The Grateful Acre, The Prairie Of Pain

Reader Ellen Vandevort Wolf went to see Will Arbery’s play Heroes Of The Fourth Turning, and sent me this letter about it (if you don’t know what the play is about, read the first thing I wrote about it):

I wasn’t able to comment in your post about the play but after seeing the matinee yesterday, I just had to write.

In NYMag, Sarah Holdren starts her review this way: “Will Arbery’s Heroes of the Fourth Turning is so frighteningly well written, it’s hard to write about. It’s the rare play where standing and picking up your shit and shuffling down steps and going outside—especially onto 42nd Street—immediately after feels like a kind of violence. You’re not ready for it yet. You’re still in Arbery’s world — murky yet lit by lightning, lyrical and scary, brave and terribly gentle. Coming out of the whole thing is like waking to a bucket of water thrown in your face. But even that jolt feels right in its way, because Heroes is a kind of nightmare.”

With the exception of that last phrase, this was my reaction as well. What I really wanted to do was stay in my seat and sob to the depths of my being. I’m still trying to articulate what it meant to sit there for two hours, in which most of the time I was oh so uncomfortable, hearing conservative arguments I’m well acquainted with but which very few of my fellow New Yorkers have ever heard, afraid of how the audience would respond. While I was uncomfortable, the woman sitting next to me seemed viscerally angry. But gradually I found my head forgetting the characters’ political leanings and my heart breaking for these beautiful broken people as the play climaxes, when Arbery shatters the political zeitgeist and sends us careening into the supernatural, confusing, devastating pain of humanity where we all truly live. When the lights came up, everyone seemed shaken, including the girl next to me.

The trick Arbery used that kept everyone in their seats was his resistance to agitprop and his skill at creating five “deplorables” who are undeniably human. He left us at the end with no absolution for either side of the political spectrum. Every time one of his characters started to sound like the liberal caricature of a conservative, he inserted an insightful self-evaluation or a pointed challenge from another character to deny the audience any chance of feeling justified or superior. His most empathetic character, Emily, responds to Theresa’s rabid attack on pro-abortionists by insisting that one can still like pro-choice people. I was sure he’d make Emily pro-choice but he didn’t. It was genius. He would take a character just to the brink of a liberal’s comfort zone, but never hand any of the characters over to vilify. At the same time, he didn’t affirm or valorize any of the five characters’ conservative leanings. What he did was show fully-realized, particular, complicated conservatives, a very rare event for an American stage.

I’m not sure what Arbery really thinks of conservatives. He mentioned in an NYT article being angry at Trump’s victory and needing to write about what kind of person could possibly vote for him. He certainly sounds, at the very least, ambivalent. NYMag’s Holdren seems to think the play indicates that the conservative worldview is on its last breath, not worth saving, and that the generator’s scream doubles the characters over like “devils in torment, hearing the sound of their own sad, poisoned souls.” It’s telling, then, that the bar is so low that right-leaners will grab at any little crumb that comes their way from the entertainment world, even one that isn’t really, at its core, for them. It’s to his immense credit that he’s willing to run the risk of conservatives hailing him as their champion, even if he feels otherwise. And it’s to his immense talent, that if he is as ambivalent as he sounds, conservatives consider this a positive description. (Also, I said to my husband that only a Catholic could have written the ending with the supernatural surprises. How he touched down, just for a second, on that topic [regarding Kevin’s parting story and Justin’s “lie”] was superb story-telling. Emily’s unrelenting channeling was devastating.)

Arbery keeps the liberals in their seats because of his riveting, intelligent, funny dialogue, he keeps the conservatives there by reflecting back to them characters they–to some degree–recognize, and he keeps the rest of us there by giving voice to our longing that both sides would stop for a second and recognize that we’re all human, and that we deserve to be treated with the respect due for simply being human. I came to New York to work in theater and have seen countless excellent plays in my life. But I can count on one hand the number of times a production has reached a place so deep within me that I couldn’t breathe and sobbing seemed like the only response. I will not soon forget this play. Please thank Will Arbery from this New Yorker for counting all of us human.

Done.

I’ve been thinking more about that play, and its deeper meaning. I think the core meaning has to do with the Millennial generation’s haunting sense of dispossession. This is a generation that has been exiled from the givenness of life — even from the givenness of their own bodies (though there are no transgender characters, transgenderism as a form of alienation from physical givenness would very much fit the philosophical framework of the play). These characters are struggling to find a place for themselves — a place where they can hope — in a world that is beset by a malign spirit that no one can quite name.

On the front page of the script, Arbery features this quote from the poet Mary Ruefle:

And who among us is not neurotic, and has never complained that they are not understood? Why did you come here, to this place, if not in the hope of being understood, of being in some small way comprehended by your peers, and embraced by them in a fellowship of shared secrets? I don’t know about you, but I just want to be held.

