Hilary Mantel’s Cursed Childhood

I’ve not read English novelist Hillary Mantel’s historical fiction, but quite a number of people have. Writer Patricia Snow is one of them, and in a chilling (really) First Things essay, Snow analyzes the characters in Mantel’s two novels set in Tudor England, and draws out the connections between them and Mantel’s traumatic childhood. The essay begins like this:

By now, everyone who reads contemporary fiction will have heard of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, Hilary Mantel’s acclaimed historical novels about Thomas Cromwell, the powerful advisor to Henry VIII who all but single-handedly disestablished the Catholic Church in England. Anathema to many Catholics on account of their sympathetic portrayal of Cromwell, the books have been runaway bestsellers, were awarded the Booker Prize (twice), and have been successfully adapted for both stage and screen. Psychologically persuasive and prodigiously self-assured, they are examples of what can happen when an artist, who has been honing her craft in the meantime, finds or invents material that turns out to be the perfect vehicle for her powers. In Mantel’s case, when she began writing about Cromwell, by her own account she was “filled with glee and a sense of power,” a conviction that everything in her life had prepared her for this.

The Catholic childhood Mantel lived in the north of England was a nightmare. Snow draws extensively on Mantel’s own published memoir to discuss how its characters and themes shaped Mantel’s fiction. You don’t need to know Mantel’s work — again, I don’t — to appreciate the insight in Snow’s speculative analysis, in particular why Mantel may have made Thomas Cromwell the dark, dark hero of her novels.

What knocks the reader for a loop is this passage in the essay, which quotes from Mantel’s 2004 memoir, Giving Up The Ghost. Jack is the lover her mother takes, and moves into the family home, exiling Mantel’s father down the hall in his own home:

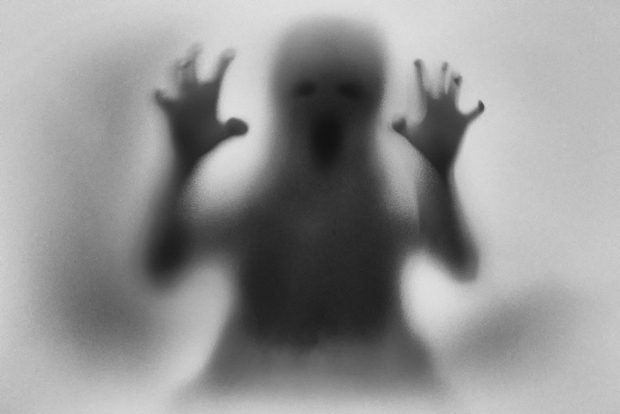

In Mantel’s memoir, after Jack moves in with her mother, their house slowly fills with unseen, malevolent presences. It is not only the child who is aware of this, but the adults and adult visitors as well. Objects disappear; gusts of wind roar through the rooms; doors slam and their dogs cry with fear in the night. On weekends, the sallow, perspiration-soaked Jack hacks at the undergrowth in the overgrown garden, opening a view to the fields and the moors beyond.

Mantel is seven, going on eight. A pious, scrupulous child, she fears more than other sins blasphemy and inflicting brain damage, which would happen, she explains, if you were to drop a baby before the soft bones of his skull had closed. You might think, she confides elsewhere, that she would have asked God to show himself and put an end to the events in her home. But in her words, she was spiritually ambitious and had her own understanding of grace. (“By not asking for it, you get it.”) Rejecting the prayer of petition, and the risks that accompany it (“Because if it didn’t work . . .”), she simply waits. For a year, she carries around inside herself an empty, waiting space for God, a space that sounds ominously like what Malachi Martin calls an “aspiring vacuum” in his book about demonic possession.

It is the morning of an ordinary day. Mantel is playing by herself in the backyard when something causes her to look up, some trick of the light. Her eyes are drawn to a spot beyond the yard, in the garden that Jack has been clearing.

