Houellebecq & The Benedict Option

What a pleasant buongiorno this is: another column about The Benedict Option by Sandro Magister, the great Vaticanist. In fact, he hands his column over today to church historian Roberto Pertici, who discusses the Ben Op in the context of the Youth Synod underway now at the Vatican. Pertici believes that The Benedict Option is more relevant to the youth, and therefore to the future of the Church, than the official pageantries taking up this Roman autumn.

I especially love this part of Pertici’s analysis:

In his book Dreher never cites the work of Michel Houellebecq, the great and controversial French writer, but he has repeatedly stated that he considers him an interlocutor in his work. I believe that he is right: in his best novels there is more history and philosophy than in many professorial volumes (one could read in this regard the book by Louis Betty “Without God. Michel Houellebecq and Materialist Horror” released in 2016).

His 1998 novel “The Elementary Particles” revolves around the concept of “metaphysical mutation.” Houellebecq writes: “In the history of humanity, metaphysical mutations – meaning the radical and global transformations of the worldview adopted by the majority – are rather rare. […] As soon as it is produced, the metaphysical mutation develops until it reaches its extreme consequences, without ever encountering resistance. Imperturbable, it overturns economic and political systems, aesthetic judgments, social hierarchies. There are no forces capable of interrupting its course, neither human nor of another kind, apart from the advent of a new metaphysical mutation.”

One first example that the French author gives is that of the advent of Christianity: in those centuries “the Roman empire was at the summit of its power; perfectly organized, it dominated the known universe; its technological and military superiority was unrivaled. And yet it had no hope.”

Analogously at the end of what we call the Middle Ages: “At the advent of modern science, medieval Christianity constituted a complete system of comprehension of man and of the universe; it served as a foundation for governing the people, produced knowledge and works, decided both peace and war, organized the production and division of wealth. All that did not succeed in preventing the collapse.”

Since then there has been the gradual assertion of what the writer calls “the materialist age.” Its conclusive moment is precisely in the “sexual revolution,” the development of which in France and in the world is followed by Houellebecq, almost year by year, with a series of extremely evocative notations: in the novel, it is personified in the figure of Janine Ceccaldi, the mother of the two protagonists. Janine, born in 1928, belongs to the “dispiriting category of forerunners”: those who “have a mere role as historical accelerator – generally an accelerator of a historical decomposition – without ever being able to give a new direction to events.”

Houellebecq had already dealt with the “sexual revolution” in his 1994 debut novel “Extension du domaine de la lutte,” in English “Whatever.” This is not the place to explore its analysis, suffice it to say that for the French writer it is the extension to the sexual sphere of the unbridled competition and economic individualism typical of the pure market society. That is, there exists a parallel between uncontrolled economic liberalism and absolute sexual liberalism: both produce phenomena of absolute impoverishment, widespread forms of exclusion.

The proponents of hypermodernity are convinced that they have the world in their hands. Who knows, however, if they may be like the pagans of the late empire or the scholastic philosophers of the early modern era: that among the possible hypotheses there may be a change of paradigm, a new “metaphysical mutation.”

The readers of “The Elementary Particles” know how this happens, in what direction it develops and who is – so to speak – its promoter: it is certainly not the one desired by Dreher. But beyond the narrative plot (it must always be remembered that we are talking about a novelist and poet, not a professional historian or philosopher), it is important to register his rejection of a continuous and inexorable journey of history, of a unidirectional conception of historical development, which is instead typical of “progressivism,” including the Catholic form. Ruptures are possible, and what seems to triumph today, as has been stated, can decline.

I don’t know to what extent Dreher has been influenced by this vision, but at the foundation of “The Benedict Option” one perceives something analogous. It is not to be taken for granted that the era that began with the “metaphysical mutation” of the first centuries of the modern era and has led to the current Western dechristianization is “forever.” The complete unfolding of its consequences could lead to a new rupture: one must be ready for this moment. This is why it is important to preserve the Christian heritage intact in order to be able to present it again in a mutated world: unlike Houellebecq, the American writer maintains that this is possible. To preserve it by working together with the humanity of our time – Dreher says – not in idleness. At the bottom of his vision there does not seem to be, therefore, a disconsolate pessimism or – as has been said – the perception of a state of siege: but the reasonable hope for a revival.

Yes, that’s exactly right! I believe that the vision of The Benedict Option is realistic, and therefore hopeful — much more hopeful than the deconstruction of traditional Christianity underway in Rome and elsewhere. St. Benedict did not set out to “save the West.” He only wanted to find a way to serve God faithfully in a time of great chaos and anxiety, over the collapse of the Roman system. Every good thing that followed for Western civilization from Benedict’s work came because he and his men put the search for God first.

As Marco Sermarini, the great Benedict Option Catholic living on the Adriatic puts it in my book:

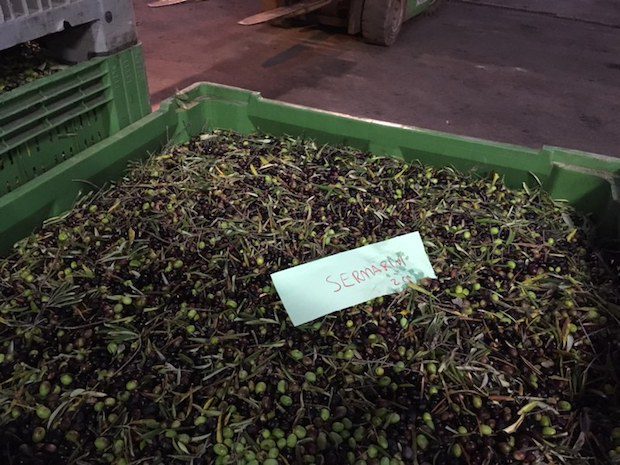

Driving through the achingly beautiful towns and fields overlooking the Adriatic, Marco pulled his SUV over on the side of a narrow country road and led me to a steeply plunging hillside. It was covered with olive trees. This was the Sermarini family olive grove. As a boy, Marco’s ninety-one-year-old father helped his own father harvest olives from these trees. Marco was raised doing the same, and now he and his own children collect olives yearly and press their oil for the family’s use.

This, I said to Marco, is stability.

He shrugged, then looked out pensively over his trees.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen next in life, but in the meantime, we have to fight for the good,” he told me. “The possibility of saving the good things in the world is only that: a possibility. We have to take the chances we have to set a rock in the earth and to keep this rock steady.”

We walked back to the SUV, climbed in, and drove on. My friend continued to wax philosophical about stability in a world of change.

“Nothing we make in this life will be eternal, but we have to build them as if they will be eternal,” Marco continued. “That’s what God wants. If you promise yourself to a woman for a lifetime, that is a way of making the eternal present here in time.”

We have to go forward in confidence that the little things we do might, in time, grow into mighty works, he explained. It’s all up to God. All we can do is our very best to serve him.

Sometimes Marco lies in bed at night, worrying that his efforts, and the efforts of his little Christian community, won’t amount to much in the face of so much opposition. He is anxious that the current will be too strong to resist and will tear them apart.

“I know from the olive trees that some years we will have a big harvest, and other years we will take few,” he said. “The monks, when they brought agriculture to this place a thousand years ago, they taught our ancestors that there are times when we have to save seed. That’s why I think we have to walk on this road of Saint Benedict, in this Benedict Option. This is a season for saving the seed. If we don’t save the seed now, we won’t have a harvest in the years to come.”

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.