is with us. If the eye is the window of the soul, we look out onto our own eternity. Dante contemplates for a moment the finitude of the world, then sets his eyes on the eyes of the one who will take him to God.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.