[The spot] is, let us say, some fifty yards away, among coarse grass, weeds and bracken. I can’t see anything, not exactly see: except the faintest movement, a ripple, a disturbance of the air. I can sense a spiral, like flies; but it is not flies. There is nothing to see. There is nothing to smell. There is nothing to hear. But its motion, its insolent shift, makes my stomach heave. . . . It is as high as a child of two. Its depth is a foot, fifteen inches. The air stirs around it, invisibly. I am cold, and rinsed by nausea. I cannot move. I am shaking. . . . I beg it, stay away, stay away. Within the space of a thought it is inside me, and has set up a sick resonance within my bones and in all the cavities of my body.Mantel’s first thought is that she has seen the devil, who did not intend to reveal himself. She knows from experience that if you witness other people’s mistakes, and they know it, they will make you pay. Terrified, she flees to the house as “grace runs away from [her] . . . like liquid from a corpse.” In the days and years afterwards, she is always more or less afraid and ashamed. After her encounter in the garden with what she calls elsewhere a “slow-moving sinister aggregation of cells . . . like a cancer looking for a host,” wherever she goes and whatever she does, what she has seen accompanies her: “a body inside my body . . . budding and malign.”

In that moment, she was possessed. And that “budding and malign” spiritual cancer has never left her. Demons don’t generally depart of their own accord. Snow writes:

If a testimony, traditionally understood, is the story of a life-changing encounter with God, Giving Up the Ghost is an anti-testimony, the centerpiece of which is a life-changing encounter with a demon. Yet it never seems to occur to Mantel to discuss her situation with a priest.

In fact, Mantel remains to this day bitterly anti-Catholic. Trust me, you’ll want to read Snow’s entire essay.

Three years ago, writing in The Telegraph, Charles Moore penned these lines in an appreciative column about Mantel:

So why has she caught on? Why has such genuine merit and uncuddly, almost cold dedication to her art been recognised in a culture obsessed with celebrity?

I am not sure of the answer, but I suspect it has something to do with her sense of the nearness of anarchy and darkness. She seems to fear those things and to be attracted to them. As a Catholic, she has a strong sense of the reality of evil, but as a non-believing one, she cannot find the redemption. This is a good position from which to convey horror.

One of her early novels is called Vacant Possession. It is about a deranged woman who pretends to be a cleaner in order to take revenge on the occupants of her former home. The book’s title obviously refers to the familiar legal term, but it is also Mantel’s nod to Milton who, in Paradise Lost, says that “the fiend” may “invade vacant possession” and “some new trouble raise”.

The fiend is often present in her work, the troubling something at the corner of one’s vision. In her as yet unfinished trilogy, Thomas Cromwell carries some shadow in his life which cannot be spoken of.

English literature excels at these experiences on the borders of consciousness, at madness or anarchy imagined with the clarity of a sane mind. Now that she has turned one of the darkest passages in our history into a great work of fiction, Hilary Mantel can be said to have captured the national imagination.

“Vacant Possession.” Hmm.

By the grace of God I have never had an experience like Mantel’s, though I did go through a difficult period in the summer of 1990 or ’91 in which I became aware of a presence in my apartment as I slept. It got so bad that even though I wasn’t much of a Christian, I took to sleeping with a crucifix in my hand, as if I were a child with a teddy bear. I think back on it now and shake my head over how crazy that was. I am certain that there was a presence there, and that it was a malign presence. It would show up in my dreams sometimes, and communicate that it wanted me. Unlike most nightmares, these felt as if they were messages, invitations.

What’s crazy to me now is how hard I worked to assure myself that everything was normal, that I was just going through a rough patch, and that there was nothing out of the ordinary for a man in his mid-twenties to have to sleep at night with a crucifix in his hand to ward off the night terrors.

The only thing that made it stop was my leaving that apartment. What made me leave? Mostly, it was the night I sat straight up in bed out of a deep sleep because I sensed the presence of someone in the room, watching me. I would not have been surprised to have seen a burglar standing over my bed. What I saw was a creature. I can see it in my mind now as clearly as if I had looked at the thing last night. It chills me today to think of it, and I won’t describe the thing to you. I was furious at it, and leapt out of bed at it. I saw it run, then disappear.

