Evangelicals’ Trump Shield

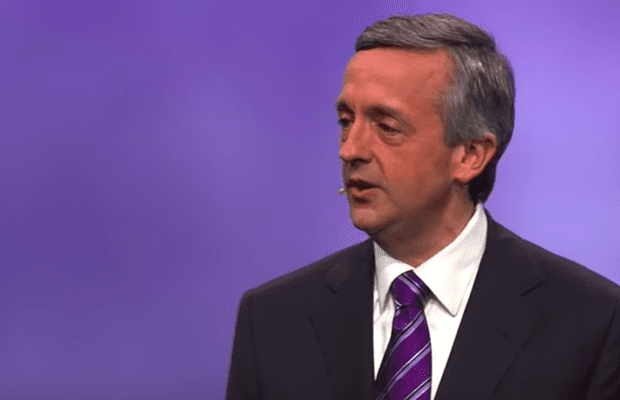

Elizabeth Bruenig spent some time recently down in Texas, talking to Evangelicals about whether or not they’re going to support Donald Trump in 2020. Her Washington Post story is full of nuance, and well worth reading. There’s something in it about Robert Jeffress, the pastor of First Baptist Dallas, that is important. He’s the Trumpiest of all the pro-Trump Evangelicals, but his take on the Trump phenomenon is darker (and, by my lights, more accurate) than you might think:

Could it take a decidedly worldly man to reverse the fortunes of evangelicals who feel, for whatever host of reasons — social, racial, spiritual, political — that their earthly prospects have significantly dimmed?

Jeffress didn’t think so, but not for the reasons I would have guessed. “As a Christian, I believe that regardless of what happens in Washington, D.C., that the general trajectory of evangelicalism is going to be downward until Christ returns,” he explained. “If you read the scripture, it’s not: Things get better and better and more evangelical-friendly or Christian-friendly; it is, they get worse and more hostile as the culture does. … I think most Christians I know see the election of Donald Trump as maybe a respite, a pause in that. Perhaps to give Christians the ability and freedom more to share the gospel of Christ with people before the ultimate end occurs and the Lord returns.”

It was strange to think of Trump as a bulwark against precipitous moral decline. After all, he appears to have presided over a more rapid coarsening of news and discourse than the average candidate. Even if you count modern history as a story of dissolution and degeneracy, few, if any, other world leaders have launched as many headlines containing censored versions of the word pussy.

But Jeffress didn’t see Trump pausing the disintegration of evangelical fortunes by way of personal virtue — or even cultural transformation. He spoke instead of “accommodation,” perhaps alluding to the kind of protections announced only a few weeks after our talk by Trump’s Department of Health and Human Services, which safeguards the jobs of health-care workers who object to participating in certain procedures for religious reasons. Rather than renewing a culture in peril, in other words, Jeffress seemed to view Trump as someone who might carve out a temporary, provisional space for evangelicals to manage their affairs.

I really did believe that Pastor Jeffress believed in Trump earnestly, in that conventional Evangelical “Take America Back For Jesus” way. After all, it was his church’s choir that performed that “Make America Great Again” song that its choir director wrote the choir director of Second Baptist Church in Houston wrote. When I spoke with him last fall in LaGuardia Airport, he hinted strongly that his view of Trump and the Christian churches’ future was more pessimistic than people think, but that conversation was not on the record, so I didn’t write about it. Now he’s said it on the record to Liz Bruenig.

What a remarkable thing it is for a Southern Baptist pastor of his stature to take such a bearish stance on America’s future. I sent him a copy of The Benedict Option after we met. If Pastor Jeffress really is that pessimistic about the church in post-Trump America, I hope he will read it and start preparing the people in his congregation for hard times in the near future.

As I’ve maintained all along, the best reason for Christians to vote for a barbarian like Donald Trump is that his administration grants us time and space to prepare for what’s to come. It sounds like Jeffress has come to pretty much the same conclusion as I do in The Benedict Option: that taking the longer view, this post-Christian culture is not likely to be turned around, and that if the faithful can read the signs of the times, they will embrace ways of living that build resilience and resistance into themselves, their families, and their churches.

Judging by his comments to Bruenig, Jeffress does not believe that Trump (or anybody) is going to Make America Great Again. Rather, he’s become very pessimistic about the future, and believes that Trump at best is only going to forestall the inevitable. I don’t want to read too much into what he told Bruenig, but I think this is true.

Bruenig didn’t only talk to pro-Trump Evangelicals, let me be clear. What I found refreshing about her piece, particularly given her own politics (she’s a progressive Catholic) is that she allows for the possibility that Evangelicals who take the despairing pro-Trump line are … right. Right in the sense that they correctly see what the future looks like for people like them.

