Exhausted By Political Takes

It probably sounds silly now, but up until that point I had not understood what it meant to wield language strategically. I had understood language as an instrument of expression, of explanation and of description. I had known, of course, that language could be used to make an argument. My professors in the Brown English department had worked hard to convince me that language could even betray arguments their users had not intended. But what I learned at the Center was something different. The paragraph, the sentence, even the individual word revealed themselves as potential foot soldiers in the battle for public opinion and political power. It was imperative to always be pushing forward, onto new ground. There was no other goal besides winning.

That was the message I absorbed, anyway, first from the senior staff member and then later by osmosis from the public-relations people whose offices were across the hall from the communications cubicles. It is not exactly how the senior staff member put it. She implied that my use of language should be honed in order to communicate the facts as clearly and convincingly as possible. It would have gone without saying at the think tank, except we said it all the time, that we were proud members of what Karl Rove had reportedly derided as the “reality-based community.” To be a progressive at the Center for American Progress was to be on the side of reality. It was also, I learned, to believe reality was on one’s side. This was very convenient. It meant there were no questions, only answers. Our job was to package those answers as appealingly as possible.

More:

Even after George W. Bush had won re-election, a development that might have led to some measure of self-examination, there still appeared to be strict limits regarding what kinds of policy ideas would be considered worthy of serious consideration—limits set mainly by the think tank’s political strategists. In the years after I left the Center, I would often hear the policy academics who worked there referred to disparagingly as “technocrats.” The label was meant to convey the accusation that these figures, who pretended to solve problems chiefly in their technical aspect—that is, without regard for ideology—were in fact adherents to the anti-political ideology of technocracy or “rule by experts.” While this might be a passable description of certain politicians whom the think tank supported, the think tank, from where I sat at least, looked to suffer from something like the opposite problem: the experts were hardly even trusted to rule themselves. Far from being encouraged to conduct independent or innovative research, their projects appeared explicitly designed to reinforce the Center’s pre-existing convictions about what it took to achieve electoral success. And they were trusted even less than the communications staff—meaning me, who knew nothing—to describe or explain their work to the outside world. After all, they may not have learned how to stay on message.

Washington, DC: where innovative thinking goes to die.

Baskin goes on to work in the world of small, left-of-center magazines. He discovers, though, that they are pretty much an intellectually sophisticated version of what he left behind in DC: entities that prioritize instrumentalizing thinking for the sake of political goals. More:

I was coming to appreciate an old problem for the “intellectual of the left.” This problem is so old, and has been addressed unsuccessfully by so many very smart people, that we are probably justified in considering it to be irresolvable. To state it as simply as possible, the left intellectual typically advocates for a world that would not include many of the privileges or sensibilities (partly a product of the privileges) on which her status as an intellectual depends. These privileges may be, and often are, economic, but this is not their only or their most consequential form. Their chief form is cultural. The intellectual of the left is almost always a person of remarkably high education, not just in the sense of having fancy credentials, which many rich people who are not cultural elites also have, but also on account of their appetite for forms of art and argument that many they claim to speak for do not understand and would not agree with if they did. They write long, complicated articles for magazines that those with lesser educations, or who do not share their cultural sensibilities, would never read. They claim to speak for the underclasses, and yet they give voice to hardly anyone who has not emancipated themselves culturally from these classes in their pages.

I would love to read something by an intellectual of the right, embedded in that DC world, talking about the cultural differences between the intellectual leadership class and the people who vote conservative. When I was part of that world over 15 years ago, one of its leading lights advised me to “vote Right, live Left” — which in today’s vernacular, would be “vote Red, live Blue.” His point is that there is no reason why advocating for conservative political goals should require us to take up NASCAR and other enthusiasms of the GOP base. He’s right, of course. The problem with that, as Baskin notes in his analysis above, is that losing a gut cultural connection with the people for whom you are advocating could easily lead intellectual elites to assume that what they think is good for the masses actually is good for the masses, or at least what the masses want.

This is why, despite the best efforts of conservative elites, we have Trump.