That’s a key to the meaning of the drama. These are five lonely people who were once given to each other when they studied together at the Wyoming college, and who, because of that past, share something. They are all lonely — even Teresa, the successful Ann Coulter-like pundit, who is planning to be married. She’s a hard-right winger who lives in Brooklyn, and is fighting for a reactionary world, but is using that crusade as a way to hide from her own fears.

Kevin thinks too much. He’s passionate, but unsettled. Justin, the cowboy, is a partisan of the Benedict Option. He says it’s getting too hard to hold on to the Good, and advises staying away from the cities. Emily has been chronically ill — with Lyme disease, no doubt, as this character was based on Will Arbery’s sister Monica, who has suffered from it for years — and her illness defines her experience. She takes Flannery O’Connor as her spiritual guide, and offers her pain as a sacrifice through which she hopes to obtain grace.

The more I think about the play, the more I realize that it’s really about particularity, place, and givenness in a world of suffering. Though Will Arbery has said that he no longer practices the Catholic faith in which he was raised, this is a profoundly Catholic play. These characters are all adrift in liquid modernity, which obliterates these things in favor of choice, and they’re trying to come to terms with the fact that they cannot escape their particularity. Teresa, the Ann Coulter figure, says to Kevin:

We’re allowed to read Protestants idiot, Dr. Jim gave me the book okay?, he thought I could handle it, LISTEN, Breuggemann said that every single revelation in the Bible is evidence of the scandal of the particular. The scandal of this particular person getting this particular revelation. This carpenter, this shepherd, this stutterer, this virgin. And grace – grace always accompanying the grotesque. Sometimes the moments that are the most grotesque are the closest to transcendent grace.

She goes on:

Actually this is at the heart of my writing right now. The nation as the last bastion of the particular. The kingdom is the kingdom and the kingdom has particular laws. The lepers need to be healed, not championed for their leprosy. We’re not meant to structure our society according to every freakish chosen “right.” We’re supposed to strive for the good. The particular, written, incarnate, natural Christian good. Otherwise, what are we? A throbbing mass of genderless narcissists. There’s no “thisness” in the liberal future. There’s no there there. It’s empty. What’s really radical is sacrifice. Painful particularity is what we need. Otherwise we’re culturally lobotomized. We’ll be force-fed brand new oppressed identities every year and we’ll bow to the tyranny of rights. Fuck rights. Europe right now has no idea what to do with Islam. It’s going to eat them alive because it’s so fucking specific and there’s a power there. We need to embrace our American identity as a representative of Christ on the globe. Because it’s Christianity alone that has a God who knows what it is to be a man, who sacrificed his life as a man, who felt the full pain of our particular human journey into death. And we need to be ready to sacrifice ourselves the way he sacrificed himself for all of us. What a scandal! What a scandal that we would rather put up a wall, that we would rather die, than be subsumed by an invading disease.

Some of that sounds good, but then you realize that she has turned her appreciation for particularity into a worship of nationalism and right-wing politics. And you also realize, the more you go into the play, that she has thrown herself into the life she has not as an embrace of particularity, but as a form of escape. That line — “What a scandal that we would rather put up a wall, that we would rather die, than be subsumed by an invading disease” — is turned on her rather brilliantly in a confrontation at the play’s end.

I can imagine liberal New Yorkers sitting there hearing Teresa say these words, and thinking of her as a simplistic villain. But she’s not. I know Christian conservatives who think just like her. They’re not villainous, or if they are, there’s nothing simple about them. As St. Augustine would say, their sin is a perversion of the Good. Teresa has taken the truths that she was given, energized them with rage from her own suffering, and made of them a shield to protect herself from having to come to terms with her own demons — as we see later in the play.

After Teresa delivers this angry lecture to Kevin, he takes accurate measure of her:

Yes, it’s just

I got sad

If you’re all about the particular, and ordinary people Then why don’t you want to hear about all my things, My particular things

There you have the first intimation that Teresa is lying to herself — and lying to herself in a way that will be familiar to many of us. Especially us intellectual types who, in our particular lives, profess abstractions but live differently, and dwell within the cognitive dissonance.

Justin, the cowboy, recites for the group the text of a children’s book he has written, called “The Grateful Acre.” I’m not going to reproduce it here, because it really is a special moment in the play — special, but also eerie. It brings to mind Shel Silverstein’s “The Giving Tree,” but in this case, it’s a fable about an acre of land that endures cycles of life, death, and suffering, with a spirit of gratitude for whatever happens to it. That description might sound corny, but I assure you the text is not. It is a children’s fable instructing the reader about the kind of fundamental stance toward life that they should have.

