Shine a Divine Light

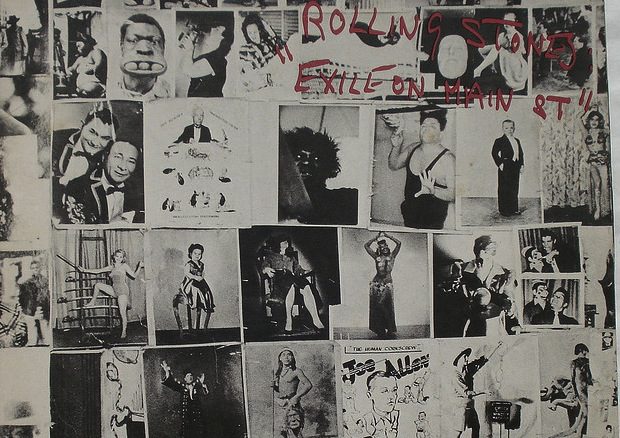

So, as one does, I spent Saturday afternoon cooking the feast for our visiting bishop, and was listening to the Rolling Stones; in my opinion, Exile on Main Street is one of the greatest musical documents of the 20th century. I was listening to a throwaway track, “I Just Want To See His Face,” the lyrics of which are here:

That’s all right, that’s all right, that’s all right.

Sometimes you feel like trouble, sometimes you feel down.

Let this music relax you mind, let this music relax you mind.

Stand up and be counted, can’t get a witness.

Sometimes you need somebody, if you have somebody to love.

Sometimes you ain’t got nobody and you want somebody to love.

Then you don’t want to walk and talk about Jesus,

You just want to see His face.

You don’t want to walk and talk about Jesus,

You just want to see His face.

And I thought: that’s the Divine Comedy, right there. It really and truly is. Buy my book How Dante Can Save Your Life if you want to know more, although I confess with regret that there is no Jaggerian exegesis between its covers. Here’s what I’m talking about in the Stones’ case, though.

The Commedia is Dante’s account of a long pilgrimage that climaxes with seeing the face of Jesus. He walks and talks about Jesus (however indirectly) through Hell, up the mountain of Purgatory, and through the levels of Heaven. The closer Dante gets to seeing Jesus in the face, the more inadequate language becomes to convey that experience. The poet Dante concedes as much here, near the beginning of Paradiso:

To soar beyond the human cannot be described

in words. Let the example be enough to one

for whom grace holds this experience in store.

[Paradiso I: 64-72]

And yet Dante must attempt to describe it in words. In so doing, he creates some of the most sublime poetry ever written — even as he helplessly concedes that the words can only crudely represent the reality he experienced. The other night, I was talking to someone about a mystical experience I had about 25 years ago, and kept apologizing for the inadequacy of my description to capture what really happened. I have never told that story without feeling the same way.

The point is that for the religious seeker, words and actions — walking and talking — which constitute the ordinary human experience of religion, are a poor substitute for direct encounter with the divine. When you are desolate, walking and talking about Jesus will not do; you want, you need, to have some sort of direct encounter. We call this sort of direct encounter “mystical,” but I think that’s a problematic distinction. “Mystical” implies a set-apart category of the experience of God, something that is given only to an elite. True, any kind of extraordinary spiritual encounter is by definition something that only happens to a relative few people, but I believe that what we call “mystical” is actually something accessible to all believers, at least in theory.

A lot of it has to do with the story you believe. Yesterday in church, we heard the Gospel lesson of the Paralytic. Here it is, from John 5:

After this there was a Jewish feast, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. Now there is in Jerusalem by the Sheep Gate a pool called Bethzatha in Aramaic, which has five covered walkways. A great number of sick, blind, lame, and paralyzed people were lying in these walkways. Now a man was there who had been disabled for thirty-eight years. When Jesus saw him lying there and when he realized that the man had been disabled a long time already, he said to him, “Do you want to become well?” The sick man answered him, “Sir, I have no one to put me into the pool when the water is stirred up. While I am trying to get into the water, someone else goes down there before me.” Jesus said to him, “Stand up! Pick up your mat and walk.” Immediately the man was healed, and he picked up his mat and started walking. (Now that day was a Sabbath.)

So the Jewish leaders said to the man who had been healed, “It is the Sabbath, and you are not permitted to carry your mat.” But he answered them, “The man who made me well said to me, ‘Pick up your mat and walk.’” They asked him, “Who is the man who said to you, ‘Pick up your mat and walk’?” But the man who had been healed did not know who it was, for Jesus had slipped out, since there was a crowd in that place.

What’s interesting here is that direct divine intervention made the man well, but the Paralytic had to accept that he could be made well for the healing to take place. The Paralytic believed that he could only be healed if he went down into the water, but because he was paralyzed, and could not get there, he assumed he was condemned to a life in bondage to suffering. He first believed that healing could be his, and then when he acted on that faith, and arose and walked, he was immediately criticized by the religious authorities for breaking the Sabbath law. They condemned this extraordinary inbreaking of God’s will into the world because it did not conform to their story.

Why do I digress? Because I believe that all of us tend to close ourselves off to the presence of God among us, and the possibility of encounter with Him. We are so busy walking and talking about Jesus that we fail to see His face when He shows it to us. We are busy Marthas when we would do well to be contemplative Marys.