More from her piece:

As to the cultural facts on the ground, Jeffress might have something of a point: Overall, American culture is hardly trending toward adherence to evangelical beliefs, with approval of same-sex marriage steadily rising among all religious groups (even evangelicals), religious affiliation quickly dropping, and support for legal abortion lingering at all-time highs. Jeffress is hardly alone in believing that evangelicals need some sort of special accommodations from a society that doesn’t share their values and that they feel persecuted by; according to a Pew Research Center survey released this year, roughly 50 percent of Americans believe evangelicals face some or a lot of discrimination, including about a third of Democrat-leaning respondents. If the rhetoric of spiritual renewal that at times illuminated the Bush presidency has ultimately faded, it makes sense that a figure such as Trump should inherit its dimming twilight and all the anger, despair and darkness that dashed dreams entail.

And:

Which raises a series of imponderables: Is there a way to reverse hostilities between the two cultures in a way that might provoke a truce? It is hard to see. Is it even possible to return to a style of evangelical politics that favored “family values” candidates and a Billy Graham-like engagement with the world, all with an eye toward revival and persuasion? It is hard to imagine.

Or was a truly evangelical politics — with an eye toward cultural transformation — less effective than the defensive evangelical politics of today, which seems focused on achieving protective accommodations against a broader, more liberal national culture? Was the former always destined to collapse into the latter? And will the evangelical politics of the post-Bush era continue to favor the rise of figures such as Trump, who are willing to dispense with any hint of personal Christian virtue while promising to pause the decline of evangelical fortunes — whatever it takes? And if hostilities can’t be reduced and a detente can’t be reached, are the evangelicals who foretell the apocalypse really wrong?

Read the whole thing. It’s really worthwhile.

In a post I wrote a few months back, titled “Trump the Katechon” (katechon here means “the force that holds back chaos and disaster”), I explored the idea that Jeffress seems to endorse: that the meaning of Trump is that he is delaying the small-a apocalypse for conservative Christians. In the piece, I talk about how blind many progressives are to their own side’s hostility to social and religious conservatives, and how that blindness prevents them from understanding why people who think Trump is a bad man would vote for him anyway, solely out of self-protection. As a Trump-voting Christian lawyer I met recently said to me, “Donald Trump is going to embarrass me every day of the year, but unlike the other side, he doesn’t hate my faith, and seek to do me harm.”

In that post, I quoted the #NeverTrump Evangelical Erick Erickson, explaining why he has flipped, and will be voting for Trump in 2020:

We have a party that is increasingly hostile to religion and now applies religious tests to blocking judicial nominees. We have a party that believes children can be murdered at birth. We have a party that would set back the economic progress of this nation by generations through their environmental policies. We have a party that uses the issue of Russia opportunistically. We have a party that has weaponized race, gender, and other issues to divide us all while calling the President “divisive.” We have a party that is deeply, deeply hostile to large families, small businesses, strong work ethics, gun ownership, and traditional values. We have a party that is more and more openly anti-Semitic.

The Democrats have increasingly determined to let that hostility shape their public policy. They are adamant, with a religious fervor, that one must abandon one’s deeply held convictions and values as a form of penance to their secular gods.

On top of that, we have an American media that increasingly views itself not as a neutral observer, but as an anti-Trump operation. The daily litany of misreported and badly reported stories designed to paint this Administration in a negative light continues to amaze me. Juxtapose the contrast in national reporting on the President and race or Brett Kavanaugh and old allegations with the media dancing around the issues in Virginia. Or compare and contrast the media’s coverage of the New York and Virginia abortion laws with their coverage of this President continuing the policies of the Obama Administration at the border, including the Obama policy of separating children from adults. Or look now at how the media is scrambling to cover for and make excuses for the Democrats’ “Green New Deal,” going so far as to suggest that maybe, just maybe, the outline of policy initiatives was an error or forged.

One does not have to pretend that Donald Trump is a good man in order to conclude that whatever his sins and failings, he is less of a danger to the things that matter most to conservatives than any conceivable Democrat. To be sure, there will be some conservative Christians who use the same rationale to vote for the Democratic candidate — that is, concluding that no matter how bad the Democrat is in important ways, Trump is worse, and should be turned out of office.

Hey, I understand that reasoning! I really do. What I don’t get is why it’s so easy for people to understand why, say, black Americans vote in defense of their perceived interests, or Latinos do, or gay people do, and so forth … but it is considered appalling when white Evangelicals vote in defense of theirs.

I have decided that I can’t do what I did in 2016, and stay on the sidelines, even though my vote doesn’t really count in a solid red state like Louisiana. If I end up voting against Trump, it will be because I have judged him even worse than the Democrats. If I end up voting for Trump, it will be because I have judged the Democrats as even worse. Either way, it will be a vote from despair. I wish it were otherwise, but rose-colored glasses get in the way of seeing things as they actually are.

Some friends of mine argue that conservative Christian support of Trump is going to make the inevitable backlash that much worse. They might be right. I expect it to be bad, for sure. If my friends are wrong, they’re wrong only because the anti-Christian sentiments and policies from the Left were going to be harsh even if we’d elected a conventional Republican president. Anyway, read Liz Bruenig’s piece. One way or another, the next decade is going to be very difficult for Evangelical Christians, both internally and externally. And not just for Evangelicals…

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.