The Lost Boys

Where have the Millennial Men gone? From Bloomberg:

Nathan Butcher is 25 and, like many men his age, he isn’t working.

Weary of long days earning minimum wage, he quit his job in a pizzeria in June. He wants new employment but won’t take a gig he’ll hate. So for now, the Pittsburgh native and father to young children is living with his mother and training to become an emergency medical technician, hoping to get on the ladder toward a better life.

Ten years after the Great Recession, 25- to 34-year-old men are lagging in the workforce more than any other age and gender demographic. About 500,000 more would be punching the clock today had their employment rate returned to pre-downturn levels. Many, like Butcher, say they’re in training. Others report disability. All are missing out on a hot labor market and crucial years on the job, ones traditionally filled with the promotions and raises that build the foundation for a career.

OK, wait: this guy is only 25, and father to more than one child; he is unmarried and living at home with Mom, and won’t take a job he believes to be beneath him? What a loser.

More:

Weary of long days earning minimum wage, he quit his job in a pizzeria in June. He wants new employment but won’t take a gig he’ll hate. So for now, the Pittsburgh native and father to young children is living with his mother and training to become an emergency medical technician, hoping to get on the ladder toward a better life.

… Butcher has a high-school diploma and a resume filled with low-wage jobs from Target and Walmart to a local grocery store. He’s being selective as he searches for new work because he doesn’t want to grind out unhappy hours for unsatisfying compensation.

“I’m very quick to get frustrated when people refuse to pay me what I’m worth,” he said. His choosiness could be a generational trait, he allows. His mother worked to support her three kids, whether she liked her job or not.

“That was the template for that generation: you were either working and unhappy, or you were a mooch,” he said. “People feel that they have choice nowadays, and they do.”

Who gives Butcher that “choice”? His mother, allowing him to mooch? He complains that he is not paid what he’s “worth,” but how much is a young man worth who has two children (who live with their babymama) to support, but who is fussy about jobs? I wonder if he grew up with a father in the home.

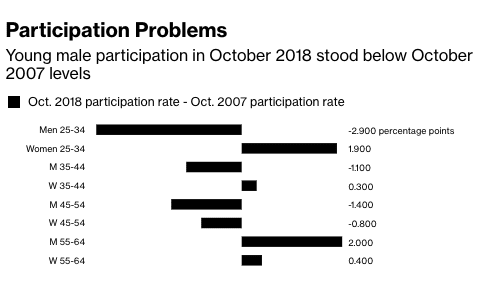

Butcher is a deeply unsympathetic figure, so much so that it might be too easy to ignore the huge social problem captured in this graphic:

That’s a staggering number. What accounts for it? More:

It’s difficult to pin down whether the demographic wants to remain on the sidelines or is kept there by a dearth of attractive options. They could be choosing to stay home or enroll in school because well paying, non-degree jobs in industries like manufacturing are fewer and further between. But it isn’t clear why lost opportunity would hit young men hardest.

The article says that opioid use and a preoccupation with video games could be factors. It doesn’t mention pornography use, but it might have done. Anecdotally, I’ve heard of middle-class, even upper middle class, males who are failing to launch. Also from the article:

“At some point, you can have a bit of an effect of a lost generation,” according to David Dorn, an economist at the University of Zurich. “If you get to the point where you’re turning 30, you’ve never held a real job and you don’t have a college education, then it is very hard to recover at that point.”

It is possible that the members of that Lost Generation will live on welfare, and anesthetize themselves with drugs and porn. Another real possibility: a demagogue will mobilize them politically for invidious purposes.