In the song, Jagger sings, “Let this music relax your mind.” He’s talking about the power of art to remove the barriers of perception. I talk about the “shock of beauty” provoking an “apocalypse,” which means not “the end of the world” (though it might mean that), but rather an unveiling, an uncovering of reality. True art, if properly prepared and properly received, helps us to see things as they really are — and, perhaps, even the face of Jesus. We first have to give up the idea that walking and talking about Jesus is the same thing as encountering Jesus. As the Yiddish saying goes, “Dumplings in a dream are just a dream; they aren’t dumplings.”

For Dante, the pilgrimage through the afterlife is a progressive unveiling of the levels of reality, until he reaches the ultimate reality, the reality behind all else: the Holy Trinity. At that moment, he loses all sense of himself, and becomes fully absorbed in God’s being. He is perfected, he is fully illuminated. This is the end of Dante’s journey, and the right end of all our journeys.

Which brings us to my favorite song on Exile on Main Street: the hymn-like “Shine A Light.” Here is the audio of that song. And here are the lyrics:

Saw you stretched out in Room Ten O Nine

With a smile on your face and a tear right in your eye.

Oh, couldn’t see to get a line on you, my sweet honey love.

Berber jew’lry jangling down the street,

Make you shut your eyes at ev’ry woman that you meet.

Could not seem to get a high on you, my sweet honey love.

May the good Lord shine a light on you,

Make every song (you sing) your favorite tune.

May the good Lord shine a light on you,

Warm like the evening sun.

When you’re drunk in the alley, baby, with your clothes all torn

And your late night friends leave you in the cold gray dawn.

Just seemed too many flies on you, I just can’t brush them off.

Angels beating all their wings in time,

With smiles on their faces and a gleam right in their eyes.

Whoa, thought I heard one sigh for you,

Come on up, come on up, now, come on up now.

May the good Lord shine a light on you,

Make every song you sing your favorite tune.

May the good Lord shine a light on you,

Warm like the evening sun.

Some read this as Jagger’s attempt to wish a blessing on his debauched bandmate Brian Jones, who died from his excesses. Others read it as his hope for Keith Richards, who was consumed by drugs and excess in this period of his life. We can give a Dantean read to it, though. “Shine A Light” contrasts the darkness, disorder, and self-destruction of a ragged pilgrim, locked into his own ego (“make you shut your eyes at ev’ry woman that you meet”), with the divine harmony that God wishes for him in illumination.

Angels beating all their wings in time,

With smiles on their faces and a gleam right in their eyes.

Light, happiness, harmony: these are all images from Dante’s Paradiso. The whole place is a realm characterized by these things. The final blessedness achieved by the saints there is a cessation of longing, because all desires are fulfilled. Every song they sing is their favorite tune. From my book How Dante Can Save Your Life:

The first blessed soul the pilgrim meets is Piccarda Donati, the sister of Forese Donati, the gaunt but joyful reformed glutton. In Florence, Piccarda was a nun kidnapped from her convent by her wicked brother Corso, who forced her to marry a man to seal a political alliance.

She is on the lowest level of paradise, a sphere reserved for those who failed to be entirely faithful to their vows. This doesn’t sit right with Dante. To his way of thinking, Piccarda did not abandon her vows of her own free will; she was forced. How can she be happy with God’s decision to assign her to heaven’s farthest reaches?

Piccarda answers him “with so much gladness she seemed alight with love’s first fire.” She says:

“Brother, the power of love subdues our will so that we long for only what we have

and thirst for nothing else.“. . . And in His will is our peace.”

[Paradiso III:70–72, 85]Not only is love more important than justice, as Father Matthew once told me, but in heaven love is justice, and justice love. Accepting what you have been given with a grateful heart and not desiring anything else is the key to peace. According to the saintly Piccarda, it is not for us to question God’s plan.

Says Dante in response:

Then it was clear to me that everywhere in heaven

is Paradise, even if the grace of the highest Good

does not rain down in equal measure.

[Paradiso III:88–90]To be at peace is to cease to desire anything that God has not given. Heaven is a state of paradox in which everywhere is perfect, even though some places are at a higher degree of perfection than others. How can we speak of degrees of perfection? Because in heaven, we are perfected according to our own natures.

Piccarda, for example, bears as much divine light as her nature can accept. This reminded me of a teaching Father Matthew gave in a sermon one Sunday: “God doesn’t expect you to be St. Seraphim; he expects you to be the best version of the unique creation that is you.”

We learn from Piccarda that in the Kingdom of God, perfection is not perfect equality but perfect harmony. If I loved as I should love, I would love my family— indeed, love all people—and expect nothing in return. Inner peace depends on practicing gratitude for what I have, not complaining about what I lack.

Dante the poet uses the figure of Piccarda to illustrate how pure love doesn’t measure fairness and unfairness, doesn’t meditate on past wrongs, is not bound by envy or any earthly passion. Piccarda is free.

To be released from desire, not by having desire removed, but by having it fulfilled in God, and to dwell in music and smiles and light and love — that is Paradiso.

I think of Dante Alighieri, writing the final cantos of Paradiso from exile in Ravenna, knowing he was going to die there, without ever seeing his home again. And I imagine the divine light shining on him, a smile on his face, and a gleam right in his eye, and creating art that conveys that experience, and the possibility of that experience to his readers. People like me, stretched out in the dark wood called Room 1009. Dante sighs for you, and says, “Come on up, come on up now.”

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.