Baskin goes on to talk about why the magazine for which he now writes, The Point, is on the left, but small-c catholic in its tastes:

It has also meant publishing a wider range of political perspectives than would usually be housed in one publication. This is not because we seek to be “centrists,” or because we are committed to some fantasy of objectivity. It is because we believe there are still readers who are more interested in having their ideas tested than in having them validated or confirmed, ones who know from their own experience that the mind has not only principles and positions but also, as the old cliché goes, a life. If the Jacobin slogan indicates a political truth, it inverts what we take to be an intellectual one: Ideas Need Resistance.

This is true even, and perhaps especially, of political ideas. Our political conversation today suffers from hardly anything so much as a refusal of anyone to admit the blind spots and weaknesses of their ideas, the extent to which they fail to tell the whole truth about society or even about their own lives. In our eagerness to advance what we see as the common good, we rush to cover over what we share in common with those who disagree with us, including the facts of our mutual vulnerability and ignorance, our incapacity to ever truly know what is right or good “in the last analysis.” This is the real risk of the strategic approach to communication that sometimes goes by the name of “political correctness”: not that it asks that we choose our words carefully but that it becomes yet another tactic for denying, when it is inconvenient for the ideology we identify with, what is happening right in front of our eyes—and therefore another index of our alienation from our own forms of political expression. The journalist Michael Lewis, embedded with the White House press corps for an article published in Bloomberg in February, observed that a “zero-sum” approach is spreading throughout political media, such that every story is immediately interpreted according to who it is good or bad for, then discarded, often before anyone has paused to consider what is actually happening in the story. In this sense, the media mimics the president they obsessively cover, who as a candidate had promised his supporters that if they elected him they would “win so much you’ll get tired of winning.” Trump has always been the cartoon king of zero-sum communication—“No collusion!” he tweets in response to the news that thirteen Russians are being indicted—a person to whom one senses news is only real to the extent that he can interpret it as helping him or hurting his enemies. But Lewis is surely right that the zero-sum approach has become pervasive across the culture. I certainly see it in the corner where I spend a lot of my time, at the intersection of academia and little magazines.

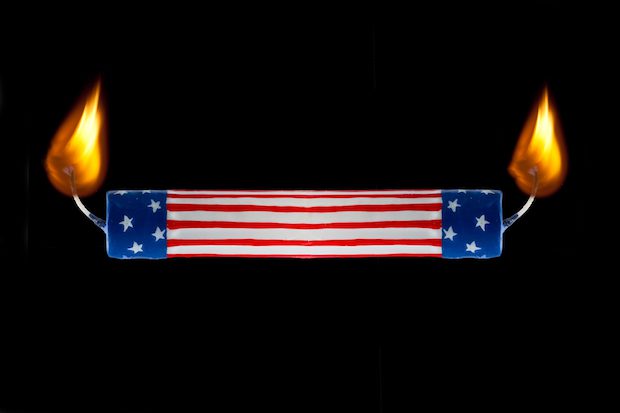

Read the whole thing. The essay is titled “Tired of Winning,” after a line of Trump’s, but it’s used here to convey the intellectual exhaustion from having to kern everything in life to fit a useful political narrative. There is far, far more to life than politics! People who cannot conceive of life in anything other than political terms are, well, tiresome.

In his essay, Baskin says that Think Progress, the website started by the center for which he used to work, has become one of the most successful advocacy sites on the left. You ever tried to read Think Progress? It’s terrible. It’s about advocacy, full stop. Reading it is like confronting the daily online newsletter of the sheep in Orwell’s Animal Farm — the ones who can be exhorted in a trice to bleat, “Four legs good! Two legs bad!” And yes, the right has the same kind of publications and institutions.

Why do people who value independent thought go to work for such places? I’m not asking in a trollish way. I’m asking in a Jon Baskin way.

One of the things I cherish about The American Conservative is that its editors have never told me what to write. It’s a place where they encourage me to follow my thoughts, and see where they lead. I was so thrilled to learn that Benjamin Schwarz has been promoted to be our editor in chief. He’s that kind of conservative.

(By the way, I learned about this essay via Prufrock, the morning aggregator that Micah Mattix does under the Weekly Standard‘s aegis. I’m not sure how you can subscribe; there is no link to the “Subscribe here” line at the end of the page, e.g., here.)

UPDATE: Subscribe to Prufrock here. You won’t regret it. It’s very eclectic.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.