If we don’t want either outcome — and we shouldn’t — then it seems that what we as a society are generally doing now with regard to masculinity is the wrong thing. We have lost the ability to discern between manliness and machismo, between strength and thuggery. Is there anybody other than Jordan Peterson who is trying to speak liberating truths to young men like those who are at risk for dropping out? Gilbert T. Sewall, writing earlier in TAC about Jordan Peterson’s popularity, said:

Peterson insists that limits, sacrifice, and suffering color all human experience. He gives advice on how to listen, see, think, pay attention, and be self-conscious. 12 Rules for Life explores the opposing forces of chaos and order—and the gray scale in between. Humans like chaos, Peterson points out, and the novelty and promise of change. But order, not freedom, brings redemption from misery, even if it demands self-recognition of limits. In an era when youth are urged to dream crazy, Peterson gives levelheaded advice on how not to dream crazy—or at least keep crazy contained. What he writes is thus closer to the ancient moral treatises than contemporary self-help, with traces of the Tao and Seneca.

Peterson asks his audience not to beat up on itself. Yet he demands it pull its oar with a minimum of self-pity. He restates perennial questions, what it means to be human and free. Roll with human experience, he advises, it’s a good bet. “It is reasonable to do what other people have always done, unless we have a very good reason not to,” he writes. “It is reasonable for people to become educated and work and find love and have a family. That is how a culture maintains itself.” Such predispositions render Peterson a genuine conservative, concludes political philosopher Yoram Hazony in a Wall Street Journal appraisal.

Men do big things, Peterson suggests, building houses and writing books, because they crave female approval. Women inspire men. Collaterally, women seek capable, attentive, protective men. Men and women need each other. Men and women together love, build families and communities, and enforce rules and beliefs to secure order against chaos, and they fail when the rules and beliefs that undergird them collapse or prove unenforceable. Rules are not inhibiting, he reminds permissive parents terrified of being tyrants, and childhood creativity is “shockingly rare.”

Social symbols, heroes, languages, and shared folkways create coherent societies with agreed-upon mores. Contemporary cultures ignore behavior shaped by eons of biological adaptation at great peril.

Economics have a lot to do with this situation, of course, but my intuition tells me that the root of the problem with Butcher and his generation is fatherlessness — which is itself a crisis of masculinity. Now that my father is gone, and I am a father of three, I am so very, very grateful that he inculcated in me particular virtues that have helped me raise my kids. The value of work, of personal responsibility, and of standing as best you can on your own two feet. My dad, who grew up poor, had something of a chip on his shoulder about wealthy people, but also had visceral contempt for any man who would not work. (In fact, his suspicion of the wealthy was because he thought they were getting away with something by not having to work as hard as others.)

He never made much money, but he was proud that he had earned everything he had. “The world doesn’t owe you a living,” he used to say to my sister and me — this as an incentive to study and work, to learn self-discipline, and never to take anything for granted.

My father wasn’t always easy to live with, heaven knows, but had I grown up without him in the household, I might be lost today. My mother loved me dearly, but I had figured out at a young age how to manipulate her tenderness to get what I wanted. Had I not had a father in the home, I could have talked her into supporting most anything I wanted to do, because her affection for her children was so strong. She softened my dad’s sternness at times, and for that I will forever be grateful. But he balanced her in ways that were mostly healthy for us kids. Isn’t it like that in most families? Having three kids of my own, I can see clearly how a lack of either a mother or a father would put enormous challenges in front of my children — and on the single parent.

How do we as a society compensate for having deprived so many young men of real fatherhood? Is that even possible to do at the level of society? I don’t think my dad (born in 1934) was altogether unique in his generation. Men back then, at least in the South, had a pretty clear idea of what being a man meant. It was a code of honor. It was seen as shameful not to live up to it. My father grew up in an impoverished Depression-era household. His own father missed most of my dad’s childhood, because he had to be on the road making money to send back to support his family. My dad missed his father a lot, but also respected him for making the sacrifices to keep food in their mouths. I think there was no one my father hated more in this world than a man who won’t take care of his children. It’s hard to grow up in a household like I did and not have instinctive contempt for young men like Nathan Butcher.

I doubt that the scorn of moralistic people like me will do the hundreds of thousands of Nathan Butchers of the world much good. But part of me wonders if there is any motivating factor capable of reaching these young men stronger than shame. At what point is the compassionate thing to do to say, “Get off your ass and get a job, and stick to that job, even if you hate it. You can’t be a boy forever”?

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.