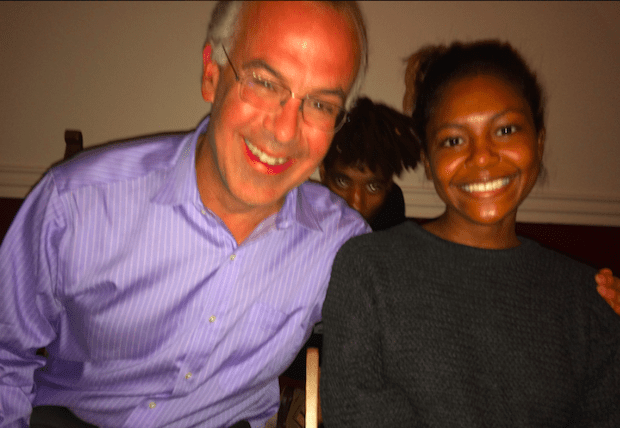

Politics At the Dinner Table

The kids who show up at Kathy and David’s have endured the ordeals of modern poverty: homelessness, hunger, abuse, sexual assault. Almost all have seen death firsthand — to a sibling, friend or parent.

It’s anomalous for them to have a bed at home. One 21-year-old woman came to dinner last week and said this was the first time she’d been around a family table since she was 11.

And yet by some miracle, hostile soil has produced charismatic flowers. Thursday dinner is the big social occasion of the week. Kids come from around the city. Spicy chicken and black rice are served. Cellphones are banned (“Be in the now,” Kathy says).

The kids call Kathy and David “Momma” and “Dad,” are unfailingly polite, clear the dishes, turn toward one another’s love like plants toward the sun and burst with big glowing personalities. Birthdays and graduations are celebrated. Songs are performed.

I started going to dinner there about two years ago, hungry for something beyond food. Each meal we go around the table, and everybody has to say something nobody else knows about them.

Each meal we demonstrate our commitment to care for one another. I took my daughter once and on the way out she said, “That’s the warmest place I can ever imagine.”

More:

Bill Milliken, a veteran youth activist, is often asked which programs turn around kids’ lives. “I still haven’t seen one program change one kid’s life,” he says. “What changes people is relationships. Somebody willing to walk through the shadow of the valley of adolescence with them.”

Souls are not saved in bundles. Love is the necessary force.

The problems facing this country are deeper than the labor participation rate and ISIS. It’s a crisis of solidarity, a crisis of segmentation, spiritual degradation and intimacy.

Read the whole thing. It will give you a lift amid all the awful news from the campaign trail. And to learn more about AOKDC, the nonprofit organization Kathy and David started to help support and expand their work with these kids, go to this page. It’s amazing what they do. And all it took was a willingness to do it, and to keep doing it. No big plans, just acting.

See, this is the kind of thing I mean when I talk about the Benedict Option: things like what Kathy and David are doing. They obviously don’t need a theory (“the Benedict Option™”) to do this stuff. But it is an example of politics that aren’t politics as we customarily think of it. From the manuscript of The Benedict Option:

What kind of politics should we pursue in the Benedict Option? If we broaden our political vision to include culture, we find that opportunities for action and service are boundless. Christian philosopher Scott Moore says that we err when we speak of politics as mere statecraft.

“Politics is about how we order our lives together in the polis, whether that is a city, community or even a family,” writes Moore. “It is about how we live together, how we recognize and preserve that which is most important, how we cultivate friendships and educate our children, how we learn to think and talk about what kind of life really is the good life.”

That’s it, right there. This is what Vaclav Havel called “antipolitical politics,” a concept he developed out of the experience of powerlessness Czech dissidents felt under communism. They could do nothing in the realm of politics per se — so Havel and his circles began to think of “politics” in the sense that Scott Moore mentions. If they could do nothing about changing the communist system, at least they could do whatever they could, in community, to keep the communist system from changing them. Again, a passage from The Benedict Option:

“A better system will not automatically ensure a better life,” Havel goes on. “In fact the opposite is true: only by creating a better life can a better system be developed.” [Emphasis mine.]

The answer, then, is to create and support “parallel structures” in which the truth can be lived in community. Isn’t this a form of escapism, a retreat into a ghetto? Not at all, says Havel; a countercultural community that abdicated its responsibility to reach out to help others would end up being a “more sophisticated version of ‘living within a lie.’”

Obviously we conservative Christians aren’t living under totalitarianism, and we still retain the ability to act in customary political ways — and we should. But we are much less powerful in that sense than we used to be, and our weakness is going to get much worse in  the near future, no matter which candidate wins in November. Because we lost the culture war, we have lost the political war, and that’s something we have to accept.

the near future, no matter which candidate wins in November. Because we lost the culture war, we have lost the political war, and that’s something we have to accept.

But that does not mean we give up! It means we keep fighting politically, but in a different way. If we ever want a better political system (meaning one in which the laws and practices of our democracy are more reflective of truth and justice), we have to create better lives — that is, we have to create communities that embrace practices that cultivate Christian virtues, and increase caritas within us.

I’m strongly convinced that the most important fight for American Christians now in the realm of conventional politics is the one for religious liberty. We have to preserve as much as we can the private spaces within which to build these communities. But come what may on that front, we still have to do it. If the Czechs did these things under communist totalitarianism, what right do we have to give up under post-Christian liberal democracy?

The long-term hope I have is that Ben Op communities — churches, Christian schools, and the like — will serve a role akin to monasteries of the early Middle Ages: beacons of light in a darkening time. I don’t know if Kathy and David, the couple in David Brooks’s piece, are Christians, much less if they are conservatives. But what they’re doing by establishing their home as a refuge for kids walking around wounded from the disorders of our time and place, and making a community from them, is a form of antipolitical politics. It pushes back hard against the forces of alienation, isolation, and atomization that characterize our culture.

There are hard limits to what orthodox Christians can do through politics in the public square, but many fewer limits to what one can do in the realm of antipolitics. At this point, the greatest limit is our creativity and willingness to try. And here’s the thing: if orthodox Christians don’t start doing things like this for ourselves, for our own kids, and for others, we aren’t going to make it. We can’t stop the pulverizing wave of post-Christian modernity, but we can hope to ride it out intact. And if we build communities, even ones as small as Kathy’s and David’s, that serve as refuges of love for those stranded and searching in the present Dark Age, then we Christians will attract all kinds of people who want the peace that we have. That’s how the early church did it, right?

And if we don’t establish communities like this, we may lose our peace, or never find it to begin with. We will sit around perpetually anxious as the remains of Christian civilization fall down around us. Trust me, I know from being anxious about this stuff!

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.