Later, though, in a discussion with chronically ill Emily, she describes her body as a “prairie of pain.” The passage is here:

JUSTIN

Your dad was saying and I thought it was brilliant that it’s this Cartesian “neo-Gnosticism” that convinces people that their souls are somehow separate from their bodies, and their bodies can somehow be fashioned however they like.EMILY

Oh that’s beautiful J, that’s so — my body is so much a part of me I can’t even begin And I didn’t choose this, my body is just a friggin

prairie of pain,

and I can’t choose to make it go away

It’s just what I’ve been given.

The grateful acre is the prairie of pain. Catholicism is about accepting the suffering, as Christ did, and allowing it to refine you, to make you holy.

Emily has been given to know the prairie of pain in a particular (that word) way, but all four of these friends are suffering. They have been schooled in how to think about the world, but the encounter with suffering has tested, and is testing, their ideals. Emily is the only one whose suffering — whose given suffering — has left her without a choice in how to meet it. It has made her radically empathetic … but, as we learn, it has also made it difficult for her to discern moral truth.

In his New Yorker review of the play, Vinson Cunningham writes:

Justin never quite forgets that blood on the patio, or the difficulty he had killing the animal. That’s never happened before—hunting is a favorite pastime—and he sees the change in himself as just one more sign of the times’ palsying effect on the simplicity of the old ways.

But nothing in this richly allusive play is exactly as it seems at first glance. Justin’s fixation on the early sacrifice—he keeps trying to scrub away the blood when he thinks nobody’s watching—put me in mind of Cain, fretting over the spilled blood of his innocent brother, Abel.

The play begins with Justin killing a deer. Symbolically, this seems to say that violence and suffering are givens of the human condition, and that we are not going to be able to escape them. We are not going to be able to create the perfect conditions for ourselves; all our grateful acres will inevitably turn into prairies of pain, because that’s what it means to live. How we inhabit that ground, and whether we make it holy or desecrate it, determines the character of our lives.

Teresa has gone to New York and fashioned herself as a Millennial Joan of Arc of the media, but she is hiding from her own fears. Kevin keeps waiting for something to happen to tell him what to do with his life, while time passes (Teresa is not wrong to say that his is a failure of courage.) Justin has become a contemplative, and, as we see in the play’s final moments, has chosen a way to deal with his own rage at the darkness overtaking the world — but is it the right way? Emily has no choice but to dwell in the prairie of pain.

Without giving away too much, I can say that Professor Gina, who taught all of them (and who is based on Will Arbery’s mother Ginny), shows up to sort her pupils out. There is conflict, but the main thing I took away from her appearance is that for all her flaws, she was willing to suffer for the sake of creating life, and teaching, and reaching out, in her own broken ways, to love the students God sent to her, and to give them what they needed to thrive. Prof. Gina has created a way of life out of her own historical givenness — she was a Goldwater girl back in the day — but her daughter Emily, and Emily’s friends, can’t follow her as closely as she would like, because the historical conditions into which they’ve been thrown are so different. The thing they have most in common, though — this, according to Emily, is that they all suffer. Emily talks about all the physical illness her mother has suffered:

… she’s walking around in tremendous pain every freaking day. And she never complains. That’s some faith. That’s some faith. So y’all I guess we can forgive her for being a little intense.

The grateful acre, the prairie of pain. The human stain that stays with us. I’ll leave you with these lines from Ellen Wolf:

But gradually I found my head forgetting the characters’ political leanings and my heart breaking for these beautiful broken people as the play climaxes, when Arbery shatters the political zeitgeist and sends us careening into the supernatural, confusing, devastating pain of humanity where we all truly live. When the lights came up, everyone seemed shaken, including the girl next to me.

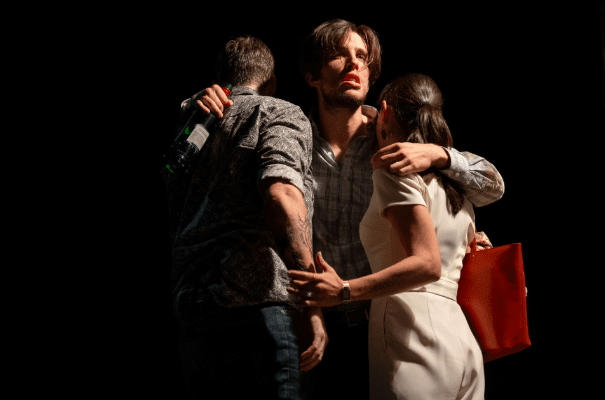

Yep. It’s that kind of play. Here’s the trailer:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EO3Bn_PNQPc&w=525&h=300]

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.