You had a nightmare, I tried to tell myself. But this was no nightmare. Something had happened.

Here’s the thing: I had been dabbling with the thought of becoming a Catholic at that time, but refused to commit to the path of conversion — chiefly because I knew that it would disrupt the casually hedonistic life I had been living. That experience in the apartment — not just seeing the entity, but the whole matter of the creeping awareness that something wicked shared that space with me — drove me towards the Church, even against my will. It helped convince me that there was another dimension to our life, one that remains hidden to us in the everyday, but that may manifest at times beyond our control. I suppose you might say that even in my most agnostic period, I always supposed that if there was a God, then he was like the kindly owner of an estate, the Duke you never saw, but in whose authority you trusted to order the grounds on which you lived. To put it another way, my late-20th century, Moralistic Therapeutic Deist cosmology had no room in it for demons.

But now I had seen one. It had been invading my dream life for months, communicating to me that it wanted to enter into me. God, I had a chill writing that sentence just now, thinking about how stupid I was back then, wondering what would have happened had I not awakened suddenly and seen the entity made manifest at the foot of my bed. After that night, I could not deny that something was very wrong, and that it wasn’t simply in my head.

I couldn’t live in that apartment anymore, not with that thing. I moved. That ended the night visits. And before much longer, I began to take instruction in the Catholic faith. On my first meeting with the priest who began my catechesis, I told him about the events in my apartment in those months. He was an old man, and Irishman who was part of a religious order. He took me seriously, and told of being sent to Africa as a newly ordained priest. The things that missionary priests in Africa encounter on a nearly daily basis, he explained, are entirely alien to the Western experience in modernity. But they are real. You cannot spend any time in Africa doing missionary work and not come hard up against the reality of the demonic, he explained.

The old priest did not believe that malign spirits only dwelled in Africa, of course. We have them here too, but we have educated ourselves out of knowing what we’re dealing with when we see it. And in turn, we fail to turn to the Church for help when we are besieged.

Reading Patricia Snow’s essay and Charles Moore’s column made me reflect on how events in my own life have affected my stance towards the world as a writer. Mantel is an artist and I am not, but I share with her a sense of the nearness of anarchy and darkness. I, of course, do find hope, shelter, and redemption in the Christian faith, as she does not. Yet I see recurrent themes in my writing emerging from my most formative experiences.

- The world is not what we think it is. What is unseen is as real as what’s seen.

- People are not who we think they are; they are not even who they think they are.

- People will go to extraordinary lengths — including telling themselves outlandish lies, accepting what ought to be unacceptable and making their own lives and the lives of others miserable — to avoid facing truths that would compromise the worldview upon which they’ve settled.

- The battle lines between good and evil, and between order and chaos, are not drawn where we would like them to be. The front is everywhere, most particularly within our own hearts.

- Be wary of the treachery of the good man who believes in his own goodness.

- “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.” (Ephesians 6:12)

This painting below, “Carnival Evening” by Henri Rousseau, hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. A print of it also hangs on my wall. From the moment I saw it, I was mesmerized by it. This is as close as I’ve ever seen to my view of the human condition (absent the reality of God and Jesus Christ) captured in a single painting. As I wrote in this space on the day I saw it:

This scene symbolizes the way I move through life: as a partygoer who finds himself … feeling very much out of place, on the way home, in the deep wintry woods under a full moon, with all the beauty and the danger and the mystery therein. Interesting to think about how art doesn’t explain, but reveals.

I like to think that unlike the man and woman in the painting, I am aware of the Watcher in the Dark, which is why I clutch the crucifix in my heart, and do my best to stand against the darkness, clothed in carnival clothes, but never forgetting that beyond the carnival is the dark wood. On the other hand, after closer examination, I believe Rousseau has captured the couple at the moment they have become aware that they are being watched. Look at them closely: they are not walking — his arms indicate forward motion, but his feet are planted firmly — nor are they looking behind themselves. They are frozen in place. After reading Patricia Snow’s essay on Hilary Mantel, I wonder if she was a frightened child staggering through the dark wood, saw the Watcher, and yielded to his malign designs on her.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.